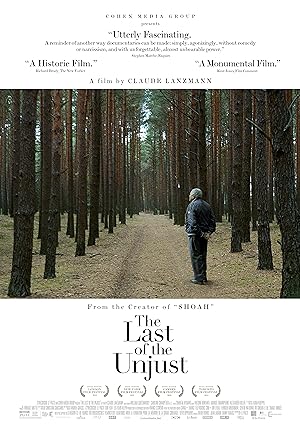

The Last of the Unjust was directed by Claude Lanzmann, the director of Shoah. Unlike Shoah, it focuses on one controversial Holocaust survivor’s testimony and is only over three hours long. Rabbi Benjamin Murmelstein was the only surviving Jewish elder, resided in a “model” concentration camp, Theresienstadt, and was briefly arrested for collaborating with the Nazis, but was later exonerated. The Last of the Unjust has two points: to indict Theresienstadt and vindicate Murmelstein. Nazis used this camp to show other countries such as Denmark and organizations such as the Red Cross that people were not being abused. Of course, even in a camp like that, the abuses were an integral part of the bureaucracy and daily life. Similar to Shoah, Lanzmann uses contemporary shots of the location to contrast the horrific testimony. It is chilling to see that the same rails are used for commuter trains today. The same nightclub is still standing. The camp is just a bucolic, mostly empty field with a single dilapidated structure. Lanzmann occasionally uses drawings by victims who did not survive and clips from Nazi propaganda films about the camp. I did bristle at Lanzmann constantly trying to rationalize why Murmelstein survived, and others didn’t: he had a story to tell; he was the smartest, etc. Lanzmann unintentionally implies that those who didn’t survive weren’t the smartest or didn’t have a story to tell and clearly loves Murmelstein whereas Murmelstein seems uneasy at Lanzmann’s attempts at physical consoling and would prefer to just talk. What makes someone the smartest-what standard are we using? If some transcendentally evil gigantic thresher machine sweeps over Europe, survival may depend on any number of factors largely dependent on the perpetrator and not the victim. Occasionally Lanzmann would narrate the film, share his feelings or read an excerpt from a historical document or Murmelstein’s book. Lanzmann’s insertion into The Last of the Unjust occasionally felt repetitive or confusing since the explanation did not precede his appearance. I think that Lanzmann unintentionally got in the way of Mumelstein’s story because he was so eager for the audience to love Mumelstein as much as Lanzmann does. Show. Don’t tell. In contrast, Mumelstein wanted people to know two things: the contrast between the Nazis’ use of words and their sinister meaning, and that Eichmann wasn’t some banal everyday man, but a demon. He was clearly angry at Eichmann’s trial and thinks that the trial should have been more damning. The Last of the Unjust is not an easy movie to watch. The Last of the Unjust is a movie fraught with the contrasting agendas of the interviewer and his subject, but even with its imperfections, it is a story that must be told. If all the film in the world was used to shed light on the Holocaust, there would still be stories left untold