This review was originally published on Roarfeminist.org

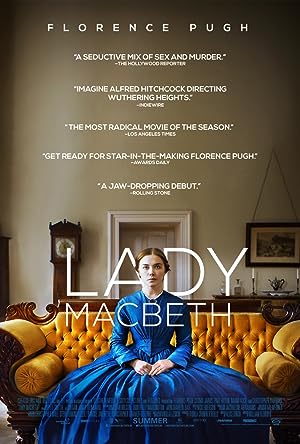

Lady Macbeth may be a perfect film. It has nothing to do with Shakespeare (you are thinking of Macbeth). It is an adaptation of Nikolai Leskov’s novel, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. Alice Birch wrote and William Oldroyd, a veteran theater and first feature film director, directed it. In a time when Sofia Coppola is desperately and ahistorically cutting out one black character from her film adaptation of The Beguiled because she did not want to cause offense, Lady Macbeth eagerly jumps into the deep end, sets the adaptation in nineteenth century rural England and embraces the nuances of class, gender and race of that period.

Lady Macbeth is a period piece, but it is far from the genteel world that most costume dramas fetishize. The film begins abruptly, and the viewer knows less than the (anti-)heroine, Katherine, a young woman, about what is unfolding. The viewer initially relates to Katherine because just like her, our questions and concerns are not germane and never answered outright. Like her, we have to discover this world for ourselves. She is treated like a new addition to the home, but less useful than furniture, and any interaction is terse, begrudging and disapproving so any idea that she may have anything to say is shut down by those that matter. We relate to her frustration and confinement.

The film owes a debt of gratitude to Chantal Ackerman for using the rhythms of daily life to repeatedly unfold and force the viewer to closely scrutinize and observe the people and their surroundings on screen for any changes instead of being spoon fed dialogue. You will not understand until close to the end of the movie why Katherine’s husband is such a bastard. Oldroyd starts with close ups of Katherine then in successive scenes, he broadens the scope of the camera to provide context. Even though the pacing is deliberate, Oldroyd always keeps his audience off balance by giving his audience slightly more information in every moment so we have to reevaluate our prior impressions. No detail is extraneous, and you must be alert and give the film your rapt attention.

An American could never make Lady Macbeth. We begrudgingly have some grasp of the effects of race and gender in society though we are constantly trying to erase it instead of address it (Sofia!), but class is simply elusive to us. Americans are also not textured in the way that these three factors play out in different contexts. The movie never falls into a binary way of thinking, but is constantly demanding that we ask who does society have in control at this moment, can the one with the disadvantage play some mental judo to gain the upper hand and by gaining the upper hand, in what ways have society’s rules been enforced and/or subverted by the disadvantaged?

I do not want to give away anything away about the major events in the film because it is a great story, but I do want to give an example of what I mean about the constant shifting power dynamics that occur. The servants on the estate are women and men, black, mixed and white. In one scene, the male servants are having fun at the expense of a female servant’s dignity. At this moment, gender is more important than race: men have the advantage. Katherine enters the room. Class has the advantage. One of the men tries to reassert his dominance, but it is clearly a transgressive act, and the other men do not join in. Later on, the male servants, who were clearly buddies regardless of race in that earlier scene, become further segmented. There are two white men in a scene punishing the transgressing servant, but one is the owner of the estate, and one is the servant, who is clearly uncomfortable, but doing nothing to protect his colleague. Lady Macbeth acknowledges that yes, being male and white usually trumps all other factors, and being black and female means that you are privy to more intimate information about every part of society, but have no power to act and will be the scapegoat, but look closer for the joker because the joker can take many forms at different times.

This film will make some viewers uncomfortable. It depicts the world as so broken that solidarity in unhappiness and creating any natural bonds of affection are impossible even when the other person has done nothing to harm you because the primary concern is survival. I love when films keep me off balance, and I cannot completely root for one person. It prevents viewers from having guilt-free vengeance in the fantasy of a movie theater and forces us to ask ourselves about what we wish that we could do, what we actually would do and what we should do. One person never has the complete story, and even as the viewer, we are not omniscient. We make decisions with flawed intelligence and selfish motives. Noble goals are theoretical and hide baser ones. If someone shows concern for you, this film suggests that you should be a little suspicious.

When the roles were cast, Oldroyd said that they were awarded to the best actors regardless of race, which resulted in roles for black actors. The British Film Academy of Film and Television Arts has criteria to encourage representation of minorities and the socially disadvantaged in British films. Lady Macbeth would not have been as multi-dimensionally superb as it was if this casting was uniformly one race. It is also a historically accurate depiction of the population during mid-nineteenth century Britain. Black people are not Athena, abruptly emerging fully formed today in Europe. They have been around since the beginning of time, yet filmmakers use claims of authenticity to excuse not casting actors of different races in certain roles. In cases when characters are of a different race, they make the actor white or cut the character out altogether for fear of possibly reinforcing stereotypes. Movies are machines that create empathy, and Oldroyd proved that other filmmakers are too lazy to look beyond themselves and not capable of being excellent and handling rigorous materials. Whereas American directors find race too challenging, Oldroyd sees it as an opportunity to create a richer world for his characters to inhabit.

I adored Lady Macbeth and would highly recommend that you see it in the theaters as soon as possible. If we don’t spend our dollars in the theater to support excellent film, we may not get any great movies in the future because they will be derided as not marketable. There is nudity and sexual content, but it is not prurient and valid given the context. There is violence, but it is not gratuitous. The most brutal murder happens to an animal, but if I could handle it and generally that would have me sobbing in the aisles in a fetal position, I would say that anyone could handle it. I jokingly call it the prequel to Get Out, but only in the most loving and admiring way. If this is Oldroyd’s first film, I’m excited for what else he has up his sleeve.