This review was originally published on Roarfeminist.org

“Look at everything always as though you were seeing it either for the first or last time: Thus is your time on earth filled with glory.” -Betty Smith

Greta Gerwig is an artist with a depth of feeling. She takes the prosaic and infuses it with nostalgia and an understanding of the mortality of moments, relationships and self. Her movies improve with and demand repeat consideration. Initially her films pass over you like a life unfolding, taken for granted, perhaps sniffed at for its quotidian nature and the ridiculous amount of attention and care devoted to, for example, going to an ATM or buying a cup of coffee. It is only after moments pass that you realize the impact of what she has captured, which seems like nothing at the time, but are retrospectively an American masterpiece and an emotional grenade that obliterates cynicism and evokes past emotions.

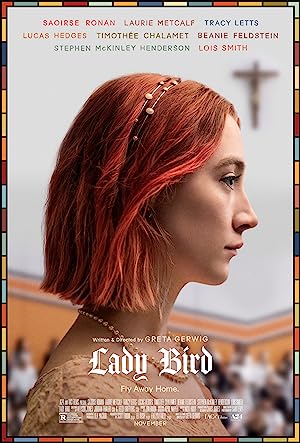

Lady Bird may be Gerwig’s first directorial debut, but she was Zelda to Noah Baumbach’s F. Scott Fitzgerald. She was the star and the writer behind some of his best works: Frances Ha and Mistress America. This film cements Gerwig’s entry at the pinnacle of mumblecore cinema, which feature naturalistic or improvised performances. Even though she is a success by all standards, she nurtures her memories of the past instead of forgetting her less than glorious moments: her imperfections, her failures, her outbursts, her exaggerations, her lies to herself, her neediness. We love her because we recognize ourselves in those moments that we try to forget and take courage that they do not need to be erased to move forward. Because her first film is about a girl during her senior year, 2002-2003, in a Sacramento single sex Catholic high school, Gerwig sadly cannot star in her film so Saoirse Ronan, one of the best actors of her generation, plays the titular character, who may resemble her creator.

Lady Bird begins in bed, but for Gerwig, intimacy comes not with sex, but whom you can fall asleep with. In Lady Bird’s case, it is her mother, but their waking moments are filled with the threat of pressing buttons and hitting nerves, which can quickly subside upon the sudden discovery of common ground, a pretty dress or a consolation. The mother, played by Laurie Metcalf, is desperate to make her daughter considerate and appreciate what she has because she may not get more, and the daughter wants more. Each sees the other’s desires as a rebuke and rejection, but understands that there is great love as evidenced by their unique ability to effortlessly psychologically wound the other.

Rent may be cheesy, but while watching Lady Bird, it helps to ask how do you measure a year: in friendships, boyfriends, school dances, after school activities, rituals, trips to the thrift store or supermarket, parties, holding a crying friend. Gerwig captures the mortifyingly selfish and glorious attempts at reinvention. I measured it in the instances that she was true to herself, stopped cultivating her image, showed that she cared about things even if no one else did and embraced being weird. These epiphanies are titanic albeit not shared. (I thought, “Not Dave Matthews. Nooooooo.”)

Lady Bird is also a generous film to its supporting cast and three-dimensional characters. Gerwig’s scenes begin before Lady Bird arrives in a scene and sometimes stay a minute after she leaves, which keeps the viewer cognizant that there are events unfolding, and the other characters are real people with stories just as poignant as hers that we do not know, but matter. Gerwig introduces us to Lady Bird’s brother, Miguel, a Goth Berkeley grad. In a moment of Lady Bird’s meanness, Miguel has an epiphany. At a cash register, mom and Miguel discuss the grocery bill with the employee discount while Lady Bird is oblivious to their financial situation because she just talked to a boy that she liked. Her parents find time to be alone and talk before Lady Bird interrupts their routine. You can also measure time in the way that Lady Bird begins to notice that they are people independent from her.

There are so many characters that deserve their own movies: her best friend who is even more special and gifted than Lady Bird realizes and possesses a quiet confidence to hold her own when challenged by her friend; the mournful priest who cares about the theater; the nun who has been married to Jesus for forty years, but knows Lady Bird better than she knows herself and has a sense of humor; the football coach priest who enthusiastically takes a role that he is ill suited for; or Shelly, Miguel’s quiet girlfriend who has a façade that is in opposition to her vulnerability. Gerwig depicts a casual diversity that Woody Allen needs to learn.

My favorite character may be the father who generously and selflessly supports his children, comforts his wife and infuses a sense of humor to any situation while quietly fighting professional and personal battles without a hint of effort. Hear him say, “Doritos,” and tell me that you don’t love him to. It is impossible.

Lady Bird is also clever at hitting archetypes then adding texture. It was not a surprise to me when it was revealed that a girl was sexually active and only cared about people based on their boyfriend, but casually it is mentioned that she is really good in school. She may be the typical rich kid neglected by her parents, but she is also a good kid who loves her community and has simple dreams. An adolescent boy thinks that he is deep and intellectual when he is really annoying, but he also may be devoted to school out of a sense of duty to the father that he loves. They may be people that we don’t want in Lady Bird’s life, but they are still people.

“Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home.” I don’t think that Gerwig ever reveals why her main character dubs herself Lady Bird, but I think that I understand. In her effort to become herself, she has to distance herself from the person that she thinks others want her to be, which means getting rid of your birth name if it doesn’t fit. It also means leaving home and embracing an identity as an Eastern intellectual cultural elite. Throughout the film, she tries on different identities and jettisons them when they do not suit who she really is. It is not so easy to cast aside a new life in a new place when money and distance are considerable obstacles, so how do you return home? How do you learn to be alone? By reclaiming the discarded past.

The final sequence shows that Lady Bird is not a film in which Gerwig put down a tripod and effortlessly made a film. It is a shocking image of home, especially given Lady Bird’s reaction to the prospect of attending a college similar to her high school. If the saints were just people like us, then a communion of saints can exist in sacred spaces, whether consecrated by God or by man, in an appreciation of the life spread before you. Love is attention.