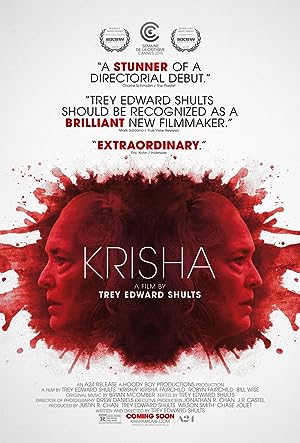

When I saw my first Trey Edward Shults film, It Comes at Night, his sophomore feature film, I despised it and almost swore off ever seeing his films again. While I did not love Waves, his third feature film, I had enough of a begrudging respect for what he was trying to accomplish and was reluctantly willing to watch his first feature film, Krisha. All of Shults’ films get rave reviews, but I did not dread the movie like his others because at least it took place on Thanksgiving, my favorite holiday and was available via streaming so all the lost time and effort to get to the movie theater would be eliminated.

Krisha is Shults’ best film. His other films are heavily melodramatic and filled with violence even if it is only briefly shown, it emotionally colors the entire movie whereas this film imbues with importance, drama and consideration more quotidian fare such as visiting family for Thanksgiving. Everything dramatic and worthy of headlines transpired ages ago away from the glare of the camera. The camera movement and proximity to the characters and editing style reflect the interior, emotional landscape of the protagonist, the titular character, a visiting family member who has not seen her family for a long time and decides that she wants to cook dinner.

While Shults clearly made a mistake trying to make an actual horror film during his second foray into films, Shults succeeds in making Krisha feel like a true horror film. I love horror movies, but if your goal is to make me feel uncomfortable and horrified, make me feel vicarious embarrassment for an on screen character. The soundtrack sets the mood and is filled with dread. He uses diegetic sounds as the calm before the storm, and when the music gets jazzy, it is like the showstopping performance that we were anticipating has finally arrived. From the extreme close ups of faces and objects to the use of slow motion and a still camera shot to focus on an unrecoverable disaster, Shults forces us to understand that these proceedings are the emotional equivalent of defusing a bomb in a crowded shopping mall or finally getting to perform in Carnegie Hall. The close up on the inside of the oven almost makes it unrecognizable or makes it seem like a stadium or a stage filled with darkness with a spotlight waiting for someone to take center stage. The background chaos, the frenetic energy and action of the characters, which is initially light and fun, then permeate Krisha’s struggle to be still, peaceful and “cool” until she gives in to that pace with utterly different results. This film is no ordinary drama.

Instead of playing it straight and giving a viewer an opportunity to brush aside the disproportionate weight that Krisha gives these moments, Shults never allows us to escape relating to her even when we no longer want to. As she gets overcome with regret over the past and her self-destructive tendencies, a television screen envelops her and acts like a thought bubble. It is scarier than Poltergeist. I love when filmmakers actually make unflinchingly, unlikeable women characters, and we still root for them. There is one scene that I consider unforgivable when I wanted to tap out because I was concerned for the other character, but just like Krisha can’t escape herself (wherever you go, there you are), we are trapped with her, but helpless to stop her, which she is also experiencing. Just when she can salvage some redeemable moment from her missteps, she acts as if she is a vengeful spirit who is compelled to disrupt and disturb others so she can exile her self-hatred and disgust or at least make it tangible so she can fight it in the material world. It is as if she is possessed, which is a great metaphor for what ails her, but unlike a person plagued with demons, her problems do not exempt her from understandable judgment and devastating disappointment.

When Krisha uses objects as substitutes for the people that she cannot get closer to, she clearly makes a discovery that I am uncertain whether to be concerned for another character’s trajectory when she finds a half-filled bottle of alcohol and drugs (are they prescribed or illegal). Because Krisha is an unreliable narrator, the ending feels as if she reimagined the earlier heartwarming moments and reconfigured them into self-condemnation, or are we still following a linear storyline? Were the earlier gentler moments truth or fiction or is the denouement?

I did not find out until after I saw Krisha that Shults and his family are actually the majority of the actors in the film, and it was filmed in his mom’s house. His aunt, Krisha Fairchild, plays the main character, and Shults plays her son. Even though they are not playing themselves, it feels real and lived in, more like a documentary than a movie, especially in the way that he includes scenes that would usually be omitted in a film: finding the right house, cooking in an unfamiliar kitchen, the awkwardness and familiar exchange of reunion among family members, settling in to your temporary accommodations. Shults uses mumblecore’s narrative and setting to give credibility to the story while using polished camera, editing and sound production to sculpt it into a sophisticated finished product and convey the wordless concepts of interior, psychological dynamic of American life-the impossible struggle to narrow the chasm between expectation and reality. This collective, family effort to bring a personal story, which is fictionalized slightly, to life on the big screen explains why the film feels so organic, textured and nuanced.

Shults is actually a solid actor in his supporting role. Directors who act in their films often allow vanity to affect how they compose the scene or temporarily centralize their character into being more pivotal than necessary. Shults strikes the perfect balance by making us always aware of his presence on the edges of every scene, but never takes the spotlight. He plays his role in a very understated way that is instantly recognizable and familiar, but conveys a wide spectrum of turbulent emotion. It makes me wonder why he does not act in his films more. I love when black actors get more work, but I wonder why Shults chooses black actors to tell his stories. I would love to say that it is because they are the best, which is true, but considering that I thought his subsequent movies are not as good, it makes me wonder why Shults is keeping his work more at arm’s length in terms of its effect on him as a person. His later work feels more theoretical and removed. I do not have a right to his stories, but his movies are better when he feels comfortable revealing himself.

Krisha is a moving, universal family story which provoked a lot of thoughts. Is it better to avoid the elephant in the room or tackle it headlong to avoid the awkward silent response to inappropriate behavior later? There is not a right answer, but I can see Shultz and Fairchild as a reconfigured, second coming of John Cassavetes and Gina Rowlands. He needs to come back home.