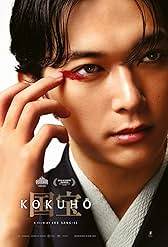

“Kokuho” (2025) means living national treasure and adapts Shuichi Yoshida’s 2018 novel, which was over eight hundred pages. From 1964 to 2014, Kikuo Tachibana (the Thai-Japanese actor, Soya Kurokawa as a child and Ryô Yoshizawa as an adult) becomes immersed in the world of kabuki acting where bloodlines matter more than hard work and merit. Will his dream of becoming the best kabuki actor ever come true? The highest grossing live action Japanese film was Japan’s submission to the 2026 Oscars “Best International Feature” category, but the Academy Award nominated it for “Makeup and Hairstyling.” With an almost three-hour runtime that feels as if it ends too soon, Americans got cheated because of the lack of a wider release and is not yet available for home viewing. It is a riveting journey of one artist’s lifetime of dedication and love.

If “Kokuho” decided not to market heavily in the US, it is probably our fault. Kabuki is older than our country. Like theater in Shakespeare’s time, women were not allowed to act, so men and boys played women characters. In kobuki, that practice persists so the actors are called onnagata. In the US, when men dress up like women professionally, it is still controversial and equated with sexuality. For most of the characters, these issues would be unfathomable, and most of the characters are depicted as heterosexual. On the other hand, unlike here, in Japan, tattoos are signs that a person could be a criminal or a member of the yakuza. The characters have multiple names: their birth name, their stage name and potentially an inherited stage name. During the film, well known pieces are performed, and director Sang-il Lee introduces the title and a summary of the plot so those who do not immediately recognize the work at first glance will not be left in the dark. Still there is not much context offered, and a lot gets lost in translation, but it did not spoil the movie for me. I loved it.

In many ways, “Kokuho” begins with the protagonist’s birth as a performer as his father, Gongoro (Masatoshi Nagase in an arresting single scene), and step mom, Matsu (Emma Miyazawa), invite a famous actor, Hanjiro Hanai (Ken Watanabe), for a New Year’s feast, which happens to include a performance featuring their son, who is so impressive that after a beautiful and tragic exterior snow fall scene, Hanjiro recruits the fifteen year old gifted boy as his apprentice, but treats him more like his adopted son hoping that the competition will push his son, Shunsuke Ogaki (Keitatsu Koshiyama as a child and Ryûsai Yokohama as an adult), to work harder instead of feeling entitled to inherit the family business. During their training, they have a chance to meet and watch Mangiku Onogawa (Min Tanaka), an actor who already achieved the titular honorific, perform. During his performance of the “Heron Maiden,” a 1762 dance-drama in which a white heron turns into a woman who suffers from unrequited love then resumes her form and vanishes, it is staged during winter with snow fall, which is Kikuo’s Rosebud.

The rest of the movie involves Kikuo’s desire to achieve artistic success and fulfillment, which was not intended to be at Shunsuke’s expense, but when it does happen, their relationship and career are in tension until someone intervenes to harmonize their path. Shunshuke knows that he is not good enough, and Kikuo internalizes others’ judgment as if he is bad then begins to fulfill their expectations, which was frustrating to watch. The cultural divide made me wonder if his haters were just privileged and entitled, or they had a point, especially given the position of the person who ultimately smooths the way. As an ignorant outsider, I never doubted Kukuo’s sincere dedication and commitment to art, not fame. I interpreted the backlash as the establishment throwing everything at him, including the kitchen sink, otherwise Shunsuke would not stand a chance. Is his sin not accepting the hierarchy even when he did not actively try to subvert it? The story arc with Harue Fukuda (Mitsuki Takahata) was downright baffling, and I need someone to explain it to me like a toddler. It does seem as if she understands that Kikuo’s only true love is his art and believes in radical acceptance. Justice for Kikuo.

Making a deal with the devil probably has different implications in Japan than here, but Kikuo is willing to give it all to be the best kabuki actor, and it shows in his community. Outside of his relationship with his master, everyone comes second to acting. He uses violent terms to describe his relatable desire for excellence, but he does not ever enjoy his success. He is riddled with fear. In a more poetic way, acting offers him an elusive feeling that he cannot get in real life, “It was scenery I’d never seen before,” i.e. that pivotal tragic moment as a child. How can he recreate the pain and beauty of that moment and convey it to others to speak to their pain and experience? How does that moment replay in his life without him trying?

A scene with a photographer is brilliant because Kikuo acts as if he lives in a different world, an enlightened, aloof existence, but the photographer is unable to surprise him, a performer with a PhD in human nature, and he stuns her with his insight. She probably took the job just to be near him and say, “Every time I saw you perform onstage, it was like a New Year celebration. It’s transformative. Drop everything and enter my world. Like you’re inviting me in. Like you’re taking me somewhere I’ve never been.” It is as if he is being pushed towards accepting a monk-like existence: alone, abused and penniless so he can better understand the tragic women characters that he plays. Is kabuki like opera in terms of its women characters so more suffering is equated with better art? It is certainly the case for Shunsuke that his best performance coincides with the lowest point in his life.

“Kokuho” is seamless. It does not feel as if anyone is acting. It is impressive that writers Satoko Okudera and Yoshida distilled a tome into a movie that has more momentum than some ninety minute movies. The production design is sumptuous. It recreates different eras, regions, stage productions and ordinary life. The stage production is no black box, sparse theater. It is ornate, detailed and traditional. Because I am an American philistine, without the dialogue, it was not obvious to me that Kikuo was a better artist than Shunsuke. It felt like a negligible margin without the onscreen context showing how they spent their time. Lee and editor Yûki Izumi create a time slip, moving forward and creating anticipation before ending one scene and transitioning to the other with rapid intercuts between the two adjacent scenes before advancing to the next scene and leaving the prior behind. Lee’s use of the bridge as a thermometer for the health of the brothers’ relationship was a good choice that did not seem too heavy handed. In one early performance, the focus on Kukuo’s foot and shifting focus on a random actor feels important, but it is only later that the reprise delivers an emotional grenade impact regarding the importance of holding that foot. It becomes an image of sacrifice and love.

If you are interested in the discourse surrounding nepo babies, “Kokuho” is a nuanced look at the other side of that issue. It requires a huge time commitment, but it will not feel like it. It could have been longer with zero complaints. Now who is going to write a paper about how it is possible that the North American drag community shares so much in common with a hundreds of years old theatrical art, particularly the dramatic on-stage costume change that results in thunderous applause, belonging to houses, adopting different names? Also a paper on how gender impacts Kikuo and forces the women to do drag while adhering to their assigned at birth gender roles?