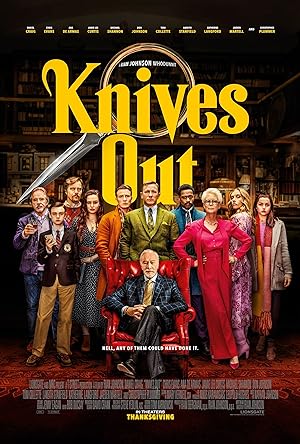

Knives Out is the kind of movie that you should watch based on the cast alone. Watch the preview, and it is the kind of movie that will leave you eager wanting to know more. Watch the actual movie, and you probably would not mind watching it again just to see if it holds together as delightfully as it did the first time around. Clearly Rian Johnson was eager to prove that he does not need a wildly successful franchise, special effects or action to get people to the theater, and I am almost ready to forgive him for Looper. Johnson delivers an entertaining murder mystery if moviegoers want to keep it superficial and a trenchant commentary on Presidon’t’s America for those with eyes to see.

Knives Out begins with the discovery of the eighty-five year old patriarch’s body, a famous mystery writer, but what happened? Two police detectives and a famous private detective are trying to uncover the secrets that everyone is trying to hide. I have rarely been into murder mysteries, and it requires a certain amount of familiarity with a genre to definitively declare Johnson’s take on the genre as subversive, but considering how much I liked it, and how much I normally lose interest in such stories, I’m going to say that it is different in the best way possible.

Knives Out makes a memorable first impression with the simple act of discovering the body. Johnson nails the humor by injecting the practicalities of quotidian life into the genre in much the same way that Scream used meta commentary about movies to breathe fresh life into the horror franchise. Then it feels as if the movie’s narrative style is going to head in one direction with intertitles orienting the viewer to the time and what we believe are the main characters, the third generation of the patriarch’s family (four generations under one roof—it is amazing that no one died earlier). Johnson soon abandons this approach, which would normally bug me, but it did not. It was clear that once it served its purpose, to orient us regarding each segment of the family. The explicit question is who murdered the patriarch, but the real question is who will assume his mantle of leadership.

Normally the protagonist in the murder mystery genre is the quirky detective, which in this case, would be Daniel Craig’s Benoit Blanc sporting a Southern accent that sticks out in the stronghold of Yankee (new) wealth clothed in the myth of self-sufficiency, success, hard work and tolerance, but Knives Out points our sympathies in an unexpected direction, which I won’t spoil for you, but I have noticed that other reviewers do. During the interrogation, Johnson cleverly shows us the characters’ subjective memories, but not from their point of view. Everyone is the star of his or her own movie and in memories of their last night together, they take prominent places in proximity to their dad while omitting any detail that threatens to mar the image of a happy family to outsiders. The only question is whether or not they are not only lying to others, but to themselves. One character never lies to herself in a self-serving way. It is interesting that the distance between the camera and its subject actually indicates the accuracy of the veracity of the memory and the closeness of the relationship.

Johnson flips the genre on its head by using this window into his characters’ minds to make us root against the authorities and the truth coming out. On the other hand, while Knives Out makes fun of the blowhard famous detective, it ultimately has faith in the system to administer justice and holds it up as an institution that can be trusted without bias even if the system or especially because a Southern man is at the helm. In this way, Johnson’s film is still old-fashioned and adheres to the genre in a way that reality does not.

It is interesting that Knives Out came out during the same year as Queen & Slim. Both movies are invested in reversing migration from the North to the South as a route to freedom either literally or psychologically. The North likes to believe that because that region did not have legalized slavery, its inhabitants are exempt from the sin of racism. Queen & Slim starts from a place of institutionalized, implicit bias in a Northern state whereas Johnson’s film depicts coded, social bias when explicit bias would not be acceptable versus explicit bias when it would be acceptable such as ridicule over the detective’s accent. There is an intellectual snobbery of Yankees over Southerners warranted or not depending on the individual (The New Yorker article versus a tweet about The New Yorker article).

Knives Out provides commentary on class in the same way that Parasite does and in a more consistent way than Beatriz at Dinner in the way that it explores the language used between employers and employees. There is a discomfort over the power imbalance so certain words are used to imply that the employee’s humanity is still recognized. By simply flipping who is using the same words, Johnson reveals the true meaning. There is a lie of benevolence and good intention implicit in words of comfort and caring. Murder is simply the end result of a polite, quiet struggle to retain power.

Knives Out is far from a perfect film in the questions that it leaves unasked and unanswered, which may be explained by the assumptions that Johnson brings to his movie. If this brood is so dreadful, then the patriarch caused it and waited too long to rectify it, but what about his wife, their mother? The offscreen death of two characters, one of his sons and the never mentioned matriarch, leaves a question of what happened to them. The first and second generation get off too easy in a film devoted to putting people in their proper place. If the first generation is not complicit, then what happens in the film to that generation is egregious and is treated too lightly, but if the first generation is complicit, then it should have briefly been explored. Reach a certain age, and people are entirely too willing to assume that you are wise or harmlessly ineffectual, which seems to be the underlying characteristics of the first and second generation. While good parents can produce horrible children, it feels as if Johnson’s critical eye is missing something that Shakespeare’s King Lear does not because Johnson likes the patriarch and ultimately believes that he deserved to be the center of attention and have a better family. While I think that Johnson is somewhat right considering that we see the patriarch put his money where his mouth was, he literally had skin in the game, it feels like we missed a come to Jesus moment, a change in character, which is understandable since we only see him for one day out of his entire life.

Knives Out proves that Johnson has staked his claim as an American filmmaking contender who can generate excitement simply with the use of a good story, acting and directing. His use of humor in a murder mystery and ability to infuse deeper meaning without weighing down the momentum of the narrative’s trajectory shows that his instincts are sound and his work is superb.