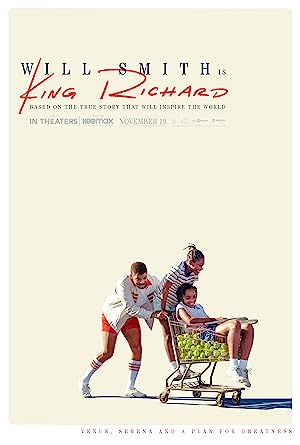

“King Richard” (2021) marks Reinaldo Marcus Green’s third feature as a director and second biopic after “Joe Bell” (2021). The title refers to Richard Williams, Venus and Serena Williams’ father, and depicts how the plan for them to emerge from Compton as world class professional tennis players unfolded.

I am a sports atheist, but I am into black excellence so even I am rooting for the Williams’ sisters and understand that Serena is a real-life Wonder Woman competing while pregnant and in peril. I have also been following Green’s career, and while I do not love his work, I am excited to see how he is advancing though a unique, recognizable style has not emerged. It appeared that his trademark were nonlinear narratives or fractured narratives seen through multiple characters’ eyes, but this movie is chronological and straightforward, easy to consume. Directing a biopic starring Will Smith is an achievement.

“King Richard” felt like a chance for Smith to act, which he does well, in the vein of characters such as Chris Gardner in “The Pursuit of Happyness” (2006) and “Concussion” (2015) though it feels more like a continuation of the first since Richard is a man trying to leap over class and racial lines to get a better life for his family. He succeeded in showing the conflict between ambition and protection and embodied the sincere hustle vibe necessary for a big family to survive. Leaning into a lisp, Smith abandons his trademark action star exuberance and energy to create a plausible portrait of a security guard whom local ruffians beat up.

My criticism and praise of “King Richard” stem from the same dynamic. The Williams family succeeded so the plan, regardless of its flaws, objectively worked, but the film depicts it as if it is the only feasible option in Compton or the broader tennis world. Other alternatives are unhealthy. If the Williams’ way is the only option, it is inspirational, but unachievable for most people.

In Compton, the alternatives are presented as gang member or sex worker, but there are references of the Williams family worshipping in congregational settings so there were opportunities to casually show other black people living a decent, normal life under hostile conditions. “King Richard” uses familiar imagery such as drive-bys and gangs hanging out, media imagery used to teach us to equate black neighborhoods with criminal behavior thus increasing the viewer’s investment in Richard’s plan to escape this environment.

In contrast, “King Richard” does something not often shown in media, but focuses on the psychological abuse of young, affluent teenage girls and how it leads to a negative self-image. DCF is less likely to be called or intervene depending on the race and socioeconomic background of the family. The film has a montage of white girls crumbling—a point of triumph for the Williams sisters, but a cautionary tale for Richard. He recognizes that he has put his daughters in an unhealthy environment that could just as easily lead to drug abuse. These images are less prevalent in the media though the image of the cold, emotionally distant affluent family is played for laughs and drama. This film takes it seriously. It also shows occasional moments of connection between the Williams sisters and the competitors. It would have been nice to see if those families were normal, especially when we get to Rick Macci’s camp.

Side note: there is a scene involving DCF. Because the viewer is watching a movie, Richard’s speech about this phenomenon of overlooking affluent abuse is rousing for us, but if you were an actual DCF worker visiting the home and knew nothing about the family, you would be shaking your head in wonder over the non sequitur and just be waiting for a pause to get out of there or a word in.

“King Richard” prioritizes the family unity narrative over accurate representation of the full spectrum of people that the Williams family encountered on their way up. If leaning into negative media tropes of black people being violent serve to advance that priority, Green uses it. If being countercultural and replicating for the viewer the shock that many financially disadvantaged people of color experience when they enter affluent white spaces and witness severe neglect, Green will use it. If Green has a style, it is an ability to give his customer what they want and being as mainstream as possible while injecting now acceptable, formerly controversial topics into the narrative without alienating audiences. For the world to be truly post racial, we do not need black excellence though we love it, we need black serviceable, reliable, middle of the road, a steady paycheck. When we get a black Uwe Boll, then we know that we have made progress.

Please note that “King Richard” omits the fact that he deliberately chose to live in Compton though he could live in a better neighborhood. While the movie touches on gang members beginning to protect the Williams family, on occasion, they tried to intervene to protect the children from what they deemed as verbal abuse so DCF and gangs have something in common.

Kudos goes to Jon Bernthal, who plays Macci, acting against type as a pushover American tennis coach who lets Richard use his facilities and resources without the Williams family holding up their end of the bargain. I am used to Bernthal playing physically violent roles of affable, but broken men. As Rick, Bernthal is self-effacing and so good natured that I want him to win an Oscar for Supporting Actor. He has real range and is one of the greatest, living American actors whom we take for granted.

Before seeing “King Richard,” I heard complaints that the Williams sisters did not get enough screentime, but considering that they are executive producers, I disregarded it. I also heard that it whitewashed Richard as a family man, but maybe these critics missed Aunanue Ellis’ outstanding speech. Ellis plays Brandy, the Williams matriarch. Because of their religion, in public, she backs up her husband, but privately she reads him for filth for failing as a father and a significant other in his prior relationships. The film makes two important points. Richard’s plan is their plan. He could not plan without her. Alone, he is a failure and quitter.

“King Richard” also suggests that Serena (Demi Singleton, who bears an uncanny resemblance), who gets less screentime than Venus (Saniyya Sidney), surpassed her sister’s accomplishments because their mother coached Serena more than Venus and not getting Richard’s full attention gave her more freedom to develop her identity, which is Richard’s priority, but because of his personality, he tends to suck all the oxygen out of the room. The film depicts Venus having to fight her dad’s instinct to dominate, which paves the path for her younger sister. People complained about the disproportionate focus, but this movie only chronicles their early career and is not focused on them so it makes sense that the film would devote more time to Venus. Kudos to Singleton and Sidney for learning how to play tennis after getting the role. I could not play tennis at all, and the added pressure of the spotlight could be an incentive or a choking catalyst.

While “King Richard” could have benefitted from a shorter run time, it is an entertaining, inspiring, and crowd-pleasing film. Even a viewer unfamiliar with tennis will be able to follow the story.

I have one question. When Venus is playing Arantxa Sanchez Vicario, Sanchez Vicario always has a tennis ball in the middle of her back. Why?