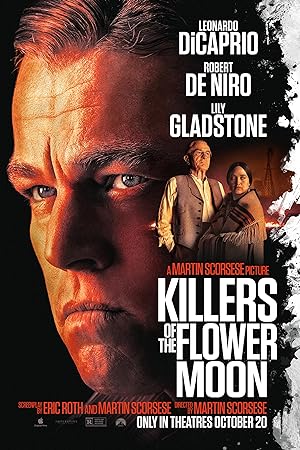

“Killers of the Flower Moon” (2023) is a film adaptation of David Grann’s nonfiction book, “Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI.” Martin Scorsese directed and cowrote the screenplay with Grann and Eric Roth, a scrappy young writer who wrote little known films like “Forrest Gump” (1994), “Ali” (2001), “Munich” (2005) and “A Star Is Born” (2018). Big hitters! Fresh from the war, WWI vet Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) visits his Uncle Bill (Robert De Niro, resembling Truman) and brother Byron (Scott Shepherd) in the hopes of finding success and love. He finds both in Mollie (Lily Gladstone), a full-blooded member of the Osage tribe with headrights to the oil profits. When Osage tribe members start dying under mysterious circumstances, Mollie becomes determined to stop the murderer unaware that they may be the people whom she considers family and friends.

Full disclosure: I have not read the book and plan to so my entire view of the movie may change if it is a faithful adaptation. Intellectually I understand why “Killers of the Flower Moon” is a good movie. It sheds light on a true story and paints a sinister image of how exploitation and racism can even permeate a community of wealthy Native Americans and unflinchingly reveals how their two-faced white neighbors can profess to be their friends while not thinking of them as human beings, but living, breathing, walking ATMs that they can murder to become wealthy. It appears that the Osage people and descendants of the murder victims are proud of this movie because a Scorsese film with famous stars is guaranteed to tell their story to a huge audience and offer them a chance to start their movie careers in front of and behind the camera. Their dying language is spoken on screen and will hopefully get a second life. Their rich culture provides a powerful backdrop and contrasts the crass, rowdy mainstream culture that supplanted the indigenous one, which was detrimental to both. It must be vindicating to see the admission of a conspiracy on the big screen.

I hated it. “Killers of the Flower Moon” is just another Scorsese gangster film in social conscious drag. On those terms, it is a sublime, unrelenting film that mines the humor from a grim situation and nails the period in a way that no other film has. I went into the movie not knowing anything about the film but was disappointed. I don’t need yet another movie primarily from the point of view of a white guy getting to know the Osage people or humanizing bad people. Scorsese is at a point in his career where he could make a movie about my cat, and everyone would watch it. Scorsese made a choice to center yet another white character and make the Osage people supporting characters in their own story. Many have pointed out that it is a movie for white people to become aware of their privilege and not find a way to avoid historical accountability. I agree. Under those terms, Scorsese’s film is a triumph, but it is another missed opportunity to rectify that privilege and center an indigenous person. The presumption of white people’s innate attribution of goodness then the constant need to shock audiences that gasp, white people are fallible human beings created of great evil is another form of privilege that apparently most audiences must watch then forget while the rest of us are doomed to repeat the same storyline. Revealing that white people can be criminals for 3.5 hours is redundant and uninteresting for anyone with the slightest understanding of world history or possess critical thinking skills and eyes, leave their house, and look around them.

Unfortunately in many parts of the US, people are trying to outlaw history so I get that I am coming from a privileged, educated position. (Or alternatively I do not have the luxury to ignore reality/history because my life depends on it. De Niro promoted the film and expressed shock learning about the contemporaneous destruction of Black Wall Street. Sir, you have Black children, and at the big age of eighty, you just found out about it.) Scorsese accomplishes the same goal by sprinkling a supporting character, Molly’s guardian (Gene Jones), in unexpected contexts: a KKK member, a juror, a member of the criminal inner circle. The film depicts a vast gorgeous tableau that indicts almost every white community member for playing a role, especially the ones that never get publicly exposed.

After watching the “Killers of the Flower Moon,” I found out that Scorsese chose Ernest as the protagonist because the book had the least information about him so they had more wiggle room to take liberties with his story. Compared to the majority of Hollywood cinema which demonized Native Americans, Scorsese is balancing the scales and struck a staggering blow, but it is what should have been done long ago and is the bare minimum. Scorsese is getting a lot of flack for taking this stance from the other end of the aisle. He’ll be fine and does not need more accolades to mend his wounds.

“Killers of the Flower Moon” should have an Osage protagonist, preferably Mollie, the woman at the center of solving the conspiracy and almost becoming a victim of it. If Gladstone deserves an Oscar, it is for convincingly depicting a regal, wise, determined woman who can simultaneously be oblivious to the evil openly lurking in her home. A lesser actor would leave their character vulnerable to victim blaming for not having the benefit of being an audience member or possessing hindsight. In many ways, this movie is guilty of doing the same thing to Molly that the homicidal conspirators did—profess to love her, silence her by relegating her to the side and capitalizing from the association by harming and supplanting her. People are praising DiCaprio for urging Scorsese to expand Mollie’s role, but real sacrifice would be insisting on becoming a supporting character. (See Brad Pitt’s career as a producer.)

Molly’s romantic history is referenced late in the film, and it is primarily as a vehicle showing Ernest’s slight jealousy and resentment that his wife did not share a detail of her past before him, but the denouement suggests a more intriguing concept. Molly erases men from her history that do not deserve her. It is such an underutilized idea of women creating history and them omitting bad characters, which is a huge contrast to cinematic choices. It also seemed counterintuitive that Molly detested noise but was fine with Ernest and his family invading her house.

Perhaps Molly is too respectable to be an appropriate Scorsese protagonist. Another alternative could have been Anna (Cara Jade Myers), a hard drinking, gun slinging, fractious woman, and Molly’s sister. While she is a woman who adopted colonizer ways, looking like a flapper woman, her mother, Lizzie (Tantoo Cardinal), clearly preferred her rebellious daughter over Molly. Without many lines, Lizzie’s story arc is the most poetic and complete in the way that she withdraws herself from socializing as a way of signaling her disapproval, and her character introducing an owl, supernatural theme, was an underutilized, lyrical device.

If having a flawed, indigenous woman protagonist would take too much effort and too risky, another tragic alternative was Henry Roan (William Belleau), an alcohol self-medicating indigenous man who suffered from mental health issues and a crisis of masculinity. Who needs more humanizing and understanding than the stereotype of the alcoholic Native American man? Movies are empathy machines that help people relate to people that they may otherwise never encounter. While watching the “Killers of the Flower Moon” and watching the Native American characters, ask yourself what you will remember about every Native American character when you leave. They appear in clusters at the film’s bookends and throughout the film, but do you know their names, their position in the community, their hopes, their dreams, their habits, etc.?

“Killers of the Flower Moon” has amazing talent, and it is unfair to critique a film for not meeting expectations as opposed to the actual film, but it is such a lost opportunity to make a revolutionary film. It may take some time for me to watch it again so I can judge it on its own merits.