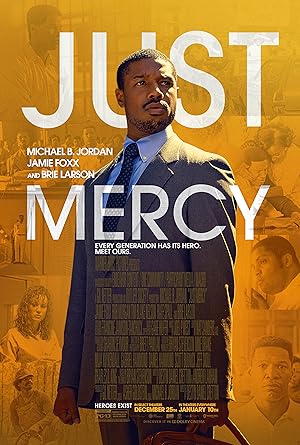

Just Mercy is a film adaptation of Bryan Stevenson’s memoir, which primarily focuses on how Stevenson, played by Michael B. Jordan, decided to start the Equal Justice Initiative in Alabama and chronicles a couple of his early cases from 1987 through 1993 in Monroe County, Alabama. Destin Daniel Cretton directed it, and he is one of my favorite directors regarding his empathetic heart in such films as Short Term 12 and The Glass Castle which tastefully, sensitively and realistically addresses issues of child abuse, including sexual, without being exploitive or clinical. Cretton’s films are generally biographical, and his primary goal seems to be distill lives into limited amount of time and space so his viewers leave caring about people and have a sense that those lives are continuing off screen. Imagine a more conventional, family friendly Marielle Heller.

I saw Just Mercy with a group of friends from church, which was the main incentive for seeing it. At least if we had to pay to see black pain instead of getting it for free, we could do it together and find a way to have our own good time in the midst of all our sorrow. I probably would have seen it anyway because I enjoy Cretton’s work and enjoy supporting a director of color with a predominantly black cast and Cretton’s favorite actor, Brie Larson, who for the first time was not starring in his film and was playing the one real white ally in the movie, Eva Ansley.

Just Mercy is not the kind of movie that will be remembered for being visually outstanding. Cretton is no Barry Jenkins’ If Beale Street Could Talk. I do not think that anyone will be analyzing still shots of his film to imitate them in the future. This film may be his most germane film for our times, but it is not one of his most consistently powerful ones because he seemed handcuffed to a linear narrative, which I generally prefer, but is not his customary style of using flashbacks or telling the story in thematic order, to remain faithful to the story. He veers dangerously close to television movie territory in his efforts to recreate well known points in the story by using intertitles to indicate the date and location, but then was inconsistent in his format wither by giving a specific date or indicating how much time had passed, which in a story with more moving pieces, could have gotten confusing for viewers, but did not. It is his second period piece (so much bad hair, but shout out to the production designer for finding that halogen light, which is accurate).

Just Mercy manages to just escape the Scylla and Charybdis of the civil rights movie tropes by not bowing to the great man biography genre although it traffics in many others. Instead Cretton emphasizes the regularness and vulnerability of most of his characters. He erases the chasm between the ones fighting for justice and the ones who are in the dock. It is the opposite of the (white) savior trope. It is a but for the grace of God go I, a sameness and equality of all people, humanity, for those who see it in others. Cretton’s goal is not to be considered a great director. His goal is to get his viewer to love a murderer, a liar, a coward as much as the story’s hero and the innocent, wrongfully accused man…not a racist sheriff. Without repentance or the potential for repentance, Cretton will keep you two dimensional and consign that character to trope hell. Otherwise he is trying to win hearts and minds and uses his film in the way that Stevenson probably wanted him to—as a call to action to humanize and look for the lost sheep, fight for the poor and the truth, offer bureaucracies and institutions an opportunity to repent like an old, crazy Biblical prophet. He succeeded in his goal.

Just Mercy is distinguished by its use of sound as a way to continue to be connected to your community and show compassion and counterintuitive use of light in various settings. Usually prison settings are shot to be gloomy and oppressive, but the actual cells and uniforms are gleaming white as if to suggest that death row is adjacent to heaven, and these are the saints wrongfully accused and persecuted for Jesus’ sake. The closer that characters get to the outside world is when it gets darker, and if you pay close attention to the wardrobe choice, it is only at the point of vindication that Foxx’s character gets a black blazer. Freedom means being vulnerable, living in a fallen world, being prey to the snares of wicked men at night. Cretton, in a less artistically striking way from A Hidden Place, seems to equate proximity to nature as being closer to God and the world in the way that He initially intended it, but unlike that film, the light exists because the prisoners are the church so they transmit His light. If you think that I am reading into something that Cretton was not trying to do, make no mistake. Cretton was a home-schooled Christian kid, but not the scary kind apparently—he was the kind that got taught all men are created in God’s image.

If I had to critique Just Mercy, it is that Cretton depicts all women regardless of race as more compassionate than the white men in this film, which may actually be true in this specific story, but statistics show that during November 2017, sixty three percent of white women voted for Roy Moore to be Alabama’s senator even after revelations that Moore was allegedly a pedophile of their children. That percentage is higher than the national average of fifty-two percent of white women who voted for Presidon’t in November 2016. So while I hope that Cretton’s depiction was accurate and those women were giving their husbands and colleagues the side eye for perpetuating lies in the justice system, statistically they probably were cheering them on for doing a good job. To be fair, the movies credits show that people kept reelecting the racist sheriff long after his wrongdoing was revealed repeatedly in court, but everyone can’t be Larson, and in Alabama, it is not the forty-eight percent, but the thirty-seven percent.

Just Mercy succeeds at evoking empathy in its audience for those who are normally judged harshly. It engenders a goal towards community and equality in the justice system as opposed to increasing division and the chasm between status. Now I want to read the memoir and see the HBO documentary about Stevenson’s life, True Justice: Bryan Stevenson’s Fight for Equality. For those who bemoan the film’s lack of innovation, you are right, but unfortunately the real life stories of bias and injustice seem timeless in their banality of evil, and I fear that any innovation would spur evil to find new ways to destroy lives. We must not let our hearts get hard to stories of injustice simply because they seem familiar. Some films are great works of art and a call to action, but if you can only succeed at doing one, maybe the latter should be the priority.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.