Junebug is proof that Americans, like the French, have the capacity to make incredibly simple, beautiful films about life, love and death without becoming melodramatic, defaulting to tropes or archetypes or being so artsy fartsy that the film becomes obtuse and offensive to the average viewer. This movie felt organic and filled with real people instead of quirky inventions for the page forced to come to life by a misguided filmmaker. I came to this film with no expectations, and I am not entirely sure how it ended up in my queue. The probable reason is that Amy Adams is an underrated actor, and I probably added all her movies to my queue at some point.

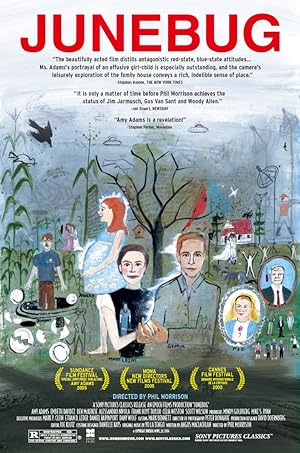

I did not understand the significance of the opening shot and sequence in Junebug, but then we see trees with the title in red bold all caps title superimposed over the trees, which will make sense by the end of the film. Then the film briefly starts in Chicago so we can witness how the newlyweds meet. If the viewer is unfamiliar with North Carolina, the viewer is supposed to empathize with Madeline, the newlywed wife and art dealer, played perfectly by Schindler’s List’s Embeth Davidtz, who gets her husband, George, played by the criminally underrated, multilingual American chameleon Alessandro Nivola, to accompany with her to North Carolina for her to court an artist and to meet his family for the first time. Even though we never find out what George does for a living, it is implied that it comes with enough good fortune to travel comfortably in Madeline’s circle and be the butt of some teasing from his family about doing nothing. The movie deftly omits details without making me think that the filmmakers never considered those details. The filmmakers just chose not to do a prose dump and keep it realistic. His brother, Johnny, played by Gotham’s Ben McKenzie, who finally made me appreciate that he is actually a brilliant actor who is not challenged enough, and Johnny’s pregnant wife, Ashley, played by Adams, still lives at home with his parents, Eugene, played by The Walking Dead’s Scott Wilson (Herschel), and Peg, played by the magnificent character actor Celia Watson. The movie depicts Madeline’s first weekend as a member of this family.

Junebug may be a perfect movie. I no longer have favorite movies, but when I was younger, there was a rotation of films that I could rewatch and have the same strong feeling with each viewing, and I suspect that Junebug could easily slip into that rotation. It is a film that knows that it is a film. You have to give it your complete attention because it somehow is able to simultaneously depict the film as unfolding in our present time, but also evoke the feeling that we are witnessing a memory with a love and bittersweet helplessness to intervene in the present moment to help the characters connect directed at even the most ornery characters by allowing the camera to linger in empty rooms and just hear the disembodied voices of the characters. The film shows the characters as they appear to others in different contexts and their inner lives. Each character feels deeply, is trying to bring their full, sincere and true selves to each situation, which is impossible because each character carries the scars of the never fully divulged past, which holds them back in the present because they are protecting themselves. The counterintuitive focus of the camera captures the innate awkwardness of even the most honest interaction. There is a scene when four people hurriedly rush into a car, and one person stays behind. That person waves along with a neighbor. Instead of following the excitement, the car, the filmmaker chooses to show how the person and neighbor act after the car leaves. What do you do? Sure, they could talk then go their separate ways or just immediately live their individual lives, and we witness that indecision, “What should I do?” There are no right answer, but each possible interaction or lack thereof has a consequence for the individual, the group and the community.

Junebug captures how hard it is for human beings to connect and how beautiful it is when they succeed, especially contrasted with nature. After the awkward neighbor reaction, we see insects have no problem buzzing around each other with ease over the lawn that they could have communed. The trees from the opening credits collectively bear witness to later failures and sorrows. Even though they are complete opposites in terms of life experience and demeanor, Madeline and Ashley are very similar—eager to create a family, cannot help being themselves even when rejected. By the end of the film, I began to wonder if Madeline was more emotionally vulnerable than Ashley. At the beginning of the film, the brothers also seem like opposites, but by the end of the film, the viewer witnesses the similar ways in which they do not verbalize their expectations and disappointments then emotionally withdraw and punish others when hurt. For me, the real revelation in this film was McKenzie because he seems like he usually plays the same role, and it felt as if any casting director could exchange him for a better actor which would make the overall product better, but apparently he had the capacity to give Aldis Hodge’s Clemency’s levels of emotional turmoil and range and had to put his light under a bushel to pay the bills. People, stop making McKenzie play basic white guy when he is a thespian. The hell!?! There is a scene between Nivola (he acts in multiple languages, you don’t know about Nivola) and McKenzie when McKenzie plays the scene in three different ways. McKenzie’s voice sounds calm and resigned, his body is brash and viperous, and his face is turbulent with conflicting emotions: shock, horror, concern, fear, regret. Who is this actor and where has he been? The film gives us a glimpse of Johnny in a different context. He is a completely different person. He may be the most fascinating person in the film, and I found myself relating to him on a deeper level than just demographics.

Junebug depicts the culture clash without mocking the individual clashing cultures. Even though I am a born and bred New Yorker who fears the South as if the US will explicitly revoke the thirteenth amendment any second, I have become increasingly agitated at the lazy filmmaking math of equating Southern with evil and not understanding that not all the Southern accents sound the same. They vary based on state. I am not saying that I am Henry Higgins and can detect the differences, but I know enough to be sick of the unearned generalizations. On the flipside, I appreciated that Madeline was not depicted as a snob, cold, superior or evil for being from elsewhere.

I wholeheartedly recommend watching Junebug. I wish that I could watch it repeatedly. I was so engrossed in the film and its characters that I began thinking of them as real people.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

I am mad at George. He basically abandons Madeline for the entire weekend, which is understandable because it is clear that he has unarticulated, weighty issues with coming home and is avoiding his family as much as possible while staying the weekend. Only Ashley provides the social lubrication to help Madeline try to fit in with the family with limited success. Peg already hates Madeline for the honest name mistake, but also because she would hate anyone for taking away her favorite son. Madeline is completely invested in Ashley, wants to go to the hospital then Peg pushes her away. Eugene and Ashley are too busy focusing on Ashley to notice Madeline’s exile and rescue her, which is completely normal because they should be more focused on more urgent concerns. Madeline accepts the situation and moves on. George is not there to witness her brief exile from the family then blames her for it. To be fair, I can understand being appalled that Madeline chooses business over the family without that information, but dude, she spent more time with the family than you so I thought he was not giving her credit based on everything she did up to that point to integrate herself into the family. He was really angry at himself and taking it out on her. For me, the unforgiveable point is when he won’t let her visit Ashley at the hospital because he just wants to flee the uncomfortable feelings that the family evokes in him about himseld, but he makes it seem like a punishment for her slip. I just felt as if Madeline was not emotionally safe in this marriage because he was not being honest with her, and he felt free to use her as a scapegoat. Up to that point, their relationship is completely reciprocal, but I could see the seeds of destruction, especially if he leads her to believe, and she agrees that she is at fault and must make up to him. Unlike Ashley, she just crumples at the withdrawal, and it was heartbreaking to see that she won’t be able to handle getting kicked in the gut by three out of five members of her family.

Though I liked Madeline as a person, because I can see her in all contexts, I was also horrified by her actions. One minute, she is fundraising for Jesse Jackson Jr., whom I have no knowledge of his substantive positions on any issue, then she is soliciting a totally racist artist and briefly considers using that racism to her advantage to get him to sign the contract. It was such a liberal, intelligentsia, forty-seven percent thing to do that I was not even mad at her. It was not even a shock. When I saw the black scout waiting outside the artist’s home, I knew what was up. She totally does not understand that she is vindicating these beliefs that she does not hold by refusing to challenge them and just being silent in her disagreement. She does not see such things as deal breakers, but what she could work around, and I would not feel safe going with her anywhere, which is why it makes complete sense on a lighter, emotional level, why she cannot keep herself safe. This openness to the world and concepts can also lead you into some wounding situations.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.