Pedro Almodovar is one of the greatest living film directors, the rightful heir to Hitchcock’s throne with his mix of psychosexual driven dramas and an innovative storyteller who delivers uniquely crafted narratives. When Hulu notified me that his films were going to expire and be removed on June 20, 2017, I decided to watch all his films, including the ones that I already saw. This review is the thirteenth in a summer series that reflect on his films and contains spoilers.

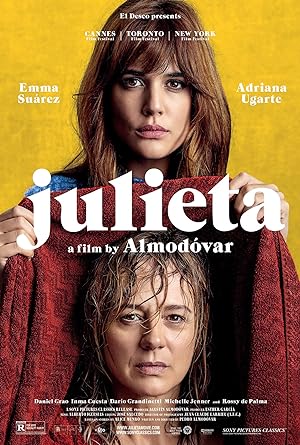

Julieta is Almodovar’s most recent film. Unlike most of his films other than All About My Mother and Talk to Her, I was aware when Julieta was in theaters, but chose not to see it because it sounded too sad, and after November 2016, a sad movie is the last thing that I wanted to see even if Almodovar directed it. Even though I regret not seeing it on the big screen, I do not think that it would have been the right time. I think the release date affected reviewers too because the feedback for the film was tepid. My timing was perfect. I saw it soon after Volver after waiting for a considerable time to get a DVD copy from my library. Julieta felt like an unofficial reprise of Volver. I decided to watch it again by streaming, but it is only available to purchase on Amazon Video and YouTube. So I ended up spending more money on Julieta than if I had seen it in theaters, and considering how much I owe Almodovar, it is a drop in the ocean.

Julieta is about the stories that we tell ourselves when we experience loss, specifically how women centralize themselves as the precipitating cause of a calamity and find a way to make sense of that loss. In the movie, loss can be death, but includes the voluntary absence of a loved one, which feels personal. Ultimately Almodovar dismisses our rationalizations: you don’t know why, it is not about you even if you are involved in the story, it does not matter, just live fully with no secrets.

Julieta begins near the end with the titular character getting ready to move with her current love interest until a chance encounter with a person from the past plunges her back into a traumatic experience in which she experienced no closure. She returns to the scene of the crime, the place where she last suppressed her trauma. Then the film’s events parallel the present with depictions of her written recollections of the past, a letter to her daughter that she cannot send, beginning with how she met her daughter’s father, which is also the point when she conceived her daughter. Both stories move forward until the past story arrives at the point when she met her current love interest then the film only unfolds through the present day.

We do not realize until the middle of the film that Julieta is really a film about the titular character’s relationship with her daughter, whom she has not seen in twelve years. Even though she was moving, she was not really ready to move on so instead she recreates the past and reestablishes what few ties she has to her daughter by staying in their old apartment and immerses herself in despair. When she discovers that she may not have even been a factor in her loss, she tries to commit suicide. When she is finally ready to move on, she finally gets a letter with a return address from her daughter, who has just lost a child and realizes what pain she inadvertently inflicted on her mother.

During the depictions of the past, Julieta is portrayed as a haunted, guilty woman. From Julieta’s perspective, she sees a pair of women who look like they are judging her as she walks through a train car before anything has even happened. She blames herself for a man committing suicide. We find out later that her train ride may have disturbed her because she chose to leave home and not care for her mother. She blames herself for her husband’s death. She blames herself for her daughter’s estrangement. When she is not blaming herself, but seizing happiness, there are people who happily pick up the slack. She thinks that her husband’s housekeeper judges her as the other woman for appearing so soon after her husband’s first wife’s death and then for her husband’s infidelity when Julieta considers returning to teaching the classic literature like The Odyssey.

Julieta was raised outside of the church and initially chooses adventure, pontos, the high sea, but she is still slave to something more ancient than the Christian concept of original sin, Greek tragedy. She chooses the gods. She falls in love with a man of the sea, a fisherman, but he is not a fisher of men, but a fisher of women. She chooses Odysseus, not Jesus, but she does not imagine herself to be Penelope. Her students liken her to Calypso because of her beauty, but they are unaware of her small town/countryside origins, which is similar to Calypso’s association with the land. When she is happy, she waits for the other shoe to drop, and because she is alive, it does. She eventually flees the sea, but never returns to the land. She establishes a pattern. Julieta runs away from memories of pain instead of tackling them. She stops choosing adventure and becomes her mother, a woman unable to interact with the world and is cared for by others.

It would be a mistake for viewers to completely believe Julieta’s perception of events. Those women on the train may have seen her, but they appear completely normal when they interact with her and the train conductor. Xoan, her husband, correctly explains that the man planned to commit suicide before meeting her otherwise his luggage would not be empty. The housekeeper greets her happily when she returns from visiting her parents. Their first and last interaction could be reinterpreted as an effort to warn her from future heartbreak over Xoan’s long-term sexual affair with Ava. Julieta is projecting her guilt and self-condemnation on to others. She judges her father for doing what she did: relegating her mother to the sidelines so she can have a full life. She and her father both have affairs before the first relationship is legally over. She sleeps with Xoan while his wife is alive, but a vegetable. Her father sleeps with his wife’s caretaker while his wife has dementia. She never returns to visit her father because she feels betrayed, but she is also exorcising her guilt by externalizing it. She is simultaneously the other woman and her mother’s replacement by prioritizing her role as mother and wife.

When her daughter leaves her, Julieta assumes that it is similar to her reasons for leaving her parents and plunges into further self-condemnation. Julieta’s pattern is an original sin suffered by women in particular—the nagging doubt that you are too sexual, not a good enough daughter, wife, mother. She internalizes guilt for random events that only tangentially relates to her. She has a right to be angry that her husband had an affair. She did not kill him, and he is an experienced fisherman who should have known not to go out to sea when the weather was bad. Even though Julieta’s mother never directed any recriminations at Julieta, Julieta imagines a disapproving mother in the form of the family housekeeper accusing her for prioritizing her career over family instead of realizing that it is class warfare and a possible rivalry over Xoan’s affections. Her daughter possibly left because of heartbreak and self-condemnation, not because she was too emotionally traumatized by her husband’s death to be a good mother. The only relationship free from problems is her friendship with Ava, her husband’s mistress

Julieta spends so much time centralizing her role in her daughter’s story that when the possible real reason is revealed, it is tragic for an entirely different reason. Just like Julieta’s mother makes very few appearances in the film, if her daughter had a movie devoted to her past, Julieta would not even rate as a supporting actor in that film yet she has expended so much emotional energy over that loss. It is also tragic because while parents are rejecting their children for being gay, Antia rejects her past, including Julileta, for not caring about her sexuality at all. I actually saw this plot twist coming because of how close the girls were, the way that Antia dressed and their love of basketball.

Whereas Julieta chooses mythology, the ocean and a man of the ocean like Odysseus, Antia chooses original sin, the rock, the mountains and a fisherman like Jesus, to explain her self-condemnation and loss. They both suffer from the same disease and waste a lot of time and love in order to heal the trauma of loss by creating tragic internal stories that elevate their role in the loss. There is no drug or alcohol use in Julieta, but the titular character’s addiction is not her daughter, which is what she says, but the rationalization of loss as not random or not caused by herself. In an early shot, the sterile background of her kitchen frames Julieta while her current love interest is framed by a clock and a red wall. Julieta is addicted to living in the past, not truly learning to live with pain and not moving forward.

Julieta and Antia falsely believe that eternal life, a life without death, is what should be desired on earth as promised by Calypso so when they are confronted with death, they feel responsible as if there was another alternative, which Odysseus rejects. While I would not recommend watching the following movies, I do think there is a relationship between Lars von Trier’s Antichrist, Melancholia and Nymphomaniac to Julieta, but Almodovar’s treatment of loss, grief and nature is much healthier than von Trier’s belief that nature is evil, and we are doomed. While the appearance of the stag is followed by death, and the role of branches alarms the main character in Julieta and Antichrist, in Julieta, it is a coincidence or a sign of being responsive to life. Almodovar exorcises the tragic instincts that plague von Trier’s films. Life is beautiful, and death is a part of life. Ava tells Julieta that the people from Xoan’s region are not easily knocked down by the wind. Julieta is easily knocked down and like von Trier’s characters, has not found joy amidst the pain of nature. The train, a central location to many Hitchcock films, is not only a way to throw strangers together and stir up sexual attraction, but like in All About My Mother, acts as an important transition point to the story.

Casting Dario Grandinetti as Lorenzo, Julieta’s current love interest and second fiddle, was brilliant after his appearance as Marco in Talk to Her as another second fiddle, writer and sympathetic ear to heartbroken women in Talk to Her. Lorenzo feels like a continuation of Marco as he stalks her then stops because he recognizes that his understandable interest in Julieta’s sudden change in behavior is becoming unhealthy. He tries to be there for Julieta by occupying spaces that she traverses through while not violating her boundaries when packing her things.

In Julieta, people are driven mad for refusing to address trauma, living in the past or moving forward by erasing it instead of accepting it. Even though Julieta has an ambiguous ending, it is like life—uncontrollable, uncertain and open to many possibilities.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.