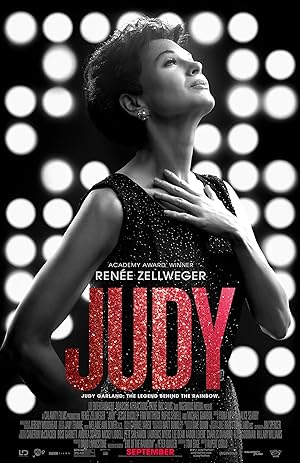

“Judy” (2019) stars Renee Zellweger as Judy Garland during a London five-week sold out concert months before she died. Flashbacks to her behind the scenes treatment during her child star days reveal the root of her later problems. Will she find a way to break the cycle? It is a film adaptation of Peter Quilter’s stage play, “End of the Rainbow.” While it is a biopic, the film distinguishes itself by using a superstar to model how parents can stop seeing children as existing to serve them and act in a child’s best interest.

I considered seeing “Judy” in theaters after glimpsing Zellweger’s transformation into the icon in a theatrical preview, but once I heard that Zellwegger woulsdbe singing, I tapped out and waited until it was available for home viewing. Director Rupert Goold intended to depict a singer struggling, not at her strongest point during her successful period as a Hollywood musical icon. If you are looking for a glossy biopic to evoke the same frisson that hit viewers when they first heard Garland sing, this movie is not for you.

The first act of “Judy” starts with Louis B Mayer (Richard Cordery), MGM cofounder, scaring a sixteen-year-old Judy (Darci Shaw) with two possibilities. She rejects the nightmarish thought of an ordinary life of a housewife with no way to use her voice, and no one remembering her—oblivion. She accepts a life of hard work, abuse and exploitation because of Mayer’s promise that she will get to use her gift, never be forgotten and be prosperous, but when we cut to her at forty-seven years old, that promise is a lie. She is homeless, singing for little money, unable to provide for her younger kids and uncertain of her voice’s reliability. When it opens, she and her younger kids are preparing for a life in the spotlight, but seem enervated, not energized. Will Judy unintentionally harm them and perpetuate the cycle of abuse?

“Judy” is a rigorous character study about how someone could save others even if she cannot save herself. It is about a woman struggling to figure out how to give her kids what she could not give herself. At the beginning of her journey, she only has them on stage with her so she can still have custody and watch them when she is working late. She is being the best mother and provider that she can, but she is still failing. In her first scene without her two youngest children, she drops in on her adult daughter, Liza Minelli (Gemma-Leah Devereux). In contrast to her mother’s life, Liza has friends, money, enjoys performing and seems to live the kind of life that her mother hoped to have. When Liza says that she has a show opening in two days, Judy asks, “How do you feel about it?….You’re not even a little anxious about it?” She is not trying to undermine her daughter’s confidence, but is amazed at it. In the rest of the movie, the film will show that Judy is the opposite of her daughter-exhausted from decades of work, riddled with nerves and daunted at the prospect of living up to her reputation. Judy does not ask Liza for help, but encourages her daughter to live a happy life independent from her mother, which is what a healthy parent should want for her adult children. It is the first sign that Judy is a good mother in spirit because of her willingness to let them go. The film’s momentum is directed at her working to financially provide the best home for her kids. She needs to leave them to make the big bucks elsewhere since opportunity in the US has dried up.

“Judy” uses flashbacks to explain Judy’s adult behavior so viewers cannot blame her for her desolate circumstances. When she flirts with a younger man, the flashback depicts her first date with Mickey Rooney with a twist at the end of that scene that underscores why she would not understand how healthy relationships function. Imagine “The Truman Show” (1998), but he knows that there are cameras everywhere. A stern woman chides her for wanting to eat the food on her plate and gives her a pill instead. For instance, later, whether having breakfast with her latest love interest or sharing a farewell celebration with her colleagues, she lacks the capacity to eat, but shows clear signs of having an eating disorder or just being out of practice regarding how to eat food since she received disciplined for doing so. The movie presents the challenges that handlers faced when trying to get Judy to meet her contractual obligations—like getting a toddler out the door. The subsequent flashback depicts that strict handler keeps feeding pills to Judy and ignoring a child’s plea of no longer being able to sleep. During filming of her sixteenth birthday party as a promotion—similar to how some New Year’s Eve celebrations get recorded long before December 31st, Judy finds ways to rebel and delay production when she is denied lunch and a bite of her birthday cake. Is adult Judy rebelling against decades of cruelty or being honest about not being able to function because she has not slept or eaten for decades? Is she aware that she will never get a break unless she incapacitates herself?

While the performances are not showstoppers, “Judy” chooses songs that reflect the titular character’s emotional state. The first song, “By Myself,” reflects her initial determination to leave her kids and everyone familiar so she can provide for them though she is not in any psychological or physical condition to do so. Because her worst day is better than most singers’ best day, she is on automatic and gets through her work night. “The Trolley Song” follows a flashback when she was elated after rebelling, but as the song continues, it becomes a montage of child and adult Judy plugging away at work with little to no breaks. The rapid pace is less about excitement and reveals a human body unable to sustain that grueling chuga chuga schedule with no genuine human connection.

The center of “Judy” shows how Judy is beginning to find her footing in this new environment and begins to cobble together a community. It is the turning point of the film. Will she succeed and escape the gravity of her destruction or will she get triggered again? While promoting her concert, she answers questions about her childhood and explains, “What matters to me now is my children’s happiness,” but when an interviewer notes that they are not with her in London and raises the possible toll of the custody battle, she winces as if she shocked. “If I’m this terrible mother that they like to write about, well, you tell me how I ended up with such incredible kids. Everybody suggests things like I’m not a real person…I’m only Judy Garland for an hour a night. The rest of the time, I’m part of a family. I just want what everybody wants. I seem to have a harder time getting it.” Things naturally fall apart—she lashes out and acts like an angry drunk during her performance. The next flashback reveals how she responds to discipline after getting chided for her mild act of rebellion. Back in London, it explains why she fawns after a disastrous night, out of fear that she will lose everything because she squelched on a deal and had a human, i.e. unprofessional, reaction. When she sees a doctor, he thinks that she needs rest. She responds, “At home with my children,” which the viewers know is impossible since she can only work away from her children.

Judy is lost, but there is a glimmer of hope in the next scene. Her next performance, “For Once in My Life,” is the soundtrack accompanying a montage of her performing, her love interest hustling to make prosperity and rest possible and Judy in her dressing room wistfully looking at photos of her children. A blow follows every high point so just when Judy believes that she can return to her kids, a person from the first act introduces the idea that maybe a reunion is not what is best for the children, but stability.

The final act of “Judy” is about her struggling to accept this reality-her unhappiness is their salvation. She lashes out and falls apart at work to the orchestral version of “The Trolley Song” accompanied by the crowds’ derision. It is a reprise to the first time that the song appears. Afterwards she goes to a phone booth and her daughter, Lorna Luft (Game of Thrones’ Bella Ramsey in a dreadful wig), breaks the news to her. Once the pressure of needing to work is lifted, she can socialize with her colleagues, eat food, and enjoy her talent. There is a flashback that punctuates this moment. Once the pressure to perform is absent and she is granted free time with Mickey Rooney, she chooses to continue performing to a live audience. Once she no longer obliged to work in London and stops hiding her vulnerability, she is eager to perform “Come Rain or Come Shine,” which is her unconditional love for singing for an audience. When the film ends, “Over the Rainbow” serves as a thematic bookend to the opening scene with Judy trying and facing her worst fear that her voice is done, but the audience carrying her with their voice. It is the happiest ending that can be constructed considering that she can never get what she wants: rest and her children.

While “Judy” creates a beautiful morality tale from a real person’s life, it does not mean that the depicted events reflect reality so never forget it is fiction. Minelli disavowed the movie. The movie depicts Sid Luft (an unrecognizable Rufus Sewell), Judy’s ex-husband, as the better alternative, but in real life, Luft admitted that he was complicit in feeding drugs to Judy to keep her functional. There were allegations of physical abuse. He is not necessarily a better alternative, just the only other one. These issues would complicate the self-sacrificing happy ending. Mickey Deans (Finn Wittrock), her last husband, is depicted as a man in love with the woman and her star power, but without staying power to endure the low point of her career. Judy’s disappointment gets weaponized and contributes to driving him away. The real-life man allegedly fed her drugs and stayed until the end. Healthy people did not surround a traumatized, dysfunctional Judy. Toxic people exploited and fed into that dysfunction to benefit from Judy.

“Judy” is a nuanced portrait of a flawed, gifted person with a simple lesson: parents exist for children, not vice versa.