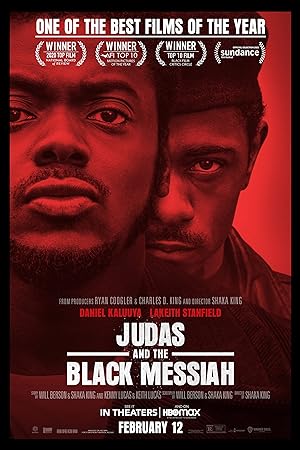

Judas and the Black Messiah are Biblical metaphoric references to respective historical characters Bill O’Neal, a car thief turned FBI informant, whom LaKeith Stanfield plays, and Black Panther Chairman Fred Hampton, whom Daniel Kaluuya plays. Overall as a movie, the narrative lacks focus, momentum or the ability to see the film from the perspective of a viewer unfamiliar with these men and this period. O’Neal is supposed to be an every man forced to rise above his personal concerns to act on a broader political stage with turbulent emotions pulling him towards survival and financial success yet constantly confronted with the possibility of becoming a better self, but O’Neal and most of the characters are underwritten, two dimensional characters, and LaKeith is never the most interesting actor in any scene.

The only reason to see Judas and the Black Messiah is to see the nuanced, superlative performances of Kaluuya, Dominique Fishback as Black Party member and Hampton’s love interest, Deborah Johnson, and Dominique Thorne as Judy Thorne, whose composite fictional character needed more scenes, and Alysia Joy Powell, who only appears for one perfect scene. Powell plays Mrs. Winters, the mother of a Black Panther member who murdered spoiler, and she tearfully says, “He did that. He did that, but that ain’t all he did.”

Judas and the Black Messiah should have taken her tearful line as literal guidance for their movie. Kaluuya, Fishback, Thorne and Powell transcend the limitations of the script and infuse an emotional history and character development missing in the actual script. Either the writers should have consciously made the focus of the movie characters as an ensemble, strictly focused on O’Neal and Hampton as a foil character study or just focused on Hampton, but for the first two possibilities to work, the characters needed to be fleshed out more on the page because not every actor should have to elevate the material with their performance. For instance, there are two minor characters whom we are supposed to care about, but until those two characters did something flashy with their gun, would you remember them? What made them stand out before that moment? You do not need a lot of backstory to get viewers to invest in minor characters, but you need something.

For a major character like O’Neal, he exists in a vacuum. He does not truly exist as a three-dimensional person before the FBI ensnare him or outside of his cover life as a Black Panther security official. He had a family. He presumably had a life which he was funding with his stolen car proceeds yet we have no sense of him as a person. Judas and the Black Messiah thinks that his trickster ability to put on whatever persona is required for that moment is sufficient, but this characteristic further distances us from him. American viewers love an unflappable conman, but to be equal to Kaluuya’s Hampton, we need more than chameleon abilities. We need an equally charismatic, magnetic core, which the writers fail to imagine and LaKeith’s acting limitations become apparent. His good looks and natural charisma only can take a character so far if his character has no backstory that at least he has brought to the table.

After watching Judas and the Black Messiah, I discovered that the filmmaker thought O’Neal was lying during his Eyes on the Prize interview and was thoroughly unlikeable, which may explain why the movie was not solid. They really wanted a Hampton bio pic, but could only fund production for a law and order story. In their heart, the filmmaker never saw O’Neal as a victim or the story as a tragedy. I would have preferred that they committed to their project or their beliefs, but the actual result fails to embody anything other than an entry point into the past as if O’Neal would have remained untouched and removed from all the excitement if the FBI had not recruited him. He may not have been in the inner circle, but by virtue of living in the neighborhood, he would have been affected to some degree. Why make a blank villain?

Similarly the FBI agents and other revolutionaries are one dimensional with the slight exception of Jesse Plemons’ FBI handler Roy Mitchell whom we see at home conducting business, but at least we know the demographics of his family and his work history. The FBI agents and revolutionaries are all business, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Only Hampton gets a personal life while alive, and I had a hard time imagining these characters existing independently to understand what brought them to this point. The best movies make me interested in the most tertiary characters, but most of the supporting cast were interchangeable until they interacted with Kaluuya, who is riveting as Hampton at his most dangerous—when he is building an alliance of unlikely groups.

When Judas and the Black Messiah finally explodes with onscreen violence, I wondered if the filmmaker was consciously unconcerned with or oblivious to the white gaze. A great film shows and does not tell, but this film relies on the viewer listening to Hampton and his potential allies discuss uniting against police violence and extrajudicial executions. The film depicts cops as a hostile occupying force, intimidating, harassing, but not explicitly instigating violence. Instead the Black Panthers are shown as the first ones to pull the trigger, which is Fox News’ fantasy come to life. If the filmmakers were tired of gorging on black pain and only wanted catharsis of the American vigilante story as described in I Am Not Your Negro, it does not explain the immediate, violent backlash against black bodies that is depicted once the Black Panthers hit first. Who does it serve to show black revolutionaries as instigators of violence instead of reacting to violence then immediately showing that violence swiftly punished? Why does this film consistently depict the police’s account as if it is the Black Panthers’ perspective when former real-life members stated the opposite? Is this movie really an afterschool special cautioning black people against even thinking about embracing any aspect of Black Panthers’ platform because it will ultimately lead to death? While not all violent encounters recreated in the film are entirely fictional, the first one was. If the filmmakers were aiming to show a love among members willing to sacrifice themselves for one person, surely it could have been done in a different way?

On the other hand, the real-life Deborah Johnson, now known as Akua Njeri, served as a consultant on Judas and the Black Messiah so if she is happy with the movie, what do I know? If Hampton’s significant other and son are happy then maybe the movie is brilliant, and I am too picky. I was on guard when the film started with my least favorite narrative trope, the how we got here trope, which begins with the end, the Eyes on the Prize interview, and a subsequent montage mix of archival footage and recreation which felt like a homage to Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman, an enjoyable but ultimately somewhat a self-indulgent, pleasing to the masses work that is not one of the best Lee movies to emulate.