This review was originally published on Roarfeminist.org

I am a self-proclaimed sports atheist. I’ll never watch Dr. Who because it seems insane to watch something that has existed longer than most people have, and sports definitely fall into that category. I like stories that have a beginning and an end. You can spend the rest of your life devoted to it and still never finish. I’m much too aware of my mortality to watch it and believe that it matters. Also everyone thinks that sports are objective, but my brief, childhood experiences in being a sports fan indicated otherwise. When I was a kid, I was really into figure skating, specifically the era of Surya Bonaly, Nancy Kerrigan, Katarina Witt, Debi Thomas and Tonya Harding. The women who were prettier or had better clothes won the awards even if their butts hit the ice because the mere attempt was enough. If you could do a back flip on ice, you may not make it. I didn’t need to waste my time watching ice skaters to learn that lesson. You could be the best skater, and if you had a bad day at the wrong time, tough, none of it mattered. It seems that sports demand everything from the participant with a disproportionate rate of return.

Even though I, Tonya is filled with humorous disclaimers, and the real life Tonya Harding may not have been as profane, there is something delightful about the dissonance of a woman athlete being as boastful and confident of her accomplishments as her male counterparts while forced to dress up like Tinkerbell. I bet that no film other than a period piece in which the female characters wear long dresses has there been as much incessant sowing in your life. We want ice skaters to look like princesses, but have the athletic prowess of Rocky. It is absurd, and the film is an implicit critique of gender norms, fame and law enforcement.

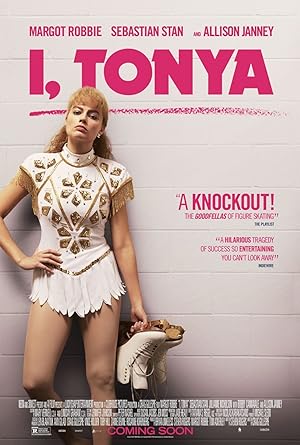

I, Tonya is so irreverent, fast paced and humorous that you almost forget that you are watching a tragedy, and there is no happy ending. Margot Robbie wisely plays her as unbowed, defiant and energetic, but none of it matters. She gives as good as she gets, but what she gets is a deck still stacked against her because of many factors that are out of her control: the amount of bureaucratic support athletes receive, abuse, socioeconomic origins, and family. Combined with quite a few questionable choices, any other outcome seems unlikely. It is part fate, predestination, not from God or the gods, but judges and part self-fulfilling prophecy.

Our nation offers athletes no type of support to discover and nurture up-and-coming athletes, but wants the international bragging rights. Russia takes it too far in the other direction, but the US lives in a fairy tale world in which the right people with a seed of talent and desire, as children or young people, will somehow self select themselves as candidates, find the right people to train them even if they are in a completely different region and financially, physically and mentally be able to devote themselves to an unlikely endeavor to be the best. It is the same fantasy that we tell ourselves about every profession, every talent and every outcome. Somehow amazing things will just organically happen without any planning or forethought. Then if they don’t succeed, which is likely because there can only be one, there is no safety net if you are not likeable. Endorsements are capricious. Education was probably sacrificed for training. Mental stability is questionable—people may praise the dedication and the self confidence, but you do have to be a little delusional or at least subject yourself to abuse, which may in turn cause mental illness, to attempt to succeed. Please tell me again how we don’t believe in child sacrifice anymore.

I, Tonya provides a triptych of Tonya’s options. She has her mother, perfectly played by Allison Janney. We like her because she installs Tonya’s fight and locomotive will, which is necessary to succeed, but she unapologetically knows that she is overshooting the mark. Janney’s performance is steely with enough subtle notes of regret and incapability of tenderness to suggest her own history of abuse that we never learn about. The mother treats Tonya like one of her exes who has left her with nothing as if she asked to be born, and the mother was not the adult in the relationship. She is Tonya’s Scylla, a theoretically once beautiful monster incapable of providing comfort and safety who will destroy instead of embracing.

Then Tonya has her coach played against type by Julianne Nicholson in what may be her best performance in a stellar year of supporting performances, which includes Novitiate. Her genteel, old school approach camouflages a toughness and wisdom that Tonya fails to appreciate and is unable to imitate. Unlike everyone else who is disturbed by Tonya’s manner, she is unruffled by Tonya’s bluster and is a perfect image of how to be there for someone while simultaneously withdrawing when necessary. Her honesty is not cruel, but professionally necessary; however she goes beyond her duty to help Tonya. She is probably the only good influence in Tonya’s life, and at the end of the day, she gets paid to do so.

Finally there is her husband played by Sebastian Stan. I, Tonya weaves a complex portrait of pathetic, ordinary every man and abusive monster. The film manages to create a sympathetic character without excusing or minimizing his behavior. The movie also subtly questions without explicitly sullying his character why he was hanging out at an ice skating rink with underage girls. He is a man who manages to gain entry into the pantheon, receives favor from the gods and instead of quietly appreciating his good fortune, lashes out in anger at his own idiocy, but strikes his goddess. In a sense, when the ice skating world originally and unfairly rejects Tonya, on some level, he vindicates their condemnation. He is Tonya’s Charybdis who consumes everything and shipwrecks her life.

Even though Stan and Paul Walter Hauser’s performances are superb, I, Tonya drags when it solely focuses on him and his gang of fools. The logistics of the crime and the takedown are necessary to fully grasp the story, but it does hurt the overall momentum of the movie. Robbie is the driving force of the film, and when she or Janney are not in a scene, that energy lags. While the actual skating scenes are well done considering that only a few women currently can execute a triple axel, and most of them are too busy competing to actually be in a movie, I watch too many movies and TV shows so I noticed the CGI face overlay of Robbie on the body.

I, Tonya blends the structure of Richard Linklater’s Bernie, the dark humor of Bad Santa and the understanding of Rashomon. If you enjoy the film, I would also recommend that you watch The Bronze, which Stan also appears in, and Foxcatcher, which have completely different tones and goals then read Joan Ryan’s Little Girls In Pretty Boxes: The Making & Breaking of Elite Gymnasts & Figure Skaters.