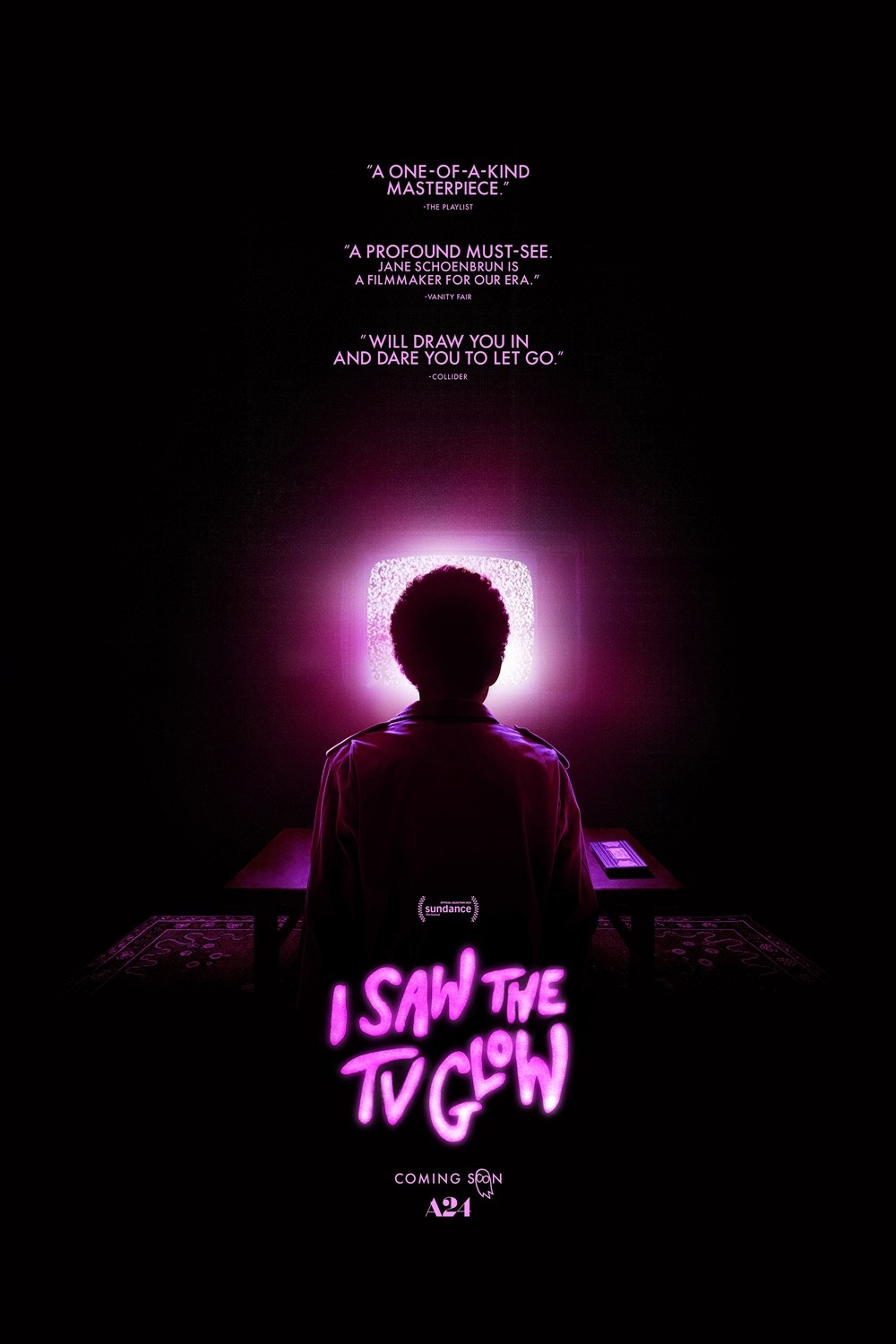

“I Saw the TV Glow” (2024) focuses on Owen (Ian Foreman plays the young teenager and Justice Smith for the rest of the movie) who is drawn to a television show, “The Pink Opaque.” When he sees the two years older Maddy (Brigette Lundy-Paine) reading an episode guide for the show, he reaches out to her, and she gradually reciprocates. As they get older, their reaction to the show diverges although their adoration for it only grows. She thinks that The Pink Opaque is real, and their suburban life is the distraction to stop them from being their true selves, but Owen disagrees, which eventually leads to their paths diverging. Who is right? Nonbinary director Jane Schoenbrun’s sophomore moody atmospheric film makes ambiguity satisfying.

Unless required, Owen is the kind of person who rarely interacts with people, speaks in soft tones and tends to be alone, but when he walks, he takes up space and marches down the center of a street, road or corridor, not trying to be invisible until it is time to relax then he goes to the lowest possible level: lying in the backseat of a car, curving into himself, hugging the margins. So, interacting with Maddy is more than a casual moment. He only talks to his mom, Brenda (Danielle Deadwyler, “Till”), to get what he needs to survive and limits interacting with his dad, Frank (Fred Durst, Limpbizkit), a pale, nightmarish lump of vacant flesh who bears a vague resemblance to one of the fictional TV show’s villains, seethes with disapproval and dominates through denial. Side note: another villain, Mr. Melancholy (Emma Portner), felt like another aalusion to “Le Voyage Dans La Lune” (1902), which “Lisa Frankenstein” (2024) reference. Through their autonomy denying rules, Owen’s parents sculpt Owen to be disproportionately childlike in comparison to his peers then Brenda is puzzled why she does not know him, and Frank wants a theoretical child who behaves in Frank’s predetermined appropriate way, not the reality of creating a real human being who may be something other than his parents envisioned. The parent child dynamic relationship feels almost as if they belong in a Yorgos Lanthimos film. Their befuddlement at the reality of their child creates a condemnation in Owen that haunts him.

Owen’s glimpse of a commercial for “The Pink Opaque” stirs something inside of himself and resonates to create a singular, elusive, largely unfulfilled, unexplored desire, which makes him determined to follow that thread: how to watch the show. “The Pink Opaque” becomes a Rorschach test for the suburban marginalized to find each other—much like “I Saw the TV Glow” will be to potential movie lovers. Talking to Maddy is not about teen attraction in the conventional sense, but recognition of members of an unofficial, secret club. For Owen, whom Schoenbrun shows as predominantly being alone, approaching Maddy is the equivalent of climbing Mount Everest, and she interests him because she loves the show too. Maddy is initially wary of Owen, but when she sees that her words wound him, she reciprocates, and their connection begins. She has her own wounds, and Schoenbrun alludes to Maddy’s abusive home life without becoming cliché or exploitive.

If you pay attention to the mythology of “The Pink Opaque,” you will recognize the parallels in Owen and Maddy’s friendship. For instance, in the fictional series, the dual protagonists, Isabel (Helena Howard) and Tara (Lindsey Jordan), share a psychic connection and only physically meet in the series once, which is like Owen and Maddy’s relationship. Because of his parents’ strictness, Owen only visits Maddy once before Maddy keeps the connection alive by supplying him with an ongoing series-run supply of VHS tapes decorated with show notes and details left in the black room for Void High School (yes, that is the name of their high school) with the occasional, awkward in person encounter. When they talk, it is from the sides, at an angle, around corners. They are soulmates like twins, but each encounter is tentative and furtive as if they are afraid of frightening the other away with the intensity that they direct at the series. They sit side by side with space in between them but moving in tandem with the series as their umbilical cord to each other. On special occasions, they face each other.: during their initial high school encounter on November 5, 1996, election day, then decades later, in 2007, as adults in a quotidian space that feels more liminal for being empty except for the two of them.

Only once does Schoenbrun choose to let the camera represent how they see each other: when Maddie proposes the wild idea of how to get back to their alleged true selves as the real characters on their favorite show. This head-on encounter is overstimulating. Owen is repelled because of the implications of her proposal. If the suburbs are real, then the pair is dying, insignificant, invisible. If they are the heroines of “The Pink Opaque,” there is a different, elemental death, a sloughing away of the familiar, a literal physical death necessary to emerge like a phoenix to their true selves, but a dash of madness and despair is a suicidal margin that leaves no room for error. Either option is crazy, imbued with too much teenage angst so when Owen runs away from Maddie as if she is the threat, it makes sense. Neither option is acceptable. There are some echoes of “Poltergeist” (1982) but “I Saw the TV Glow” is less a horror movie, and more of a meditation on conveying the existential crisis that tons of people feel in their isolated corners of the world that have no place for anyone who is different, cannot stick to the norms, felt suffocated and never felt at home with their family or in their native town so they had to run away or stayed and died slowly.

Owen and Maddy are queer characters. Maddy is a lesbian. Owen is different in ways that he never gives himself permission to explore. He does not look people in the eye (neurodivergent?). In a sliver of a scene, he permits himself a moment of muted joy by trying on one of Maddie’s halter neck dresses. He covers his hairy chest as quickly as possible with a heather grey short sleeve t-shirt, and in male drag, prefers oversized clothes that drape like dresses. Later he limits himself to his work uniforms and hanging out with his mean coworkers. Only once, with Maddie, does he venture to a venue featuring Sloppy Jane and King Woman with an audience filled with other potential Maggies to befriend, but he never considers it as an option without her. (It is not my kind of music, but if “I Saw the TV Glow” was a musical, it would work, and I’d buy the soundtrack.) The screams of the singers are portends of the suppressed rage within Owen.

Gender dysmorphia dominates more than sexuality though sexuality is touched upon. In response to Maddie asking about his orientation, he replies, “I like TV shows.” [Side note: substitute movies for TV shows and same.] Owen acts as an unreliable narrator breaking the fourth wall periodically throughout the film though he may be talking to himself. During one of these moments, as an adult, he is at his most disingenuous when he addresses the camera, “I have a family and love them very much” while clutching a LG (“Live Good” slogan printed on the front) box presumably containing a flat screen tv. We never see this family, and it feels like a lie unless the new sleek tv is said family. If it is the truth, Schoenbrun never shows them and only depicts what is truly important to Owen. He has become like his father, lying slackjawedin his living room with the television enchanting him and completely isolated from anyone in his household. He rejects Maddie to be alone, unable to imagine living a life that can measure up to his imagination.

Maddy talks about how time moves differently for them, which Owen denies, but upon rewatching “The Pink Opaque,” he discovers that the series is nothing like he remembered because his experience colored his interpretation of the series. The characters are younger with no people of color. The silver screen scenarios are brightly lit and more saccharine. It is a concept that Pedro Almodovar explores in “Pain and Glory” (2019): experience colors perception. In the denouement, time appears to stand still as no one moves around Owen or reacts to his actions as if he is a nightmarish dimension. He has zero effect on his surroundings as if he is moving in between the seconds like Quicksilver. Instead of using “The Matrix” franchise’s pioneering bullet time visual effect, everything else slows down. Schoenbrun shows how he exists in this world, but he is imperceptible to others even as he is finally willing to interact with others and be heard.

“I Saw the TV Glow” is original for its bleak underbelly. It turns on its head the concept of a teenager feeling special then following that thread until they get a bombastic confirmation. If “The X-Men” franchise had received the inoculation before their powers kicked in, this movie would be for the mutants who betrayed themselves or all the kids who had to run away from their hometowns to survive and those who stayed and died long before they were buried. While it may specifically have a trans meaning, the specificity of the experience makes it universally relatable to anyone who has ever felt apart and did not belong. If you did not like the movie, it could be because you’re the reason that people did not belong.

As someone who was in college and watched “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” in real-time, “I Saw the TV Glow” resonated and landed for me in a way that Schoenbrun’s directorial debut, “We’re All Going to the World’s Fair” (2021), did not though I deliberately decided to reserve judgment and rewatch their debut film before writing about it because I had a headache, and my physical state could have colored my reception of the film. Their sophomore feature has the potential to have the impact that “Everything Everywhere All At Once” (2022) had on so many. People were audibly sobbing at the Coolidge Corner Theater’s Breakthrough Artist Award showing of the film on Saturday, May 11, 2024 at 8 pm, and the majority of the crowd appeared to be cis gendered. Side note: in a stunning example of equity, Schoenbrun prioritized trans audience members so they could pose questions to the director. This film is going to touch people for capturing a mood.

Schoenbrun’s use of unnatural, eerie yet beautiful lighting and the spacing of objects such as upside-down circular tables or shopping carts outdoors makes everything seem off kilter as if it was not real life and a calculated placement to make it seem casual, but it is highly constructed. The setting seems harmless filled with noisy, colorful diversions such as theme parks or Fun Center so people do not notice that they are dying inside. If Pennywise jumped out, it would explain why these amusement spaces seem so sinister. It seems plausible that the real world would be the Midnight Realm, the underworld in “The Pink Opaque.” Smith, who had a box office failure in “The American Society of Magical Negroes” (2024), plays a similar, repressed, marginalized character, but his work here is stronger with fewer lines and a stronger story. Nonbinary actor Lundy-Paine delivers a memorable performance that cannot be dismissed as angsty, escapist teen or delusional person. They evoke a power that suggests they have more to give. There is not one bad apple in the bunch.

“I Saw the TV Glow” may not be for everyone, but it is the best film releasing nationally on May 17, 2024. Schoenbrun may attract more than studio money, but award accolades with this film. It is the kind of film that will be rewatched obsessively with closed captions on. At least, it will be a cult hit. At most, it will bring a wellspring of healing for movie lovers who did not even recognize that they had wounds.