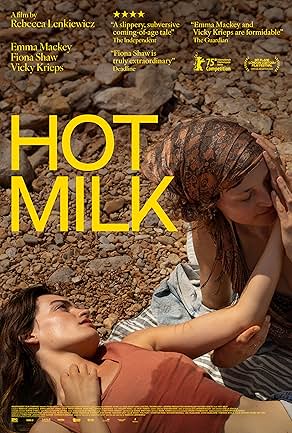

“Hot Milk” (2025) adapts Deborah Levy’s 2016 novel. Brit anthropology student Sofia (Emma Mackey, the brown-haired Margot Robbie doppelganger) is a liminal being with nothing that is solely hers and mostly stays silent. When Sofia takes her mostly immobile Irish mother, Rose (Fiona Shaw), for an experimental treatment with Dr. Gomez (Vincent Perez) at a sunny beachside town, her seething rises closer to the surface, and she begins to reach her breaking point. When she meets Ingrid (Vicky Krieps), a striking seamstress, it only hastens the process. Her needs emerge, and she demands that others meet them, a sudden shock to them after Sofia has accommodated them and abandoned herself forever.

The ensemble cast is pitch perfect, which is necessary to get the story from one point to the other with a deliberate lack of connective tissue throughout the narrative. Sofia does not truly ask for something until fifty minutes into “Hot Milk,” and she never gets what she asks for, but her demeanor suggests that she is sick of being the silent, taken-for-granted presence in everyone’s lives. When initially introduced, she is marching on the sand and ignoring the phone ringing. It is Rose, who incessantly talks or asks for help from Sofia. When Ingrid appears, a movie goer could be forgiven to expect that somehow her presence signals a seismic shift in Sofia’s life, a romantic partner who will change everything.

“Hot Milk” is not that kind of movie and rejects that trope entirely. No one is saving anyone, and individually, everyone is a bit of a mess and mystery to themselves. The first shot of Dr. Gomez shows him smoking. His daughter, Julieta (Patsy Ferran), an artist and nurse, can see Rose needs help, but Rose thinks that she may be an alcoholic. Gomez can see that Rose and Sofia should not still be together but obviously has not reflected on their daddy-daughter dynamic since he is the kind of employer who makes his daughter work on her birthday. Ingrid ends up spontaneously disclosing her past to Sofia, and it parallels her mother’s family history as much as it diverges. Under scrutiny, their stories become something entirely different, less or more provocative, always about secret sisters. There is no way to tell what is true and what is not, but when Rose starts thinking about trying new, more extreme treatments, it gives the impression of avoiding getting too close to the cause of her maladies. It also symbolizes her attempt to find a reason for Sofia to continue to be her caretaker. It does not take Freud to draw the link between Sofia’s dad, Christos (Vangelis Mourikis), leaving Rose when Sofia turned four years old, and Rose losing her ability to walk around the same time. After Sofia sees the beach’s rocks lined with jellyfish, and later a jellyfish stings Sofia during an ocean swim, diving into a swarm of them seems less like bad luck happenstance and more following in her mother’s psychological footsteps.

Surrealism does not have to be obvious or contain unreal imagery but can lie in the editing or writing. In one scene, Sofia buys a watermelon then goes in a public bathroom only holding her laptop. The watermelon later appears in her rental kitchen. Is it a goof? Is there a reasonable explanation? Sure, she left it outside the lavatory, but writer and director Rebecca Lenkiewicz, who wrote the screenplays for “Ida” (2013), “Colette” (2018) and “She Said” (2022), in her feature debut deliberately keeps us off kilter by creating subliminal gaps in her story. It is not important except that Ingrid is suddenly before Sofia in the bathroom, a wish fulfilled. When Ingrid suddenly appears at her window, “Hot Milk” is not a part of the “Twilight” franchise. How did Ingrid find Sofia? Sofia does the same with Ingrid the evening after Ingrid inexplicably turns up with their driver, Matty (Yann Gael), Ingrid’s boyfriend, to take them to Gomez’s clinic. Girlfriends do not usually tag along with their boyfriends on their workday. No explanation is given for any of these moments—not from Ingrid and not to the audience, but it makes sense without hearing them exchange addresses that they would innately know how to find each other. That attraction is not a solution to what ails Sofia.

Chaos cinema does not have to be shot with a shaky camera. Lenkiewicz uses measured composition, steady, still cameras and switching between close ups, medium and long shots. Black and white clips of classic anthropological films felt reminiscent of the tangents in “The Outrun” (2024). Sofia’s relationship to space and how she moves in show Sofia’s mindset more than anything. “Hot Milk” seems to keep throwing things at Sofia to see what will be the straw that breaks Sofia’s back, a woman who feels as shackled as the neighbor’s black dog who barks incessantly. Movies usually curtail the amount of time that an action actually takes to complete, so when Sofia decides to abruptly end a side trip to another country, she rounds the corner almost as if her return to the rental in Spain is as easy as going to the corner store. As Sofia starts to lash out against all the self-absorbed people who never consider her, there are no lasting onscreen consequences, but the characters react in shock. Sofia starts brandishing weapons, destroying people’s belongings and doing violent things, anything to disrupt being a supporting character in other people’s scripts. It is a provocative, daring and extreme way to carve out an identity. It is also unexpected for a woman protagonist to react that way without being dismissed as a crazy bitch. The world does not work like that. Like the branches on a tree in the movie, it is real and constructed, not organic.

In a world where Sofia is forced to be the audience for self-absorbed people who do not see her as an independent person, only in relation to themselves and her usefulness to them, Sofia’s journey in “Hot Milk” is to take the advice given to others, including the attention seekers in her life, or herself: “study herself,” “You have to ask yourself who you are,” “who you truly are,” “What would you do if I could walk?” The challenge is for Sofia to define herself in a vacuum without the benefit of being inside of one. When her love and attention are unreciprocated or thwarted, rage focuses this exercise of discovering herself. It is not surprising that many will walk away from the film dissatisfied. It is about an inner change, not something as pat as going to the US to study, getting the girl, finding comfort with new friends or family, which is how most conventional films would denote success. Sofia knows that she cannot stay the same, but just as Ingrid and Rose are still trying to work out their lives and failing, it is not going to happen overnight.

“Hot Milk” will improve with repeat viewings, but if you do not like films without a firm resolution, stay away because you will hate it and feel unrewarded. If you want to have a themed movie marathon, “Piety” (2023) is another film that also addresses toxic mother and child dynamics, hypochondria and projection. “Hot Milk” is the antonym to “Piety”: full of loose ends, messy nature and ambiguity with zero firm resolution instead of stylized, oneiric logic with a fully realized ending.