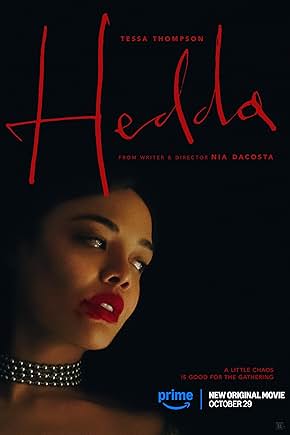

“After the Hunt” (2025) has nothing on writer and director Nia DaCosta’s latest and best film, “Hedda” (2025), a masterclass in race and gender bending in adapting Henrik Ibsen’s play, “Hedda Gabler.” Set in the United Kingdom instead of Norway and in the Fifties instead of the end of the nineteenth century, Tessa Thompson plays the titular character, a recently married bastard, biracial daughter of a landed gentry general who does not understand herself as she acts impulsively and manipulates everyone around her during a coming out party to ostensibly celebrate her nuptials. Her husband, George Tesman (Tom Bateman, who physically resembles Colin Firth), wants his wife to charm Professor Greenwood (Finbar Lynch), into getting him a job. What does Hedda want? Think scandalous and outrageous “Downton Abbey.”

I’ve never seen “Bridgerton,” but DaCosta comes up with the radical idea of Black people existing in the past, having advantages and just being people in an environment and an era that cinema usually renders invisible anyone not from the predominant caste. In this case, Hedda is horrible, but also delicious and great fun to watch. Black actors need to play the full human spectrum, even villains, without filmmakers falling into the well-worn, lazy tracks of racial stereotypes. While rooting for DaCosta, I have not been shy about pointing out the flaws in her earlier films, “Little Woods” (2018) or “The Marvels” (2023), while largely enjoying them or expressing complete disappointment in “Candyman” (2021). DaCosta needs to bottle whatever conditions led to “Hedda” and assiduously avoid anything that came before because whatever was holding her back has finally let go.

Of course, Thompson excels at playing a seemingly perfect character trying to adhere to heteronormative, neurotypical norms, but is really crumbling inside over her true desires and destroying everyone around her as a consolation prize. If you love her in “Hedda,” then you need to check her out in “Passing” (20210. Make it a double feature. Unlike the protagonist in “Passing,” Hedda is not passing, but for all her shocking antics, she is not living out loud. If someone described her as their crazy ex-girlfriend, they would not be lying though crazy would be reductive and derogatory. Though no diagnosis is offered, Hedda knows that she is not in control even if she seems as if she is, and DaCosta and Thompson reveal her fragility in silent moments. DaCosta frames and blocks every shot in the beginning to stress Hedda’s importance. Hedda dominates the first two acts.

Coexistence with Hedda is insufficient. These men are desperately trying to own her and take center stage, but they cannot. Though married to Hedda, George has a permanent scowl on his face, is constantly roughly grabbing her elbow and rebuking her as if he resents her. Just one look at his constant grimace, it is obvious that their marriage would be a more miserable affair if Hedda was in love with her husband. He wants to be her and is jealous of her. He wants a wife that he can ignore while she stays untouched on the shelf as he works, but he is intellectually dull and lacks creativity. Judge Roland Brack (Nicholas Pinnock, who played Jesus in “The Book of Clarence”) is constantly in the wings, and George seems clueless about his benefactor’s interest in his wife. He seems to enjoy their secret exchanges and would not want something more above board even though it was an option. It is only as the film unfolds that men stop being depicted as fragments, distant tenebrous figures or disembodied voices and start to share the frame, but they become more central as they try to overpower her.

Women are a different matter. DaCosta frames someone whom Hedda looks down on, Thea (Imogen Poots), a former classmate, on more equal footing, not as a fragment. Thea is an interesting foil because compared to Hedda, she decided to stop being a wife and become a writer, but Hedda bursts her balloon as Thea starts to use her maiden name. Hedda correctly notes that it is still her father’s name. Hedda seems free, but she is frustrated, suffocated that her existence is always male centered even if and when she defies it. Hedda is inherently problematic, but she is also nihilistic while conforming. Resistance is futile, but also what is the point of conforming and losing. It makes the ending more of a nightmare for Hedda, but her one moment of independence is rejecting last names, her father’s or her husband’s. She is the girl who has it all and nothing. It is the reality that Hedda is facing when Hedda’s former lover and husband’s current competitor for the same job, Eileen, instead of Eilert, Lovborg (Nina Hoss), reappears.

Everyone is citing director DaCosta’s Spike Lee homage when Hedda and Eileen first see each other, but how dare everyone miss that writer DaCosta fits in the dialogue, “Come on, Eileen.” You humorless, bitches! Let’s also give flowers to costume designer Lindsay Pugh who designed Eileen’s dress, which has a white cloth that wraps around her breast and shoulders, which gives a nude appearance, but also highlights her breasts, which becomes an active plot point. Think elegant Oktoberfest or Bavarian bar maid top, evening gown length. In their first time alone in a maze, there is a bit of a breast challenge with Hoss and Thompson leading chest first, not exactly touching, but pushing forward and dominating the other. It is this forceful movement that highlights their push pull attraction. In the third act, Eileen dominates once again chest first though unintentionally.

“Hedda” gives a glimpse of Eileen’s life in a male dominated atmosphere. While she is commanding, she is initially oblivious that some of them are treating her like a sex worker and enjoying the show. There is actually more chemistry between George and Eileen than George and Hedda. Honestly George and anyone because George is at his most hideous with Hedda. Hoss is a legend, and she is usually a sufficient reason to watch any movie. Her Eileen is a nascent sexologist and an open lesbian. Hedda is obviously so in love with her and is definitely a “if I can’t have you, no one can” girlie. Though Eileen is a more tragic, sympathetic figure, she is no dummy. Eileen knows better than to get in arm’s reach of Hedda or only have one copy of her book. If she has feet of clay, it is still needing male validation and desiring respectability.

There are other women who live freer lives though they may not get to be the center of attention. Kathryn Hunter appears in a cameo as the kitchen cook that knows everyone’s business or lack thereof. Another freer foil for Hedda is Jane Ji (Saffron Hocking), who wears slacks, calls Hedda on her crap and is just having a good time existing. She prods Hedda as much as she prods meeker characters, which is why Hedda is not a queen bee. Hedda does not really have a submissive clique.

For detractors who complain that it feels like a play, um no: the location, the chaos, the blocking. It tells a story. The story is dialogue heavy, but the line delivery feels organic. The suicidal ideation scenes, whether behind a frosted glass or just the hem of a skirt with rocks falling in pebbles, are cinematic. Also this hobgoblin demands consistency and demands that those better not be the same people into “Blue Moon” (2025), which I enjoyed, but felt staged.

“Hedda” is only playing on the small screen. Isn’t Emerald Fennell a gold mine? While less shocking than “Saltburn” (2023), there is a market for this! In Boston, if there was a screening or a screener available, I was not aware of it. It feels criminal not to see it in the theaters, but it is not an option so there is no excuse. Everyone with internet can watch it.