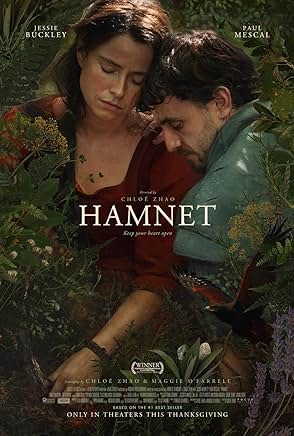

The less that you know about “Hamnet” (2025) going into it, the better. Director and cowriter Chloé Zhao adapts cowriter and novelist Maggie O’Farrell’s 2020 historical novel. Set in the sixteenth century, Agnes (Jessie Buckley), a primal woman who feels more comfortable in the forest and rejects the conventions of her time, meets her little half-brothers’ Latin tutor, Will (Paul Mescal), who has no practical prospects and lives with his head in the clouds. The two fall in love. They have a deep acceptance and understanding of each other until a tragedy drives a wedge between them. Will they find a way to reconnect? While relying heavily on emotional romanticism and too heavy handed for most, if you can allow yourself to be swept away, it is a fresh way to tell a well-known story, and the second 2025 film (the first being “Frankenstein”) that covers similar territory as an old Kenneth Branagh film, but does so in a more visually resounding and emotionally resonant way.

Visually “Hamnet” starts strong looking like Sir John Everett Millais’ mid-nineteenth century painting “Ophelia,” a pre-Raphaelite painting. The genre prioritized nature, expressed deeply felt ideas over conventional ones and wanted beauty to be realistic and spiritual. Zhao’s movie embodies all those principles with the imagery of the wild, verdant forest, dark natural caverns or tenebrous hallways leading to church sanctuaries, natural bodies of water, soaring hawks and lush gardens. These images take on wildly different meanings as the film continues, and the state of the couple’s relationship changes over time. Even the most joyous image retroactively is revealed to carry the shadow of death whether suicidal ideation or the threat of losing a loved one. While the entry point is a wild romance, it is also about finding a way to honor that love in death: not pretending that someone did not exist, not trying to forget them, not burying them without laying eyes on the dead or uttering any farewell.

It is not a surprise that Buckley fully immerses herself into the role of a wild woman who follows the family motto, “To live with our hearts open and to shut it not in the dark but to turn it to the sun.” Buckley never seems as if she is acting but performs in a visceral way. Agnes is one of her most innocent roles as the audience follows her as she experiences many firsts: the death of a loved one, love, sex and even being an audience member. It is such a raw and unself conscious performance that it is easy to mistake it as organic. Buckley does not just have chemistry with Mescal, but her scenes with Joe Alwyn, who plays her brother, Bartholomew. Bartholomew innately senses that marriage to Will, regardless of how much Will accepts her for being a wild woman, will be stultifying and tame her. “Hamnet” is a terrific sibling film as brothers fiercely protects their sisters from soul and literal death.

Mescal is well suited for this role, which plays to his strengths: being a bit spacey, mooney, lovey dovey and mournful. Will lives in the shadow of expectations, judgment and others’ reputation. Agnes becomes his unwitting muse and benefactor with the currency in the form of permission to be weird. There is a scene where he initially tries to court her in an acceptable manner, but when she scoffs giving him a look of ew, he tosses it and lands on being himself. It works, but the solution also becomes the problem as Agnes encourages him to follow his dreams instead of fit into the professions of his origins. The life of an artist becomes queer coded. If he does not get out of that provincial town, he will die.

If “Hamnet” has a glaring flaw, it is the disappearance of other failing fathers before Will has his first child. John (David Wilot), Will’s father, is an abusive fellow who plays favorites and is part of the reason that Will grabs on to Agnes like a life raft. Agnes’ father is a passive fellow who feels absent while in the room. In comparison, Will is killing it. He delights in his wife and children, thinks of them wherever he is regardless of what he is doing and imposes no expectations on the way that they navigate the world. This disappearance is noticeable because of how he cautions Hamnet (Jacobi Jupe) to stay away from his grandfather. It is a subtle way of showing a common truth: once a person has a child, a parent realizes how unfair their parents were when they abused them. His oldest child, Susanna (Bodhi Rae Breathnach), is more sensible and shows the influence of Will’s family, specifically her paternal grandmother (the great Emily Watson, who gets more to do here than her twin Samantha Morton in “Anemone”) more than Will ever did. Will makes sure to include Susanna when he is silly with his younger children, which includes Judith (Olivia Lynes). Will is credible as a good father because he is depicted as one wherever he is regardless of what he is doing.

Jupe may be the second coming of Nicholas Hoult. He owns the middle of “Hamnet” and delivers a seamless, rigorous emotional performance that sets it on its course for the second half. Now, if the name of his character, Hamnet, sounds familiar to you, then you know what this movie is about and where it is heading. He plays in some surreal, abstract settings to convey the mental turmoil of his character going through a process that most people cannot convincingly face, grasp then embody theoretically forget on cue and for an immeasurable audience. Hint: think of the beginning of “Jay Kelly” (2025). It works.

Costume designer Malgosia Turzanska’s styling of Agnes is obviously symbolic but also works. Her red and orange dress gives way to more muted, dull colors in the second half before restoring its course. Her wardrobe tells as much of the story as set directors Alice Felton and Ruthie Falconer as Zhao captures still shots of the home to show how the way it is occupied transforms as much as its occupants. It is a cinematic equivalent of a still life that matches the tone of the family’s psychological and physical state.

“Hamnet” is one of a series of 2025 films where a great artist chooses art over family though in this case, it is an act of survival and remembrance, not self-aggrandization. While less realistic than the glossy, luxurious “Jay Kelly” and less textured and nuanced than “Sentimental Value” (2025), the same art that saves Will and betrays the family also heals that family by showing the family that the artist actually does experience the same love and emotions even when not present then magnifies and transmogrifies those emotions into a creation that more people can relate to and empathize similarly. He makes his wife and children’s visions come true. This pain and beauty become elevated through magnification into something greater than it was on an individual, senseless level. It succeeds where the others do not by imagining a world where dads can have it all, the great, personally fulfilling profession without taking the “L” with his family. It works because it does not invalidate others’ feelings and finds a path to reconciliation.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Will is actually William Shakespeare. His wife inspires the witches from “MacBeth” and Ophelia’s flower references in “Hamlet.” The twins crossdressing influencing his comedies. His rebellious love story influences “Romeo and Juliet.” I wish that the marketing did not give away his identity and allowed moviegoers to either come to the realization or just appreciate the story if they were seeing it for the first time. His surname is stated in the last act, but hey. People do not read anymore. It is feasible that this latter category of audience exists, especially at a time when education just teaches to ace standardized test, and the humanities are scoffed at as impractical. The film loses a lot of momentum if moviegoers know what to expect instead of coming at it sideways and seeing it in a fresh way. Yes, it is heavy handed, but when everyone regardless of class reaches out to support Hamlet (Noah Jupe, Jacobi’s older brother), I cried a little. Imagine being an audience member for one of the greatest plays ever made and seeing it for the first time, and instead of being entertained, you see everything that you felt in the unfamiliar and thought was only an individual experience but is actually a universal and becomes communal. We kind of take it for granted with entertainment now, and we are a culture allergic to grappling with death. It worked for me, and I understand why it would not work for everyone.