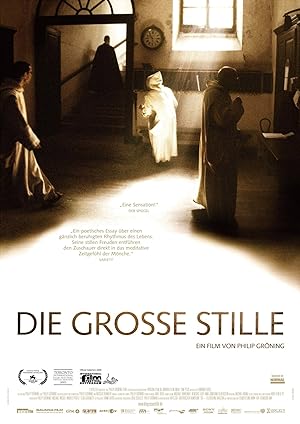

Into Great Silence is a documentary without narration and mostly without talking of any kind. It is 162 minutes long and focuses on the daily life of the men who belong to a French monastery. Either this topic appeals to you or not. It appealed to me so much that I waited until Friday night to give it my complete attention in a dark room, but I really regret that I did not see it in the theater. Even the slightest distraction like turning on the air conditioner or fiddling with the remote detracts from the contemplative nature, which Into Great Silence tries to impart in its viewers. I was able to give it my complete attention for two hours, but both sleep and technology conspired to take me away from the experience. Now imagine a life of devotion and complete attention to a simple life devoted to God in every aspect of daily life. In the last ten minutes, one old, blind monk basically summarizes the monks’ approach to life, which Philip Groning, the film’s director, used in his narrative: “In God there is no past. Solely the present prevails. And when God sees us, He always sees our entire life. And because He is an infinitely good being, He eternally seeks our well-being.” By watching Into Great Silence, you are seeing a glimpse at eternity and these monks’ entire life. The documentary provides no explanation why some monks are assigned certain tasks such as distributing food, feeding cats, preparing clothes, cooking. We have no idea what brought them there. They seem already part of the eternal or ever present in the way that they accomplish even the most mundane tasks or how they harmonize with their bucolic surroundings. It will make you think about your own daily life, and if you give such honor and peace to every aspect of your life. I found myself thinking of how being observed by Groning changed their eternal present life. The only sign that time has passed is the quality of the light, the changing seasons’ effect on the surrounding countryside and the signs of aging on the monks. The only reason that we know that we share the same world is the occasional glimpses of technology, tools that use electricity or glimpses of people who do not belong to the monastery. There are intertitles, some of which are repetitive, intercut with a few brief medium closeups of individual monks. There are volumes of symbolism in even the final still shots of objects as Groning moves the camera from focusing on a divided apple to bread. There were moments when the film purposely changes its quality-from high definition to something reminiscent of a 70s home film quality, which did not work for me. Into Great Silence is not for everyone, but if it comes to theaters, I would be first in line.