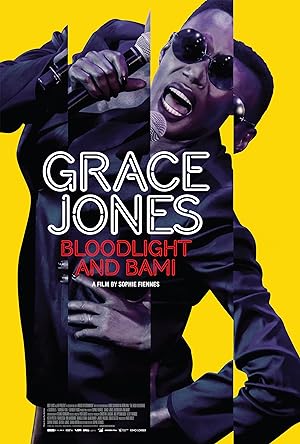

My first introduction to Grace Jones the model was my mom saying, “She looks like a man,” which I thought was a negative comment and interpreted as, “She has short hair.” My next introduction to Grace Jones the singer was in high school when a classmate danced to her interpretation of “La Vie en Rose,” which I thought was lovely and cool. A black woman sings a song in French-excellent. Then in college, I met Grace Jones the actor after I decided that Christopher Walken was the best and decided to watch all his movies, including A View to a Kill, in which I thought, “She does act like a man. She stole the whole movie.” I don’t even think that she had any lines, but she changed the entire energy of the movie. I’m sure that Boomerang was in the mix soon thereafter though less memorable for me because I don’t think that they appreciated her. Then she was hula hooping in concert, possibly topless. I can’t hula hoop now. Finally I heard that she was in a vampire movie, and she was the best part of the movie. I decided that it was time to get serious and instead of accidentally experiencing Grace Jones, I would make a concerted effort to learn about her and eagerly read her autobiography, “I’ll Never Write My Memoirs,” which I adored. Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami, a documentary by Sophie Fiennes, is the next logical step in my fangirling journey.

Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami is the second documentary that I saw, which Fiennes, the sister of Ralph and Joseph Fiennes, directed so I was prepared for something unconventional, i.e. without a linear narrative. It is an almost two hour deconstructed rock concert video/biographical documentary. If I was more familiar with her music, I think that the logic of the sequence of events would be more obvious. We see her performing then a personal or a professional scene that shows what either influenced that performance or made it possible. This film shows us what Jones is made of and how that becomes art.

I often read reviews that complain about PBS documentaries. I better not read reviews by those same people complaining about not knowing what is going on in Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami. It may not spoon feed you details, but it is discernible. Viewers will have to look for context clues to determine the location, the people and the nature of the scene, professional or personal. For me, I used the way that her voice sounded. Her voice is like a chameleon—it takes on different tones depending on whom she is directing her words. She also tends to mirror the accents around her. If it is deep, she is Grace Jones, the performer and public figure, commanding and dominant. If she is using an accent more than lowering her voice, she is trying to find common ground, to strike a deal. A more natural cadence denotes family or friends. When she seems manic, it is a different public persona, the partier, the one that can still go out to the clubs and act wild. She takes code switching to a new level.

If my mom, a woman who has only grown more conventional with age, could watch, understand and love Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami, and she was never into Jones, then I don’t understand what everyone else is waiting for. The performances are captivating and magnetic. The lighting and costumes can be elaborate, but only Jones can use sweat and skin as if it is the most simple, elegant costume change in existence. Fiennes shoots the film in such a way that it is rare to get a clear, center shot of Jones so it leaves the viewer hungry for more. My mom wanted me to buy the DVD so we could watch it repeatedly.

I think that viewers of West Indian descent will have an advantage over other viewers because Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami consists of a lot of footage of her returning home to Jamaica, hanging out with family and revisiting and recalling the past. The rhythm of the documentary mostly follows the meandering visit and pleasure of such trips that will be instantly recognizable to immigrants and their children, but puzzling to others. It is as ordinary and normal as Jones gets because it is a recognizable dynamic—surrendering to the family reconnection and recollection regardless of how it is structured. It is organic like a conversation, not an interview. The extras feature Jones and Fiennes at the Film Society of Lincoln Center discussing the film, and when Jones says that Fiennes is like family, I believe it because she captures those nothing moments that people take for granted and makes them the focal point. The only drawback of such closeness between the director and her subject is that it makes the documentary less approachable for acolytes. The film began to lose me after seventy minutes and maybe with a bit tighter editing, it would not have. A less familiar director is always better at conveying a subject to people unfamiliar with the subject; however Jones has never been for everyone so I think that if a documentary about her is slightly inscrutable, it is fitting.

Jones makes David Bowie, whom I adore (RIP), seem like someone who plays it safe in comparison. When a fan asks her, “Will you do another movie,” she responds in a deep rich voice that only comes second to Eartha Kitt, “My own.” For me, Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami felt like Jones’ version of Janet Jackson’s Control, and I was really engaged with those portions of the documentary. She knows what she wants, and everything else is in service of getting to that destination, but she is also an expert and professional who won’t take shit from anyone anymore. We’re following her as she is making her most recent album, and because she wants creative control, she is funding it herself, choosing the musicians, renting the studio and performing in certain venues to fund her album. It does not matter that she is an icon, she still has to deal with a certain amount of bullshit, and it is delicious to see her express her displeasure in a variety of ways: as a diva, a scholar (“We are visual artists. We know what things look like”) or as a scolding mother figure giving the best guilt trip.

There was only one moment in Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami that I met with displeasure, but Jones seemed unbothered by it. A photographer directs her by using the phrase, “monkey dance.” I immediately thought, “TF!” It turned out that the photographer was her ex-husband and son’s father so maybe I misheard or overreacted because it makes sense in some intimate context or maybe he is Jones’ blindspot. I don’t know. If you watch it and get it, please enlighten me.

I highly recommend Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami. It definitely made me want to see Jones in concert live one day or even contemplate rushing out to buy some of her music and blast it in my car. You need to watch the extras if only for random trivia about Blade Runner. Even when she appears to be loopy, she says some of the wisest comments that you can take with you for years to come. If you find Jones off putting or hate experimental narratives, run the other way.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.