“Good Madam” (2021) is about Tsidi (Chumisa Cosa) who decides to bring Winnie (Kamvalethu Jonas Raziya), her daughter, from “Gugs,” Gugulethu, to live with her mother, Mavis (Nosipho Mtebe) after a property dispute. Her mother is a live-in housekeeper in Constantia, a post-apartheid Afrikaner, i.e. white, suburb in Cape Town, South Africa, which triggers bad memories for Tsidi. Grappling with the loss of her grandmother and home, her resentment over her mother’s devotion to her employer, Diane, transforms into concern that there is a more sinister cause for her mother’s dutifulness. Are she and her daughter in danger?

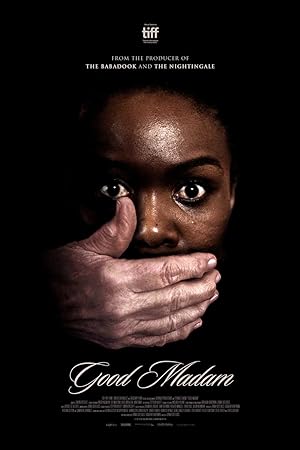

“Good Madam” has a predominantly African cast and speaks Xhosa though the occasional English phrase is spoken. The poster and cursive evoke “Us” (2019). Jenna Cato Bass, a white South African, directed and cowrote the film with Babalwa Baartman and Chumisa Cosa, black South African women. I am not South African, and this film was probably not made with Americans, even African Americans, as the intended audience so I know that I missed a lot of significance: Tsidi’s prayers, funeral ceremonies, the history of the country, innate knowledge of the specific locations, the featured songs—which I wish had subtitles, etc. There are flashes of some images that I did not understand: the washing of an animal head, a woman screaming in a room. While these images heightened the tension, in retrospect, I had zero clarity regarding their significance though I could guess. Is Tsidi vulnerable for breaking with tradition? So if you can find a review from an intended audience member, go for it then come back here for my uninformed take.

The best stories can also act as metaphors for real life horrors, and the house is a metaphor for South Africa. Though the house could not survive without black women’s existence and labor, they are required to make themselves subservient and invisible to exist in any space without being bothered. The family relationship and generational divides represent how each generation navigates colonialism, apartheid, and racism, but there was also an underdeveloped misogynistic theme that seemed critical to the catalyst sparking the film and the denouement. The financial precariousness of being a black woman is an emblem of misogynoir. Misogyny and racial discrimination put the black women at the mercy of others to survive. The backdrop of the horror is the reality of how the underclass must abandon their biological family while getting exploited and called family. If the underclass believes this lie, then the horror infects others.

Tsidi is underdeveloped though Cosa’s acting and the directing shows instead of tells her unspoken concerns. We have no sense of Tsidi’s life before her grandmother died. Did she just take care of her grandmother? Did she have a job? She mostly gets along with her ex, but why are they living together until they can land on their feet? It is fine if the filmmakers know and leave it unspoken; however, the film did not give that impression to me. Just naming her daughter Winnie evokes Mandela and an admiration for protesting school children, and her refusal to compromise in the face of patriarchy reflects an admirable stubbornness. By not exploring how Tsildi could be revolutionary, and yet her principles have failed her, it leaves an important element of the story untold about how post-apartheid South Africa failed those whom it was supposed to save.

By rejecting men’s imposition into her financial life, Tsidi and her daughter exile themselves from the black community, and they become minorities in her childhood “home.” When her daughter shows signs of preferring affluence and denigrating her township, Tsidi’s alarm is not over a disrespectful child, but an internalized racism that does not examine the cause for the disparity in conditions. Tsidi does not want Winnie to consider the wrong people family, which is fair, but the actual family is also problematic. Photos of her brother Gcinumzi, aka Stuart (Sanda Shandu), suggests that her concerns are realistic. Human sacrifice is metaphorical and literal through assimilation or violence.

Tsidi’s nightmare is becoming her mother, which seems unlikely considering how different their practical priorities are. She is also terrified of Winnie embracing whiteness and denigrating blackness. Tsidi finds common ground with her mother over their financial vulnerability. Without certain women in their lives, Tsidi’s grandmother and her mother’s employer, they cannot survive. Even though Diane is not visible for most of “Good Madam,” she is like a god who will know their transgressions without being present. Their culture and work are welcomed in the house, but their lives are not. “Good Madam” alludes, but never makes it explicit that Tsidi is understandably struggling with depression after her grandmother’s death, but no one recognizes and understands it. Instead she gets dismissed as crazy or lazy for not being functional or reacting emotionally. As her mother and Tsidi begin to spend more time together, Tsidi almost seems to get infected with her mom’s fervor for cleanliness while her mother loosens up.

While these themes are strong, “Good Madam” would have been stronger if it had followed through the story’s logic. The horror’s explanation is supernatural. Think “Hereditary” (2018) and old school zombies. Near the denouement, Tsidi casually remarks that she found a spell, which needed more hints prior to this announcement. I love the idea of the origins of this magic, and the purpose is to continue living in luxury during the afterlife, but it also has African origins. Why is this choice made? I love the mythology behind this spell, and to be fair, Europeans’ fascination with this ancient culture is well known, but how could they wield that magic? It plays into white supremacy to imply that this culture is not African since there has always been an effort to separate anything advanced and respected from its Africanness. Tsidi looks to her ancestors, specifically her grandmother, for protection, but for the opposition to wield a weapon from the home or at least neighboring team seems strange to me. While the appropriation is plausible, in a mythology with ancestors bestowing power, it feels as if there is a link that is missing. Also in the final shots, I was disappointed that the legacy for this magic was left ambiguous. It should not just stop with a couple of people. I would have preferred if the film made it more explicit that the seeds for this magic were disseminated beyond that house, especially since it seemed to reach back for generations. The fear of eternal slavery and exile from their people is a terrific concept.

Tsidi and Mavis’ dreams come true. Their happy ending may be considered controversial and perhaps like a horror story to those who do not empathize with their predicament. “Good Madam” does achieve what Lars von Trier clumsily tried to accomplish in “Manderlay” (2005), but “The Second Mother” (2015) succeeded at fully exploring the inherent conflict of being employed in a caring role and called family while not being treated like a member of the family and not being able to fully care for your flesh and blood. “The Second Mother” addressed gender and class, not race, so this film had more challenges. Like “The Help” (2011), it leaves white men off screen and clueless instead of culpable. It does not fully explore the other side of exploiting family—biological. While black men are depicted as complicit in exploiting black women in service for their own advancement, Tsidi’s faith in the concept of a biological family is unshaken despite little supporting evidence that she can rely on anyone after her grandmother died. For the horror to work, it needed to point to include the culpable.

“Good Madam” has a solid story, a great cast, and a gorgeous location, but the horror was more tentative than the subject matter deserved. The location, editing and directing build tension, but when all is revealed, the violence is too muted, especially considering the historical backdrop. The scares referenced classic horror films in which severed hands wreak havoc or hands act independently from their host’s will. It felt as if Ari Aster’s work was an influence, but Aster’s steady pacing and building of the mythology explodes and fulfills the promise of terror. This film never quite achieves that level of catharsis.