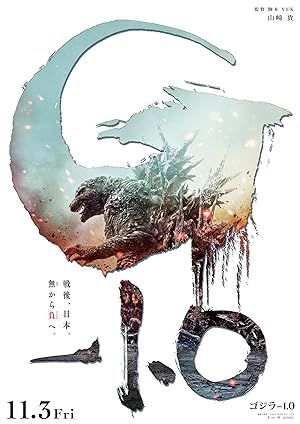

“Godzilla Minus One” (2023) is set in post-World War II Asia and follows Koichi Shikishima (Ryunosuke Kamiki), a former Japanese kamikaze fighter pilot who is disgraced and feels guilt ridden over choosing to obey his filial duty of surviving over his country’s orders to die for his nation. As Japan begins to recover, Koichi cannot move on and follow his heart by marrying Noriko (Minami Hamabe). When Godzilla begins attacking Japan, he finds a path to redemption and is determined to stop Godzilla so Japan does not have to fall into ruin again.

Japanese Godzilla movies were a staple of my childhood and a vague memory. I have not revisited them in adulthood nor seen the more recent installations. “Godzilla” (1998) starring Matthew Broderick was an utter disappointment, and “Godzilla” (2014) was barely a notch above though the subsequent MonsterVerse movies have shown some promise. “Godzilla Minus One” is critically acclaimed for a reason. It has excellent production values, has a majority Japanese cast and covers fresh territory by commencing during a time that has only been alluded to in the mythology: Godzilla was a dinosaur that mutated because of exposure to nuclear radiation. This Godzilla is thick. A friend with zero interest in seeing the film said that this kaiju has boobs, which is hard to unsee, but neglected to mention the giant thighs and butt. Godzilla is downright curvy, but objectifying this snowflake spiked overgrown lizard would be a mistake. According to the mythology, Westerners treat Godzilla like a monster, but Japan treats him as a destructive god. If they were describing Godzilla’s regeneration abilities, which renders the creature immortal, they are right. Equally intimidating is the laser-focused, red-eyed stare, which evinces a determination and focus that indicates brains backing Godzilla’s brute force. A favored feature is when Godzilla’s spikes rise and glow bright white blue to indicate when Godzilla is going to use their atomic breath, which has the effect of an atomic bomb though Hiroshima and Nagasaki are never explicitly referenced. The shockwave goes in and out like breath and wreaks complete havoc, blasting things away then sucking them back in. Godzilla becomes a sanitized, denationalized symbol of Japan’s conquerors in World War II-a chaotic, merciless death dealer. Godzilla’s attacks are random and undeserving, a force of nature, unlike the consequences of World War II, which were arguably earned.

Initially it seemed promising that “Godzilla Minus One” was set in post-World War II Japan. I overshot my expectations and thought that the film would grapple with the atrocities that they committed during that era, but instead it deals with the defeat and demoralization. Koichi is easy to like since he is insubordinate to a bellicose regime so it is hopefully unlikely that if the film rewound, Koichi would not be caught doing anything that should earn him a ticket to hell. He still feels guilty because writer and director Takashi Yamazaki is still Japanese, and everyone has a certain degree of national pride so he frames this disobedience as a failure to protect the defenseless when he has the ability to fight. (There would be no need to defend people if Japan had not become allies with the Nazis and started attacking people….) As Koichi rebuilds his life, including saving Noriko, he cannot enjoy it.

Noriko does not have a fleshed-out character. She saves babies, wants to live, and begs Kochi to confide in her. Yamazaki does a great job of showing that time is passing by showing the environment transform from ruins to solid structures, and the fashion changes from traditional to Western. When Noriko decides to get a job and wears a suit, it felt as if the camera treated her like the equivalent of Pamela Anderson running on the beach. In the end, her will to live becomes optional when Godzilla decides that he wants to take the same train that she is on, and she just appears to give up. Honestly same, girl. Same!

No one is going to save Japan. The US even rescinds demilitarization and says, “May the odds be ever in your favor,” because it is too busy with the Soviet Union. The Japanese government gets nothing but shade from its citizens, and the characters deride their government as secretive and unhelpful. So a rag tag bunch of navy veterans, now family men and one former kamikaze decide to forge a plan to stop an immortal. While “Godzilla Minus One” sidesteps the awkwardness of Japan’s role by slamming its government, it was a little troubling how easy it was to find battleships and fighter planes that were supposed to be decommissioned. Yes, one ship is officially returned to Japan (only for Godzilla to immediately destroy it), but the nation that raped its neighbors is not someone that you want hiding weapons two seconds later.

Yamazaki is using “Godzilla Minus One” to create an alternate history where the World War II Japanese veterans are not possible war criminals, but valiant defenders of people. The protagonist’s last name, Shikishima, happens to be the same as the Shikishima Squandron, which conducted the first successful kamikaze attack on the US. Ew. It comes from “Shikishima no Yamato Gokoro,” an Edo era Motoori Noringa’s tanka, a short poem, which is hung in the Yushukan war museum, which was built in the late nineteenth century, but honors kamikaze pilots in World War II. The poem reads, “If someone asks about the Yamato spirit [Spirit of Old/True Japan] of Shikishima [a poetic name of Japan]—it is the flowers of yamazakura that are fragrant in the Asahi [rising sun].” By erasing history as the aggressor and turning the Japanese into helpless, outmatched defenders, Yamazaki is getting the ordinary moviegoer, who may not even know about the horrors of the Pacific theater, to cheer for the Japanese to become a militarized nation again. By emphasizing their humanity against oversized, primordial monsters, human monstrosities are hidden from view. Japan has delivered inconsistent apologies for its torture of children and women whom they had the nerve to call comfort women, war supplies, public toilets, or female ammunition. Right wing elements in Japan try to suppress this history and claim it never happened. They even demand that other countries comply with their demands to take down statues memorializing their victims. If this movie existed outside of this push for revisionist history, alternate history would be understandable because not every movie about Japan must be a downer, but there should be some concern that our mindless monster movie may have a hidden agenda which outsiders are oblivious to.

“Godzilla Minus One” gets awkward as the narrative trajectory finds everyone rooting for Koichi to become a sincere kamikaze pilot again. Yamazaki deserves credit for finding a way that does not feel overtly Orwellian to reverse the essence of being a kamikaze in the twentieth century context without reverting to its origins, i.e. divine wind or used to describe a typhoon that scattered attacking Kublai Khan’s fleet of ships in the thirteenth century. Redefining kamikaze’s meaning is consistent with his rehabilitation of Japan by erasing history and feels like cheating, but as long as there is room for a sequel, which there is, maybe the next iteration will be less problematic so everyone can enjoy the monster mash spectacle in peace.

Postscript: A reader wrote a long, thoughtful counter to this review. I tried to contact them for permission to post with their name so they could get credit, but their email is no longer valid. Any way, while we disagree, I love that this reader felt passionate enough to write their own opinion and thought some of you may relate to this counter after reading my review.

Received on February 10, 2025 at 3:30 pm

“Hello,

I am writing to you in regards to a review you wrote a couple years ago for Godzilla Minus One. It was a very odd review as this story is a fictitious account of fictitious characters set during actual historical events. Takashi Yamazaki was in no way trying to recount real historical events. That must be made clear right away. However you made a number of statements that are quite troubling and some are incorrect historical facts. 1.) the assumption you make that all those who served in the Imperial Japanese armed forces at that time were apparently war criminals is incorrect. While it is undeniable that many committed unspeakable atrocities there were a fair number who never did. A couple real life examples are Ishiro Honda and Eji Tsubaraya. Both served in the Imperal Japanese army and witnessed awful war crimes but never committed any themselves. The characters in Minus One are not war criminals… the main character named Shikishima never saw any combat whatsoever. When his time came to be forced against his will to carry out a kamikaze attack he ran away. Side note: you also stated that his name is derived from the first Kamikaze squadron in 1945 this is also wrong. His name actually means, the Island of 4 seasons. Yamazaki was aware of this when creating his name. The mechanics his trauma stems from were just that mechanics. They never saw combat. His scientist friend created weapons for the navy but came to regret his contributions given the devastation they caused. There were other retired naval personnel but they would all have been confined to vessels not under their control. You seems very quick to generalize a very complex and nuanced historical situation that is not black and white. Were many individuals in the Japanese armed forces at the time war criminals? Yes, but not all of them. This would be much akin to saying all Germans at the time subscribed to nazism but this is also untrue.

2.) Japan in the film was not re-militarizing itself. At the end of the war little remained of their navy but 4 aircraft carriers existed but badly damaged, one battleship and two heavy cruisers. In the film the battleship they received came from the US to defend against Godzilla as they needed help. This is not Japan trying to regain military might it’s defending itself against a nearly unstoppable threat. Even the scientist said he wanted to stop Godzilla without using weapons. While the US had a presence in 1947 they wanted to avoid intervening with Godzilla as they would want to use Nuclear weapons which could provoke Russia. The characters understand this in the film.

3.) Takashi is not trying to revise history he wants people to realize that this film is built as an anti war warning and an anti imperialism warning. The imperial government and the armed forces are blamed by the characters in the film for landing them in their devastating situation. Innocent civilians always suffer the most out of everyone involved. This film takes aim at everything wrong with Japan at the time and it’s affect on other countries….

Here’s an alternative way to look at it. Should Captain America have addressed all the awful atrocities comities by US veterans at the time? Murder, rape, and destruction quite prevalent. Should Kong Skull Island have addressed the awful atrocities committed by US veterans in Vietnam? Neither of these films do, why is this because these aren’t characters who committed those acts Sarah. Just like Minus One, it doesn’t deny Japan did awful things but these characters were not apart of that. This is why we can’t view historical events through modern lenses as we will miss how society operated at that time. Life and death are viewed very differently in Japan in the 40’s. At the end of the film Koichi the main character flies a glider into Godzillas mouth to detonate the oxygen destroyer but he doesn’t take his own life he ejects and all his comrades beg him not to take his own life. Showcasing that the kamikaze way of thinking was wrong!

I have spoken with people who have taught history in Japan for years and say often their curriculum on WW2 is pretty solid especially today and if one pursues an education in history. I myself have studied WW2 history for over 2 decades and seeing this film highlighted important details while telling a fictitious story. This film is a warning to never return to the imperialism way of thinking. Please I implore you to do research on this subject and there are many novels on Japanese veterans experiences and there’s a review of this film by Gaijin goomba that also addresses this very well. WW2 was awful and it wasn’t black and white it was grey and very complex. Did Japan commit awful atrocities? Yup no doubt, but this film does not try to revise that or deny that. None of the characters were involved with that and stating there were normal men roped into a war they didn’t want who did not commit war crimes is not insane. If we view cinema through this lense how do we view Captain America or Kong Skull island as mentioned before? Food for thought

Thank you, only meant to clear up some very complex topics. Have a good day if you’ve read this far.”