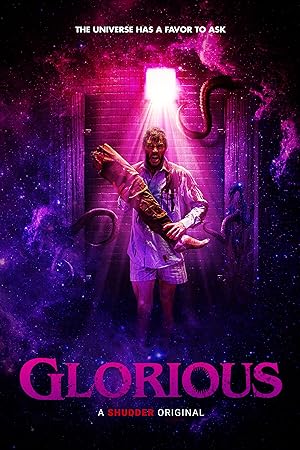

In “Glorious” (2022), Wes (Ryan Kwanten) goes on a dubious road trip and lands at an isolated rest stop where he goes on a bender. The next morning, while puking his guts out in a public restroom, an upbeat, enthusiastic, friendly, voice (J. K. Simmons) emerges from the neighboring stall and asks for a favor. As they get to know each other, Wes realizes that he cannot escape and the fate of humanity rests on his response.

If you enjoy Lovecraftian horror, you will enjoy this horror comedy. “Glorious” works because of the restrictive nature of the location, which is one of those great locations which are innately horrific and repulsive without the spectre of otherness. The limited number of players enhances the tension because it permits character exploration and provides room for gradual pacing until things start to go gonzo. Kwanten, who is best known as Sookie’s irresponsible big brother in HBO’s “True Blood,” is onscreen the entire time and must carry the entire movie. He alternates between being relatable and erratic without losing the audience’s sympathy. His bewilderment and volatility are somewhat off-kilter though he remains enough of an everyman that viewers will be invested in him emerging from this surreal situation.

“Glorious” succeeds in working on two levels. Either the Cthulhu mythos is real and has crossed paths with Wes, and/or Wes has gone insane after the end of a relationship. There are two mysteries to solve: the voice’s identity and what is Wes upset about. By the end, the film delivers answers. Most films will choose a side or cling to ambiguity while not making either story satisfying, but each story complements the other. Wes nicknames the voice Gath, short for Gathanothoa. Wes and Gath are excellent foils for each other though it is also possible that Wes is suffering from a mental break brought on by feeling a tumult of unfamiliar emotions and an inability to process them. They share similar origin stories and daddy issues, a desire to do good and transcend the limitations of their intended existence, a desire to belong and enjoy companionship while uncertain of their ability to break earlier patterns and nurture that microcosm of community. Gath keeps people away to protect them whereas Wes does not let people see the real him for other reasons. While Gath is more powerful and dangerous, Wes is more openly hostile and threatening, which is understandable considering the circumstances, but also an indication that he has more in common with Gath’s dad-enjoying isolation and lashing out at friendly overtures, which is the bare minimum necessary for community. Wes and Gath’s dad reject anything that reflects their true existence.

Regardless of which “Glorious” storyline that you choose to embrace, Gath serves as the voice of reason, an unusual Jiminy Cricket, a kind of therapist or older brother who uses this opportunity as an intervention so Wes stops running away from his true self. Wes and Gath are relatable because everyone can empathize with feeling unlovable and hiding away because of one’s monstrous nature. By the end, they come to terms with who they are, and while it is not exactly a happy ending, it is a peaceful and hopeful one. Wes starts with running away from himself and desperate for distraction to finding solace with his place in the universe even if it is not the highest goal that he had for himself. It feels like “The Mist” (2007) without the utter bleakness.

Rebekah McKendry, a professor at USC School of Cinematic Arts who is working on a horror reboot of “Bring It On” (2000), directed “Glorious,” and while I am unfamiliar with her work, I do not plan to be for much longer. She hits it out of the park. She defies George Bernard Shaw’s phrase, “Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach.” David Ian McKendry, her husband and frequent collaborator, was one of three writers, Joshua Hull and Todd Rigney. Even the best writing can fall flat without someone to visually translate the words onscreen, and McKendry, while not groundbreaking, is clearly a fan of the genre and pays homage with its color palette to Richard Stanley’s “Color Out of Space” (2019). Visually without any exposition, the film’s lighting and colors indicate when we are in the normal world or another dimension. She also has a wonderful comedic sense of timing by juxtaposing scatological humor with Simmons’ voice evoking grandiose cosmic expanse. Combined with Kwanten’s expressive face and physicality, it keeps the proceedings grounded, and the absurdity is hilarious.

“Glorious” has a long running joke regarding the nature of this favor, and the production design of the bathroom makes it seem probable however unlikely. It feels like Kwanten has resumed his “True Blood” role. The gloryhole is decorated with an illustration of a vagina dentata chimera of a woman seated on a trinity of skulls with a head made of multiple green worms with a gaping maw of black and bright red flesh encircled with eyes. Worm imagery appears as an image of decay infecting his memory. As other illustrations appear when Gath tells a story, more illustrations of unimaginable creatures emerge on the bathroom stall walls like moving cave paintings then disappear. It is a subversive Genesis creation story, but unlike other films with Lovecraftian ambitions, it never disappoints by reverting to Christian mythology tropes.

“Glorious” has one fatal flaw that may take audiences out of the film a little after the film’s midpoint. It adheres to one unfortunate horror trope, the identity of the only onscreen death. It is the only time that a character acts in an implausible way. If I heard someone screaming that they were stuck in a public isolated bathroom, I would not open the door without letting someone else know; walk inside without propping open the bathroom door or prevent the person from walking out. There is no way. While the film needed to deliver a well-earned shocking moment to make the threat feel credible and raise the gore factor, which it does perfectly, the victim’s identity undercuts the shock value of the scene. What a waste of a perfectly gorgeous shower of blood.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

The self-sacrifice of Wes’ liver is significant because clearly Gath can take as many livers as he wants. In a sacrifice, animal livers were used for divination. In medicine, the eater consumed liver for healing. Liver was considered the seat of life, love, soul and emotion, a symbol of courage and pleasure. Wes killed his victims by stabbing them in the liver area of the body though he did not understand the significance. After he stabs himself, while the penetration is violent and painful, the aftermath is also the closest image that we get to a hug, closeness, and intimacy, which suggests that Wes perceives normal affection as violent thus his homicidal tendencies. The wound acts as an entrance for Brenda and others’ hands into his body and Gath’s tentacle. The enormous stuffed bear as a scary monster with a bright red smooth stuffing matches his red safe box of souvenirs from his kills.

Wes is accustomed to hating humanity and unaccustomed to protecting people, even Brenda, the one that he began to love. Wes acts in character when he calls to Cthulhu even if it means the destruction of all life, including Wes himself. His appreciation of Cthulhu’s void explains why he killed Brenda and others. Like Cthulhu, he was startled when someone appeared in the void and reacted violently. The Polaroids of his other victims suggest a void behind them as well. He views kindness and love as frightening creatures. Wes is an unreliable protagonist because during most of the film, his perception is distorted except for Brenda’s photo. A serial killer would not mind if everyone died, but before when he realizes that Gath is going to kill Gary C., the black man, he does not want it.

Wes must use a broken mirror to cut himself (so unsanitary). The mirror forces him to face himself and punish himself. When he looks at Gath then at himself in the mirror, he sees his true reflection. “I look like death.” Instead he chooses to embrace his brief flicker of humanity, which does not erase his wrong doing, but enables him to accept the truth of his existence and accept that not everyone is like his worst self. He decides to save that part of himself by saving others and repents through self-sacrifice, which helps Gath to hide from his father and not become a weapon but remain a being that appreciates life instead of kills it. Wes saves Gath from becoming Wes forever. Gath becoming corporeal is symbolic of Wes giving into his worst urges. When a man finally plunges the knife into himself instead of others, which is what society asks women to do and encourages men to point the knife outwards, it stops the cycle of violence.