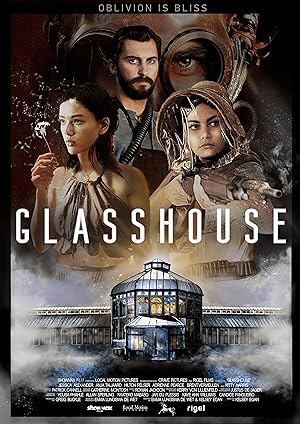

“Glasshouse” (2021), a South African film, takes place in a dystopian future after an airborne pandemic called the Shred makes people lose their memories and renders them almost nonfunctional proportionate to exposure and the age of the person. A family of five people, an older woman, two younger women, a young man and a little girl survive by shooting forgetters, living in a glass house, and tending plants that produce enough oxygen to survive. When one member saves a wounded stranger instead of shooting him, their routine gets disrupted, and the family is divided on his identity and whether the stranger can be trusted.

“Glasshouse” seems promising at first. There is not a lot of time between establishing their disturbing, but bucolic and picturesque quotidian life and introducing the catalyst that turns their world upside down. It is a visually beautiful film, and the cast does a great job. It is the kind of future where it looks as if people are returning to the past because without the numbers, there is no industrialization, so individuals must make what they use. The pandemic heightens the tension as a constant threat to the characters. I appreciated that the matriarchy was demented and not idealized, which is its own form of misogyny.

As the movie unfolds, each revelation in the form of gauzy, transmission interrupted flashbacks makes it duller. By the end, it feels a bit like “The Village” (2004), one of M. Night Shyamalan’s lesser films when everything is spelled out regarding how this family unit functions. I watched this film shortly after “Apples” (2020), and this film suffers in comparison.

“Glasshouse” has been compared with “The Beguiled” (no specifics on whether it is the original or Sofia Coppola remake). The reference makes sense because there are more women than men. Everyone reacts dramatically during every encounter and are more dangerous than they appear. There is no cannibalism, but their microcosm depends on killing intruders and using the body parts to sustain the plants and the house. Imagine a little girl excited to dissect a fresh dead body. A sword of Damocles hangs over every interaction because of this ghoulish contrast with civilization.

It is not long before “Glasshouse” reveals that it is not only violence that has become accepted. With the mystery over the stranger’s identity, and the taboo of incest, the film feels like a languid mashup of “The Imposter” (2012) and “Dogtooth” (2009). The pandemic makes everyone twisted, and sexual mores have changed. As double entendres become literal, the tasteful and voyeuristic sex scenes get tedious. There is no real nudity, but the movements and sounds are realistic. Sexual tension is critical to advancing the plot. Because this film came out after “Game of Thrones,” the incest feels in “Glasshouse” feels comparatively tame.

Even though women directed and wrote this film, and this unit appears matriarchal, it is hard to ignore that it still plays out like a male fantasy. A feminist film is not required to have women in solidarity who adore each other. There can be conflict, or all the women could even hate each other, but everything pivots around men-keeping them happy or deriving value from having a man choose you. The women work, and the men receive. The women are always gorgeous, and not a sweaty mess from all the manual labor. All the talk is about memory, but one could easily substitute any positive characteristic with memory, and the storyline would still work. There can only be one pretty girl. The woman with the most memory is the most attractive. This facet of the story becomes more obvious upon reflection. If I want to be generous, it is a matriarchal society where men finally get a say in their destiny because they were subject to the oldest woman’s decisions, but if being subservient means having sex and other people working while you watch, it is still a sweet deal considering the other options.

When “Glasshouse” starts, it feels as if the film’s sympathies are with the young woman who is more compassionate and rebels against tradition, not the one who obeys the older woman and accepts her role regardless of how demeaning it is. When the man appears, the latter gets flintier in her zealousness and suspicion. The movie gives the impression that she is jealous of her sister getting a sentient man, which is not the sole dynamic. The movie is sympathetic to the captive man, who is not permitted to leave because he is a security risk, but also cannot stay without diminishing their limited resources. As his role expands, the movie switches its sympathies between the two young women, and the rebel becomes an unreliable character. The film does a solid job of never villainizing a character and shifting perspectives.

However, when the stranger exercises his autonomy, the movie is devoid of judgment. Are we really cool with a dude banging one woman while courting the other? Because if we are, then the story did not bring me along. Just because it is Biblical does not mean that we should not question it. It is not that open of a society. In a world where people are rutting in the open, there is still monogamy and heteronormativity. Even with implied incest, homosexual attraction is absent. In a world with diminished mental capacity, the issue of consent is not considered. In our world, girls and women with mental disabilities are targets for sexual abuse. There is an implied rape by deception because of the man’s questionable identity, but that concept does not seem to occur to the filmmakers. It would explain the other sister’s outrage except the denouement undercuts it. Because the woman is happy, these are not issues.

The stranger’s questionable actions do not stop with his sexual activities. While his actions can be framed as merciful or in self-defense, especially in a dystopian world where it appears that the environment has collapsed, ignoring his obvious self-interest would be naïve. While depicting morally ambiguous characters and stories should not be equated with endorsement, it is hard to ignore that people unaffected by the pandemic end up on top. Disability relegates people to the margins or makes it permissible to execute them. While every society has flaws, especially in “Glasshouse,” the end reflects a society that feels fascistic. Regardless of mental capacity, women are baby makers, and only the healthiest men should breed. Identity is mutable. Illness can be treated with execution or further abuse. The hierarchy depends on usefulness reflecting what each character believes their society should value and preserve, but by the end, it feels a bit like propaganda for eugenics in a soft-core package. The only morality is that people with their memories deserve a life. It is ableist. The movie did not feel critical, but as if it was a happy ending, restoring balance and normality to the world.

“Glasshouse” did not work for me. It felt like a regressive fantasy of a dystopia, but for women who think that they are smart instead of sexy though everyone was gorgeous. It was great to see Adrienne Pearce as Mother. Pearce seems familiar and deserved more screentime. Otherwise the film left a bad aftertaste.