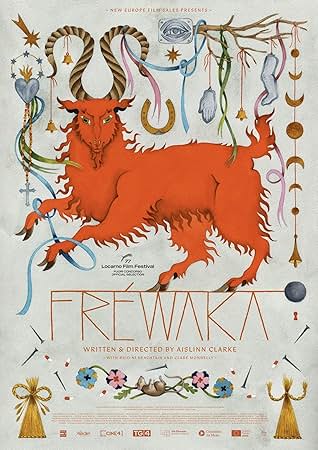

“Frewaka” (2024) is the phonetic spelling of the Irish word for roots, “Fréamhach.” In 1973, a bride (Grace Collender) disappears at her rollicking wedding reception. Today, a drunk woman dressed similarly commits suicide in her apartment filled with Catholic paraphernalia like crucifixes and statutes of the Virgin Mary. She is The Mother (Tara Breathnach) of Siubhán Ní Bhroin, nicknamed Shoo (Clare Monnelly), a student nurse planning to get married to her pregnant Ukraininan fiancé, Mila (Aleksandra Brystrzhitskaya). As they prepare to clean up her mother’s place on July 28th, Shoo jumps at the chance to work and get away from being near her mom’s place, which triggers her to imagine strange noises, movements and other phenomenon. Unfortunately, when she goes to take care of Peig Nic Giolla Blinde (Bríd Ní Neachtain), an elderly woman, with lots of superstitions, the environment exacerbates her symptoms. If “The Wicker Man” (1973) and “Carrie” (1976) without the powers had a baby in the world of “The Magdalene Sisters” (2002) sounds appealing, “Frewaka” is the folk horror movie for you, but it is a tragic tale.

Shoo, who wears an upside-down horseshoe necklace, is a woman who is pegged as an outsider, tourist or elitist, but she can speak Irish and is accustomed to be being pushed out, she pushes right back to be let in; thus, obeying the classic trope of ignoring the older man’s warning to go home. People treat her with open disdain and rudeness, and this place makes Hadonfield from “Halloween” (1978) seem like a welcoming place to neighbors and newcomers. The fact that it takes a long time for her to be phased at any strange goings on proves that she has seen a lot and thinks of red flags as a part of the decor. Mila pushes her to respond to her mother’s death in a normal way, but her lack of normal family relations is not a sign of lack of commitment but does symbolize how she is closed off from a support system and is unable to communicate with Mila, which endangers them. Her queerness is a nonissue, which was a welcome touch.

Peig starts off as an ambiguous figure and initially presents as a milder, but no less abrasive figure as the elderly woman in “The Front Room” (2024); however, she quickly becomes sympathetic though it takes her awhile to warm up to Shoo, whom she starts as openly hostile to. Shoo knows exactly how to handle her without missing a beat, but as she stays longer on the job, Shoo seems less stable than Peig, and they switch places. Peig tries to teach her to stop repressing her emotions and being deferential to authority but Shoo sees this behavior as surrendering to her mother’s madness.

Writer and director Aislinn Clarke thinks too highly of her audience because nothing is spelled out or explicitly referenced yet it makes a visceral kind of sense while simultaneously still leaving the audience feeling lost and grasping for answers thus putting the audience in the shoes of the three women characters, especially Shoo, the real protagonist. “Frewaka” works as a traditional horror movie and expressionist horror because initially it feels as if Shoo is afraid of inheriting her mother’s mental illness, and her experience makes her the perfect person to care for this patient, who is allegedly diagnosed with paranoia, dementia and delusions, but mental illness is only a symptom, not the cause of their ills. Clarke combines Celtic folklore with the Irish history of the Catholic church, especially with unwed mothers, as the backdrop and takes some evocative artistic liberties to flesh out the folklore.

I’m going to spell out my interpretation of the folklore, and then there will be a spoiler space to explain what happened in the movie. Technically explaining the folklore is in and of itself a spoiler, but I’m not an expert in Celtic mythology, just someone pulling a bunch of threads together. It may help you to enjoy the movie more whereas a spoiler ruins enjoying and discovering the story. Consider yourself warned and read no further if you consider the movie’s mythological universeto be a spoiler.

“Frewaka” never explains who the patient is referring to when she claims that a group kidnapped her but shows “them.” My theory is that they are Tuatha De Danann, Celtic gods predating Christian Ireland, or their descendants, fairies or the Sidhe. In the US, this mythology is new to us so points to Clarke for drawing on a new-to-us story. Forget everything that you may have learned in “The Watchers” (2024)—these fairy-like creatures have no wings and take the shape of human beings. The movie opens and closes on a verdant hill that can be accessed through a cellar door or “the house under the house.” This hill is probably supposed to symbolize the burial, elf or fairy mound associated with the sidhe. It is supposed to symbolize the Otherworld, which is under the earth’s surface. They can gain access to the human world at thin, threshold moments like weddings, births, deaths or certain holidays/festival times, which is the liminal place where Shoo lives now.

A person could inadvertently build their house on a fairy path, and a fairy tree is a lone hawthorn tree that acts like a boundary at a crossroads between the human and Sidhe world, a gateway to the Otherworld and interfering with it could anger the fairies. Proximity to the tree could put someone at risk for being taken. Removing anything from that tree could be bad luck. Apotropaic objects ward off fairies: metal like horseshoes or scissors, salt and urine. Urine wards off evil or fairies and protects women in childbirth. A mother’s urine is the most powerful. Mirrors can act like a gateway. In “Frewaka,” it acts as a portal to the past and forces people to relive and witness their trauma, which feels like a visual metaphor for PTSD, but the sidhe can also use it to enter. So covering a mirror protects against unwanted entry. Wearing clothes inside out is a way to break a fairy’s illusion. Smoke also repels fairies and disrupts the sidhe’s glamor because they allegedly hate bad smells.

If you know the Sleeping Beauty fairy tale, you will have a basic idea of how portentous it is to have uninvited visitors, especially if that visitor is a fairy, but it is not an explicit issue in Irish folklore. Loud celebration, specifically music, bright lights and unguarded joy attract fairies so to offset it, you leave food outside your home or place ribbons, milk or other items near the tree. The trick is to honor them without attracting their presence, but like changelings, they like taking people, but unlike changelings, they do not leave a substitute. This supernatural visitation is parallelled with the Magdalene Laundries which would enslave women if they got pregnant out of wedlock then separate the mothers from their babies. Even if a person escapes the Sidhe, they do not, which is the same as escaping religious abuse. The repercussions could last for generations.

Kidnapping a woman and taking her to the Otherworld has echoes in the Greek myth of Hades and Persephone but also forced marriage is a common trope in the fairy mythology. The woman can only escape during a fairy procession in the mortal world, but this movie departs a bit from this tradition. The supposed kidnappers take a couple of forms. They resemble wrenboys or straw boys if they were dressed to appear in “Reservoir Dogs” (1992): wearing black suits, white shirts and a straw headdress that covers their head. Wrenboys collect money, food and drink to bestow prosperity and bring unmarried people together, but in “Frewaka,” their appearance is sinister.

Another group wears red pants, and their torso leaves nothing visible as it is wrapped in a red outer layer and a white area that covers the head and torso. I could not find any information on the significance of this outfit. The look of brides, and the veil or headdress echoes the head coverings of these two groups but because the face is still visible, it seems less sinister. When The Mother hangs herself, she puts a sackcloth bag over her head, which resembles the wrenboys. A wrapped face feels like tools in a ritual where identity is erased. The Virgin Mary is often depicted with a halo, and in one scene, a bride has two golden hoops stuck in her hair that make it look like a crown or a saint’s halo but also could be a decorative piece to complement the horns of the groom.

A goat seems to rule over this realm and act as the new groom. The goat has significance in fairy mythology and Christianity. In Christian folklore, goats are equated with the devil or Satan. In Celtic folklore, the goat could be the púca, a shape-changer who can take human form with the head of a goat. They target humans on the road. If you ride them, they can kidnap you. A person can ward them off with metal, usually in the form of spurs, but in “Frewaka,” there is no riding, so spurs are not a form of protection as it is in the stories. While in the legend they can be good or bad, here they are a figure of dread. In Celtic folklore, the púca are not a part of the Sidhe legend so Clarke decided to mix things up to strengthen the through line between mythological abuses to historical ones. It also could be a reference to Cernunnos, but that god is a part of a Continental Celtic tradition, not Irish, or Pan/Faunus. If Clarke ever reveals what she was going for, let me know.

Haemolacria or hemolacria causes a person to cry blood. Hormones in fertile women, tumors or environmental factors could cause the condition. Bleeding eyes is evocative, and not specifically rooted in Sidhe legend. Being able to see the Sidhe usually means that the person already has second sight. It could be a literal manifestation that the person is seeing something so painful to look at that their eyes bleed. Because a human being is not supposed to be in the Otherworld, it could be a symptom of being there or seeing the goat headed groom.

The Mother sings the ballad of “Éamonn an Chnoic,” which translates to “Ned of the Hill,” a slow mournful ballad that Éamonn Ó Riain from County Tipperary in Ireland wrote. He was against British occupation. It seemed significant that a man with that name leaves a message for Mila on behalf of Shoo’s employer. Basically, he is separated from his beloved because of fear of retribution from the authorities because he is an outlaw. He and his bride did not get to raise their child, and Ireland is always under some form of occupation: Roman, British or Catholic.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

“Frewaka” is a film about epigenetic trauma or how your grandmother’s trauma is in the granddaughter’s body. When a pregnant woman experiences trauma whether at the hands of fairies or the Catholic Church, the fetus is exposed to the same conditions. When the fairies took Peig, she was pregnant with a daughter that her husband, Daithí (Mícheál Óg Lane), promised to exchange for Peig, but they cheated and had her adopted. (The hole in the story: the fae already had Peig so they could have just kept them both, but maybe she got married after she gave birth, and I missed that part.) That daughter would later become The Mother, and so many members of this family commit suicide. Peig figures it out when she rummages through a box that Mila mailed to her of The Mother’s belongings, which includes a birth certificate.

Shoo’s employer, Primary Care, never gave her a job, but the text and phone calls were from the fairies who tricked Shoo into coming to them to fulfill Daithí’s promise. The Sidhe can use phones to penetrate protected spaces. It could be argued that The Mother’s fanatic Catholicism could have served a protective function since Shoo links her mother’s compulsion with Peig’s use of apotropaic magic. The Mother made Shoo pray nonstop and locked her up like Carrie. It is almost as if the town already knows that and have a generational pact to sacrifice them like “Storm of the Century” (1999).

Apparently the fae are twisted allies because even though Shoo and Mina are not married, and that baby is not biologically related to Shoo, they are quite happy to take them instead of Shoo or were counting that Shoo would sacrifice herself to save them. It is like a tragic pyramid scheme because Mina begs for a trade that Shoo just made for her.