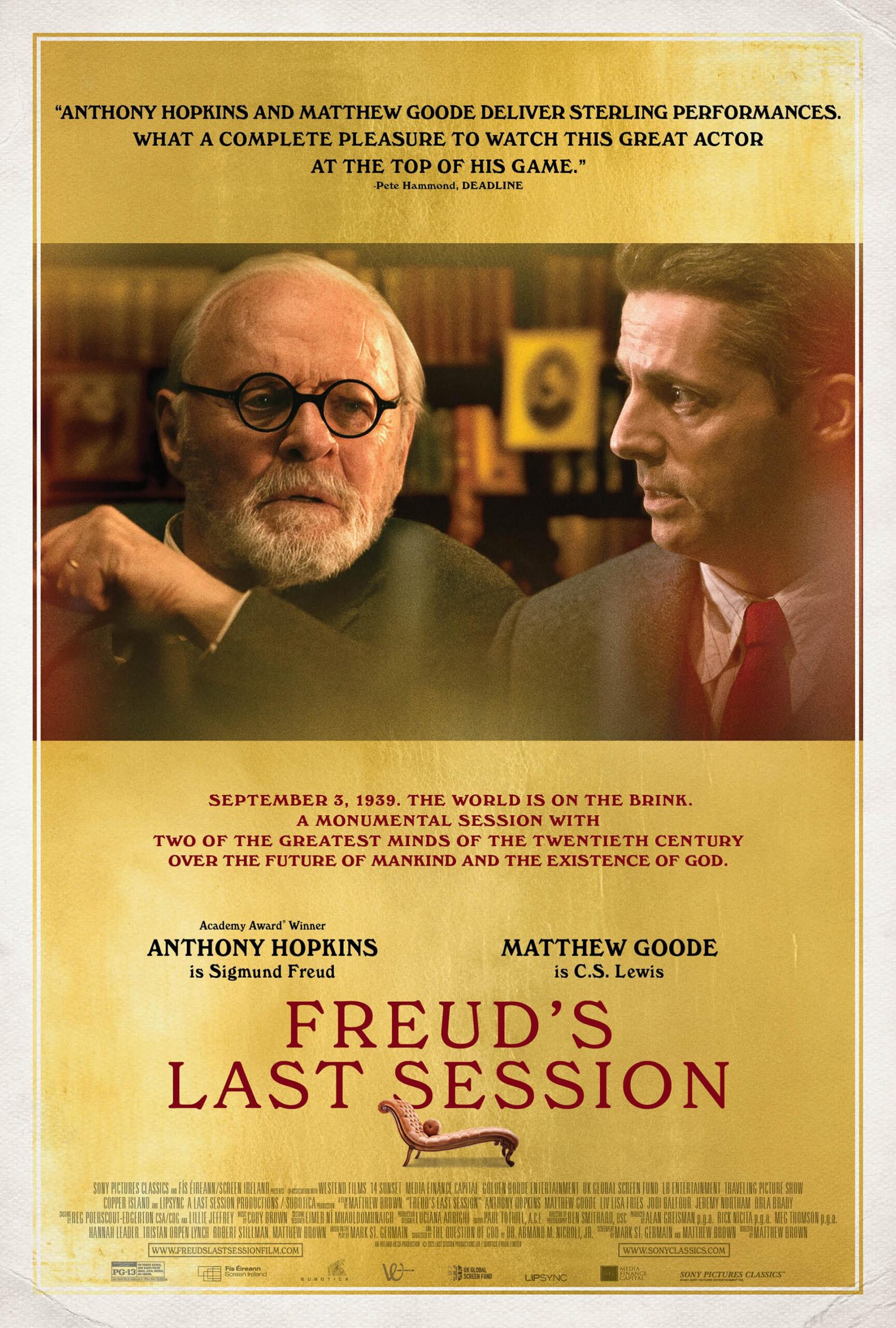

“Freud’s Last Session” (2023) is an adaptation of Mark St. Germain’s play, which is based on Clinical Professor of Psychology Armand Nicholi’s “The Question of God: C.S. Lewis and Sigmund Freud Debate God, Love, Sex, and The Meaning of Life.” On September 3, 1939, two days after the Nazis invaded Poland, the United Kingdom is getting prepared for war, and the streets and trains are bustling with activity. After extending a written invitation to C.S. Lewis (Matthew Goode), an ailing Sigmund Freud (Anthony Hopkins) waits for the Christian apologist to visit Freud’s home so they could discuss their beliefs. Despite misgivings about leaving her father alone at home, Anna Freud (Liv Lisa Fries) goes to work as a lecturer. Later that day, the United Kingdom declares war on Germany, while Freud fights debilitating pain, and Lewis tries to struggle through the triggers to his PTSD from World War I. Meanwhile Anna fights to find an open pharmacy to get medication for her father….no, she fights against her instinct to center her father and prioritize her happiness.

Sigmund Freud, the Austrian father of psychoanalysis, is approaching his twilight. He is open-minded except in his own life, especially when it concerns his daughter. He is an atheist, and his debate with Lewis is almost effortless for him in terms of intellectual rigor. He knows more than the parish priest about Catholic saints. Hopkins can make a meal out of a morsel, and while his delivery is up to its usual par, it is his physical demeanor that stands out in “Freud’s Last Session.” The indignity of illness makes him rely on Lewis more than he would at full strength, which breaks the tension whenever it mounts. At times, writer and director Matt Brown depicts one early flashback as Freud having moments of confusion and thinking that he is in the past. Later the two discuss their past, and the flashbacks depict the stories that they are telling.

Lewis’ buttoned up exterior gets shaken with the first air raid when Freud helps him calm down so he can enter the bomb shelter, which happens to be housed in a church. His reaction contrasts with his accounts of calm when discussing God. Goode is at his best when Lewis is not in academic debate mode and simply vibing with Freud or having any emotional reaction, but it was hard to imagine him as trusted professor Lewis considering his role as a dubious uncle in Chan-wook Park’s “Stoker” (2013) and other questionable roles, but considering that “Freud’s Last Session” does allude to Lewis’ freaky-deaky side, maybe he was the perfect person for the role. Also it is hard to forget that Hopkins played Lewis in “Shadowlands” (1993). If only there was some way for Hopkins to reprise the role decades later, which is impossible since Hopkins is in his eighties, and Lewis died just shy of his sixty-fifth birthday. It does not help that Lewis does not feel like the same person in each era: his isolated childhood (Oscar Massey), terrifying World War I (Padraic Delaney, who felt reminiscent of Barry Keoghan’s performance in “Saltburn” when his character flirts with an older woman) and the relatively peaceful 1939.

Watching “Freud’s Last Session” is like a buy two, get fifty percent off the third story. The individual stories would be worthy of their own movie, but somehow bundled together it seems cheaper. It often feels like its original structure. Lewis and Freud never met each other, but Nicholi put their written words side-by-side in his book as if they had debated the existence of God. Written dialogue from two highly educated men will never sound like more than a spirited, well-read book on tape, and I am a fan of Lewis’ writing. I spent years making sure that every other book that I read was a Lewis book. The concept of two icons spending the most turbulent day together sounds like a banger, but it is forgettable even while watching it. It sounds interesting to compare their childhoods and brushes with danger and war, but it stays remote and theoretical. The film should have stayed on stage, not converted to screen.

“Freud’s Last Session” has a more riveting pairing and conflict between the enmeshed Freud and Anna. Anna is the least renown of the three and the most interesting character in the film. She feels like a real person with a job, errands, commitments, and duties which clash. There is also a quick nod to the sexism that she faces in academia. Fries steals the show right from under two great actors’ noses and made me want to learn more about her. She goes on an actual emotional journey throughout the film and arrives a changed person by the denouement. Anna is an adult and a remarkable scholar, but she acts like her father’s devoted servant because of the importance of his work. Brown’s flashbacks become surreal, oneiric and downright Freudian when Freud describes a health scare. His waking dream reveals that he fears her sexuality, specifically she is a lesbian in a committed relationship with Dorothy (Jodi Balfour), but he sees her as a child. To survive the war and her father’s imminent death, she must embrace a life without him.

As the movie unfolds, everyone, including a high number of psychoanalysts, gets their analytical licks in with the father and daughter and call them out for their unusual relationship. All of Freud’s intellectualism flies out the window when it comes to Anna, and hypocrisy takes its place. “Freud’s Last Session” reveals how unethical Freud was because he served as his daughter’s therapist! Jeremy Northam appears as a possible paramour for Anna, but his character, Dr. Ernest Jones, is old enough to be her father, and Jones knew that she was a lesbian.

Unfortunately, there are more flaws in “Freud’s Last Session.” September 3, 1939 fell on a Sunday. Were classes held on a Sunday in the UK? A scene takes place in a church, and one of the most famous Christians ever is in a main character, but it is treated like a normal day. At least there needs to be a scene devoted to why Lewis chose to hang out with Freud over God, especially so close to war. Brown never conveyed the ecstasy of meeting God in Lewis’ forest scenes.

Is “Freud’s Last Session” approachable to people unfamiliar with Lewis? The Inklings are referenced, and thanks to J.R.R. Tolkien’s fame through Peter Jackson’s “Lord of the Rings” trilogy, maybe people know who they are, but it is a big ask. The story seemed promising when it is mentioned that Lewis and Freud are immigrants in the United Kingdom, but it is just an interesting fact never elaborated on.

Lewis felt shoehorned into a story that felt centered on the father and daughter dynamic, especially considering “Freud’s Last Session” could have been subversive with Freud on the metaphorical couch required to deal with his issues before he dies.