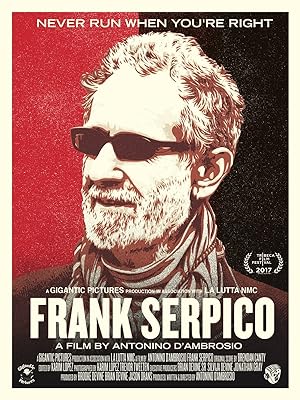

Frank Serpico is a well crafted, ninety-six minute documentary that is must see viewing for anyone who works for large institutions and must navigate the tight rope of allegiance to the institution and broader concepts such as justice, which shockingly may clash. If you saw Serpico starring Al Pacino, who clearly nailed the role, then you must see this documentary. It is more than just a biography, but a blueprint to living a meaningful and full life within a kakistocracy.

Eagle-eyed viewers will notice that the opening credits serve as a brief summary for the overall film, which is a biopic. Frank Serpico chronologically tells his life story and revisits important places from his childhood to now. The movie briefly diverts to commentary from friends, partners, historians, attorneys, literary agents, writers and filmmakers to provide an outsider’s perspective on the events that the titular figure discusses. Antonino D’Ambrosio does what many documentarians fail to do: gently challenges subjects’ views through the use of editing and juxtaposition. While D’Ambrosio is clearly on Serpico’s side, he also understands that no one can have an objective, arm’s length view on the significance and veracity of events in one’s life and may be oblivious to other notable factors.

While Serpico gets choked up when he discusses his Italian immigrant father as a former POW and his father’s work as a place of respite from the cruel world, Serpico never draws the explicit parallel of how he had no similar hesed, and his workplace was a source of psychological trauma and torture before he even got shot. Historians and cops who did not know him make this connection, which was clearly part of D’Ambrosio’s vision of Serpico’s life story. Serpico also theorizes that he became a cop to get justice for his murdered paternal grandfather, but another childhood story that he relays seems more pivotal to his life’s work as a person who seeks change within institutions. D’Ambrosio sees this story as integral to the immigrant’s story, the disillusionment with the American dream-not only that the image of abundance is false, but the reality is more primitive, one of scarcity and exploitation.

“What happens when you go into these institutions and discover it is a racket,” asks Italian historian Stanislao Pugliese. Peter Gleason, Serpico’s friend and a retired police officer, gives two options: be the Stepford Wife or be like Serpico, “But there has to be room for the innovator. So you’re no longer the ‘go along to get along’ kind of guy. That becomes very uncomfortable to the establishment.” If you’re like Serpico, then you believe in the ideals of the institution and try to expose corruption without hurting the low man on the totem pole who is also a victim albeit complicit in his silence. Donna Murch, a historian at Rutgers, stresses, “When you find people that don’t identify with power, they are very special. People like Frank Serpico that are willing to put themselves at risk. They’re important not only for what they tell us, but also the courage that they model for the rest of us. They remind you that you too can be honest and can speak the truth and confront power.” This courage comes with consequences.

Pugliese notes, “Institutions evolve and devolve in a certain way where corruption is absolutely unavoidable. The question then becomes how do those institutions deal with it then how does larger society deal with it.” D’Ambrosio’s documentary suggests that society deals with it by trying to crush men like Serpico instead of corruption, holding empty investigative commissions with no real solutions every twenty years to mollify the public whenever that corruption is exposed. Pugliese explains, “The system has ways of swallowing up these people-either you resign yourself, and you become cynical or you speak out, and the system destroys you.” So how does this institutional backlash affect individuals such as Serpico in the short and long term?

In a clip from an old interview, Serpico says, “I was a prisoner of myself.” There is a struggle between being aware of your outsider status versus instinctually acting justly without concern of the consequences, “Take care of it yourself!” D’Ambrosio uses commentators to explicitly describe Serpico as a POW struggling with PTSD as someone who tried to stop corruption, but also as an undercover cop fighting crime. “What they’re forced to believe is what they know is not the truth. There is nothing more frustrating than to tell somebody, ‘The sky is blue,’ and the establishment says, ‘No, it is green,’ then look at you like you’re crazy.” D’Ambrosio repeats certain moments with Serpico to depict how PTSD feels to the person suffering from it. There becomes a fracturing of identity: who you are versus what you do, expose corruption, and after a certain point, if you want to live and not become a lifeless statue, which is what Serpico chooses, he has to leave the institution and embrace life. Bob Delaney, a former undercover New Jersey State police officer explains, “Coming back to who you really are is difficult.” There is life after the institution and outside of it even though it seems unimaginable, but it requires a great distance and separation.

D’Ambrosio touches on Serpico’s broader cultural significance in the world of cinema, for Italian Americans and as a continued outspoken critic of the world of law enforcement, especially in the light of extrajudicial executions in New York and Ferguson. Throughout the documentary, D’Ambrosio highlights Serpico’s other gifts: as an actor, a photographer, an integral part of countercultural communities whether in the country, the city or the suburbs, inside or outside the US, as a conservationist. Serpico’s essential characteristic is as an independent thinker who has a dream of what an ethical, beneficial society looks like. Serpico is a contemporary vision of what our nation’s forefathers hoped that they would be, but failed to embody.

In contrast, Frank Serpico the documentary provides a foil for the titular figure in the form of his former partner, Arthur Cesare, a retired police detective, who is interviewed with Serpico beside him. Even though the men are cordial and initially delighted to see each other, it is obvious that even the part of the establishment that tolerated Serpico explicitly ignored his actions and words and the evidence, felt more outrage at his effort to attack corruption even if they claim not to be a part of it than the existence of corruption, which they ignored or forgot, and take umbrage with Serpico’s conclusion that the shooting was a direct consequence for his outspoken expose than an incidental hazard of the job. The whole exchange is increasingly uncomfortable, and the fact that Serpico handles this interaction diplomatically speaks volumes to his self-control despite others’ description of him as a loud mouth unable to suppress his outspoken views.

The final image of Frank Serpico, a nightstick as the clapper for a bell on his property, provides an evocative image of this whistleblower. Serpico’s following words should be our touchstone as we find ourselves immersed in a kakistocracy, “ We have to light the lamps that shed the light on corruption, injustice and abuse of power. Never has there been a greater need for lamplighters than today. One must hold our lawmakers accountable or democracy and freedom of speech will soon become extinct.” Murch correctly summarizes why we need to see such documentaries, “People have to see other people that have taken actions that made change in order to understand how to make change themselves.”

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.