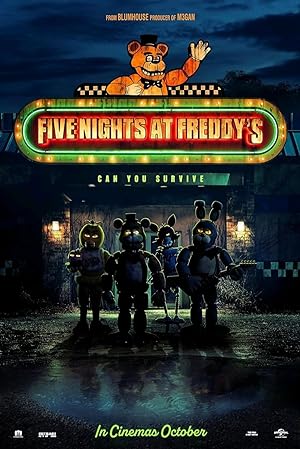

Set in the spring of 2000, “Five Nights at Freddy’s” (2023) stars “The Hunger Games” franchise’s Josh Hutcherson as Mike, an unemployed guardian of his little sister Abby (Piper Rubio), who accepts a night shift security guard position at the shuttered Freddy Fazbear’s Pizza unaware that animatronic mascots Freddy Fabear, Bonnie, Chica and Fox are homicidal kidnapped ghost children from the eighties with designs on recruiting a new member. With the help of Vanessa (Elizabeth Lail), a cop who patrols the children’s family entertainment pizzeria and thankfully never becomes a love interest, Mike tries to stop them before they kill again. The film adaptation of the pandemic popular video game that expanded into a multimedia franchise succeeds at pleasing newcomers and fervent fans like another crowd pleaser “Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves” (2023).

I debated about skipping “Five Nights at Freddy’s” because of its video game origins and the PG-13 rating, but horror is an inescapable lure. I did not know anything about the movie, but when I mentioned the movie to friends who are mothers and are not known for keeping up with movie news, I uncovered a widespread viral phenomenon that penetrated households more accustomed to loftier past times. So I went into the movie knowing that it was a big deal, but no further details, and if the movie was not good, I would have loved crapping on Scott Cawthon, who is rumored to be a Presidon’t supporter.

“Five Nights at Freddy’s” is a solid movie. A lot of scary movies do not feel like polished finished products, require Herculean suspension of disbelief, and leave tons of dangling threads and dropped plotlines. While the film had plenty of tropes such as the scheming Aunt Jane (Mary Stuart Masterson) trying to break up the siblings for the money, the film came together nicely because it had traumatized three dimensional characters, a meta sense of humor about horror movies and stellar acting, including from the child actors, especially Grant Feely, who played the Blonde Boy, tied together with an oneiric theme.

Elements of “Five Nights at Freddy’s,” such as children’s drawings and recurring nightmares, seem as if they are wallpaper or just psychological backstory, but they are pivotal to the narrative. Abby’s therapist, Dr. Lillian (Tadasay Young) tells Mike, “Images are the most important tool for understanding the world around us.” The heart of this story and the FNAF multimedia franchise shares this premise of choosing your preferred media to understand the horror around you and your place in it thus being able to navigate it and avoid repeating history. As the movie unfolds, these elements take central stage and expand. I have no idea if these elements are a part of the video game, but they are essential to the movie and elevate it from being like most video game movies into old school Stephen King territory—”It,” “The Shining”—with an inexplicable, overarching supernatural phenomenon that affects a region, but no one initially examines how it affects them individually or collectively.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

The supernatural affects Mike by giving him lucid, vivid detailed dreams, which can hurt him in the real world—“A Nightmare on Elm Street” (1984). This phenomenon is never discussed. He mistakenly believes that these dreams give him insight into the past, but they connect him to the present and permit him to communicate with the ghosts of kidnapped children. His encounter with them in the forest gave the vibe of “Doctor Sleep” (2019) and The True Knot. Meanwhile Abby communicates through drawing, but not just as a pastime or as a Rorschach test for her therapist to interpret, but with the same ghost kidnapped children. The ghost children and the animatronics function similarly: as lures to lure people into a dangerous location.

Mike dreams to erase past pain and find his kidnapped brother, Garrett (Lucas Grant), and Abby draws to imagine a better present social life with friends that she can play. The solution to their issues is to leave this dream world and be with each other. Fantasy opens a dangerous doorway that seems to solve their problems, but only endangers them. These animatronic mascots embody the duality of danger and diversion. They seem playful, but they sound like Terminators and resemble them with their glowing eyes. Proximity to Freddy Fazbear’s Pizza magnifies Mike and Abby’s separation and attachment to a dangerous desire. It is a liminal location like a haunted house, except no one ever lived there. It is distraction to attract and trap potential victims. The location becomes whatever you want it to be so that you stay and die instead of leaving and never coming back. The space seems to feed from souls. In many ways, “Five Nights at Freddy’s” is about the dangers of entertainment and allowing your imagination to distract you from reality to the degree that you are no longer in touch with the people that you love or notice the danger that you are in and put others in.

Mike is the first to recognize that by living in this dream world, he is exchanging a fantasy for his real sister. Once Abby realizes that her playmates want to hurt her, she taps out.

Freddy Fazbear’s Pizza’s animatronic mascots are the end result of what could happen to Mike and Abby, but are not the mastermind. I would even suggest that William Afton (terrific unsettling, out there performance) is not the mastermind as much as a serial killer who was going to kill kids and stick their bodies in an endoskeleton anywhere, but got lucky that he happened to be in an area where their spirits could be harnessed as energy to animate the endoskeleton and live on as an animatronic. “Pet Sematary” and “Poltergeist” (1982) territory! There is no indication that he was an expert in necromancy. It just happens. So there is something about the location combined with the energy of its inhabitants which fuel the phenomenon.

When “Five Nights at Freddy’s” ends, this phenomenon has not stopped. Abby’s drawing just awakened the ghost children from their being controlled with images. Images and entertainment are not inherently dangerous but are morally neutral tools that fall within a spectrum between good and evil depending on the person who uses them. Abby uses her tool to tell the truth about the past and uncover the source of their collective trauma thus breaking the power that Afton had over the ghost children.

If I am unsatisfied with “Five Nights at Freddy’s”, it never rises to significant levels. Afton admits to killing Garrett, but why did not Garrett become a ghost child? So no one is suspicious of Mike after the aunt’s murder? Who is Cupcake, a murdered pet? Actually maybe I don’t want the answer to that question. Cupcake’s ghost is not in the dream. Did Alton own the property? Which state does this take place in? It feels like the Midwest considering how spacious it is. Are we going to get a sequel? I’m game.