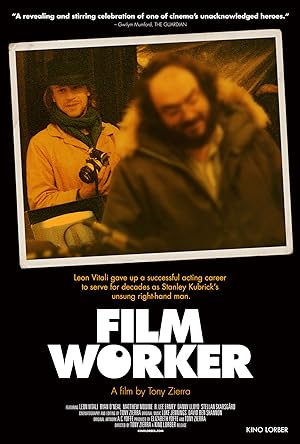

Filmworker, which has the subtitle within the film, but not when listed, Stanley Kubrick’s Unsung Assistant, focuses on Leon Vitali, who gave up acting to work beside Kubrick doing whatever he could to help Kubrick’s imagination become reality. I have probably seen all of Kubrick’s films, some more than once and consider myself an above average film lover, but even I think that this film is not for me, and I loved Room 237.

If you enjoy Star Wars and Elstree 1976 and you are a Kubrick fan, then Filmworker was made for you. This documentary is specifically for Kubrick zealots who watch his films repeatedly, specifically The Shining, Full Metal Jacket and Eyes Wide Shut, and could probably single-handedly recreate them with very little provocation. This documentary is less a biography about Vitali, which I would have preferred. The glimpses that we get of Vitali’s family are fascinating, especially how his father’s childhood experience during WWII (he witnessed Nazis executing his mother) created a mentally abusive home that made him perfectly groomed to deal with demanding father figures. I know that his waking hours were devoted to Kubrick, but I wanted to know more about his life away from work.

Filmworker delves into the minutiae of what he did for Kubrick: foley artist, casting director, editor, actor, producer, distributor, etc. Some of the actors involved in these films corroborate and reveal what it was like to work with Vitali and the crucial role that he played in their careers, specifically R. Lee Ermey. For fans of The Stand, Vitali basically shouted, “My life for you,” and Kubrick took that as a challenge, which Vitali always happily met regardless of the verbal abuse, long hours or unreasonable nature of their demands. The central question of this documentary is why would an up and coming actor sacrifice his career to work behind the scenes and get far less personal glory. I don’t think that we get an explicit answer, but Vitali believed in Kubrick’s genius and thought that his time and work would be put to better use in service to Kubrick than to himself, and he still does by guarding Kubrick’s legacy. He does his best still to act as quality control when people use Kubrick’s work or without compensation, devotes hours to Kubrick exhibits or talks about the great director, including this documentary.

For me, Filmworker acted as a jumping off point to explore themes of worth. Most people would not be able to do what Vitali did either because most people are incapable of such tremendous levels of self sacrifice in service to another regardless of how objectively great that person is. I also think that those same people theoretically agree with Vitali’s life choices. Why? Do not mistake my question as a question of Kubrick’s genius. It is not, but a question of who gets seen as a genius. I’m sure that there are many geniuses in film that do not get recognition or devotion. If you don’t get the devotion, then how can you do the amazing work if you have to also do the work that a Vitali would do for you? Do women or minority directors get similar devotees? Don’t you need such disciples to focus on making great work? Who gets to behave like a lout without receiving a backlash of quitting employees? There is an untold amount of energy devoted to social lubrication that Kubrick never had to worry about that people in a similar position who may belong to a demographic that normally is seen as the caretaker or deferential because of age, gender, ethnicity still have to care about feelings to a disproportionate extent. It is not enough to be professional, but there has to be perfection, no room to be human and show negative emotions or be labeled as a problem.

Everyone implicitly agrees that Vitali was crucial to great films, but he is far from financially secure. His work is not valued. He has no place in the film industry because he knows too much and can’t fit any of the film professions’ boxes. Without the genius’ name to hide behind, he becomes nobody. Objective excellent experience does not matter. He is too big to exploit, too knowledgeable to take a job in an area low enough for employers to feel comfortable to tell him what to do, but too low on the totem pole to trust like Kubrick. Americans like to pretend that we don’t have rigid class hierarchies, but we do, they are just more ambiguous and frustrating than other regions. Egalitarianism is a myth. No one would trust Vitali to make a film, and it is entirely possible that he has no desire to do anything but remain behind the scenes, but if he did, it would not matter. He is too great to serve, too low to rule, too unknown to keep Kubrick’s posthumous unofficial offer as his caretaker. Vitali is less perturbed by this snub than I am.

Vitali is a zealot who finds something that he loves and believes in then never lets go. I liked him as a person. My favorite Vitali quote was, “Do it until someone says no. Argue until someone says yes.” He recognized, “There will be no you,” but just because he made that deal with Kubrick, I don’t think that Filmworker has to uphold that agreement. I know that the reason that we are interested in Vitali is because of his professional relationship with Kubrick, but I don’t think that we should stop there. I wanted the documentary to be more about the whole man before Kubrick and on his off hours as few as they may have been.

Filmworker is not worth your time unless you are an obsessive fan of The Shining, Full Metal Jacket and Eyes Wide Shut while simultaneously being skeptical of films such as Room 237. I don’t think that it is enough to love documentaries that analyze films or explore filmmaking. This documentary is for a niche audience that even I don’t fit into, but it has value. It just wasn’t for me though I was eager to learn about the man behind the genius.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.