“Evil Does Not Exist” (2024) is Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s latest film, which was originally intended as a thirty-minute short film to accompany Eiko Ishibashi’s live score. Instead, the collaborators’ concept expanded into a feature length film. The film depicts life in Mizubiki Village before and after Tokyo developers hold a town meeting to get the locals’ feedback on a proposed glamping site mostly centering father, Takumi (Hitoshi Omika), and his daughter, Hana (Ryo Nishikawa). How will this project affect them?

It is best to go into “Evil Does Not Exist” with an open mind and knowing as little about the plot and characters as possible. In the first act, Hamaguchi introduces his audience to the denizens of this town, their habits and connections without a lot of explanation. Takumi and Kazuo (Hiroyuki Miura) are shown putting water in large containers to transport to an unknown location. Are they scientists testing the water? Do they not have running water in that town? Part of the reward of the film is just becoming attuned with Mizubiki Village’s rhythm of life and appreciating every aspect as precious. At a dinner with Kazuo and his wife, Sachi (Hazuki Kikuchi), and an older man, Suruga (Taijiro Tamura), Hamaguchi does not reveal if they are family, friends or associates. Suruga enjoys the feathers that Hana collects for him. Another dinner attendee, a young man with dyed blonde hair, fits in even though his appearance is rooted in this era. One relationship is clear: father and daughter are very alike and are more in tune with nature than people. Their heads are in the treetops with little concern about time or other human-imposed concepts.

The second act revolves around Playmode, the talent agency turned real estate developer, and their representatives, Takahashi (Ryuji Kosaka) and Mayuzumi (Ayaka Shibutani), who are tasked with pleasing authorities by checking off the box of meeting with the locals. Their canned responses and corporate jargon fail to impress these simple villagers. This part of “Evil Does Not Exist” shows the other side of the sweet and kind people in this quiet town. Their reaction to the developers range from polite firmness to physical hostility. The villagers are experts in their own lives, including their surroundings, and run circles around them until they are so humbled, the two beg their boss, Tamra (Yoshinori Miyata), to reconsider. The in-person meeting versus the virtual meeting is a contrast in humanity. Their drive to the village reveals details of the two representatives’ hopes and dreams. This portion of the film pairs wonderfully with the more frenetic, lengthier and realistic dystopian Romanian film “Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World” (2023) in the way that Hamaguchi takes his audience out of the villagers’ sense of time and deliberation and plunges us back into the rhythm of our quotidian lives through these representatives. It feels flat in comparison and though normal, a clear step down from village life.

During the third act, the two representatives, who are supposed to sway the villagers to their boss’ side, have clearly jumped ship and are swept away by the magic of nature and tempo of Takumi’s day. This act is also a reprise to the first act. Hamaguchi uses Takumi’s time with the representatives to explain what was depicted in the first act. Takumi allows them to shadow him and participate in his activities. While Takumi is effortlessly and wordlessly winning over the hearts and minds of the city mice, the effects of the presence of people like them will change everyone’s lives forever.

If you are not someone who usually watches foreign movies because of the subtitles, but are curious, “Evil Does Not Exist” may be the perfect film to start with. The dialogue is sparse and straight forward, so you do not have to worry about reading quickly. On the other hand, if you are not used to films where nothing flashy happens for most of the film, you could find it challenging; however, your patience will be rewarded with an abrupt tone shift and melodramatic development during the denouement, which has more in common with American films than foreign ones. Hamaguchi surprises by being a bit predictable if you are a seasoned movie goer and are accustomed to associating certain sounds and dialogue as foreshadowing.

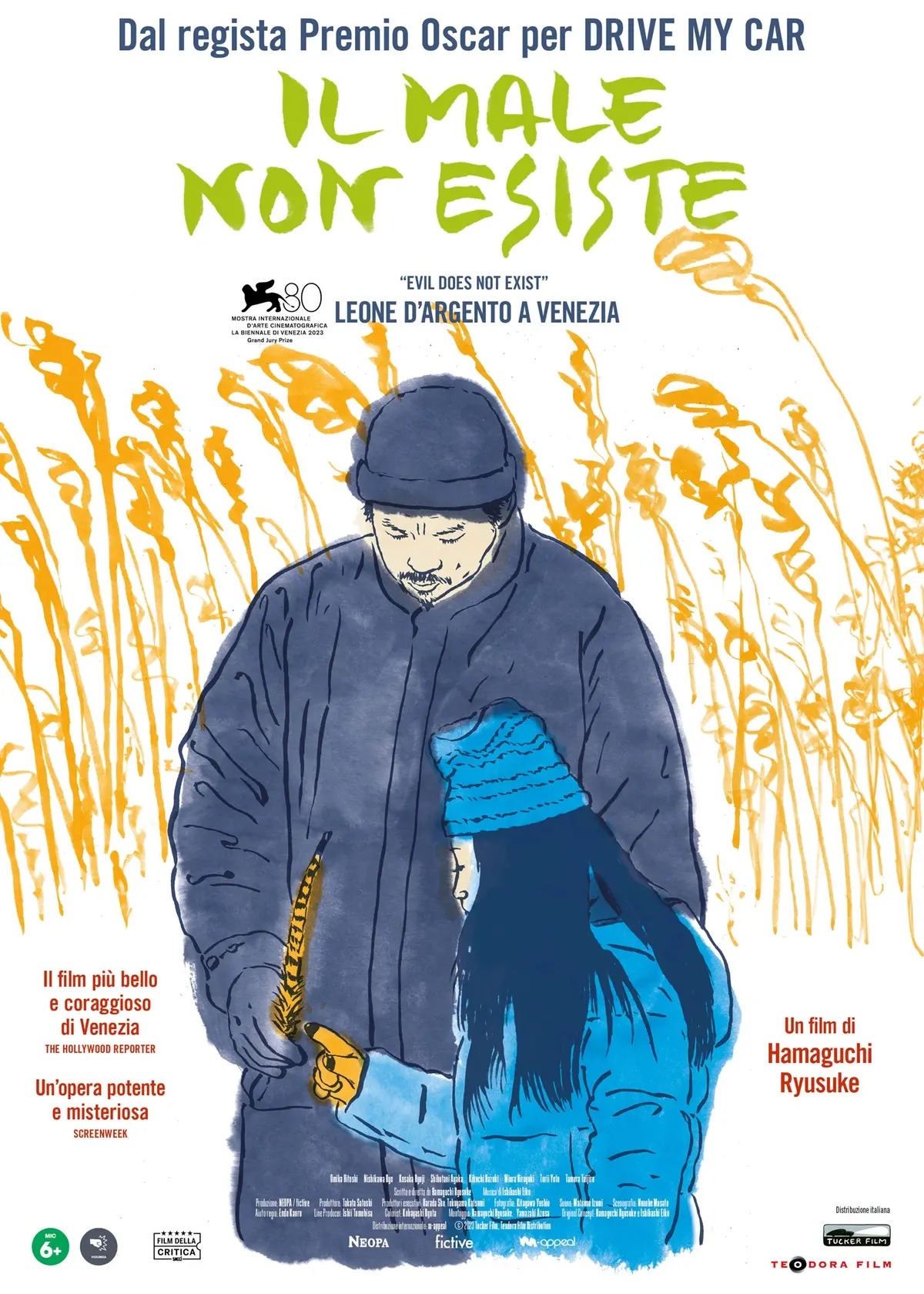

Without talking explicitly about the end, “Evil Does Not Exist” is a provocative title, and the title credits already give a sense of where it is heading. All the letters are in caps and colored blue except “not” is in red, a color not often seen until Takahashi appears in a red puffy jacket. Red is also the color of blood. In certain light, Hana’s gloves appear to be red, but they are another color. The father and daughter wear blue as do many of the villagers. When the words appear on screen, along with the opening credits, the words almost appear in random order. Blue is a soothing color, but is also a cold one, which can be associated with the snow. The sound of footsteps in the snow is important to the beginning and ending of the film with only the tempo changing. It may appear random compared to how credits normally roll, but there is a pattern though not obviously discernible.

In addition, there are parallels between the deer and the villagers. Both share a similar temperament and are in danger because of the development. In the first act, Hana exchanges a silent commiserating moment with them since she does not frighten them. They share similarities, but it would be a mistake to equate the villagers with the deer. During the meeting with the representatives, many of the villagers admit to being outsiders with an uneasy alliance to nature and admit that they have played a role in destroying it but try to achieve a balance. In a sense, all human beings are outsiders when it comes to an unpopulated area although we are also nature. The village originally consisted of settlers who were World War II vets, and many of the villagers would be descendants of those vets. It is a single line never elaborated beyond that note, but incredibly significant for an outsider who studies World War II. There is no way to know which character descends from that lineage.

This bucolic, peaceful village would be a huge contrast to the destruction and chaos of World War II, and during that time, the Japanese were the Nazis of Eastern Asia. Even before World War II, they were brutal colonizers. Unlike Germany which unequivocally disavowed any historical revisionism, Japan is still struggling with its history of committing war crimes and is currently going through its version of anti-critical history. So anyone who fought in a war would suffer a psychological impact and may not talk about it in that generation, but the added strain of being a part of a brutal jingoist death cult would likely increase the tension to readjusting to life at home, especially when raising subsequent generations. As a person who knew a woman who survived an abusive childhood with her Nazi high level official father, it is the first thing that I think about when I hear about veterans on the wrong side of history. That violence does not just evaporate because there are no acceptable targets. That violence emerges somewhere. Is any of this material discussed in “Evil Does Not Exist?” No.

Takumi is introduced using a chain saw from the point of view of the wood looking up at him. It is a tool which is not practical when committing violent acts against people, but cinematically it evokes horror movies. While Takumi appears to be a peaceful man, this introduction still feels shocking and counterintuitive. “The ax forgets, the tree remembers.” Editing creates abrupt transitions: from day to night, from score to diegetic sound, which includes the sound of distant gun shots etc. It creates an uneasy feeling and may remind people of Ari Aster’s films though it is comparatively a less dramatic transition. In the meeting, Takumi moves rapidly to stop someone who is getting increasingly aggressive, which means that he can detect aggression before it emerges and physically deflect it. He refuses alcohol, which could be a choice or a sign of a deeper affliction. Framed photographs of Takumi and Hana reveal a woman, who is never discussed. These are the ingredients that Hamaguchi is working with.

The ending of “Evil Does Not Exist” reminded me of “The Women of Brewster Place” (1989), a TV miniseries, which shocked me at the time as a child, but taught me a valuable lesson about human nature and fallout. There is always going to be a reaction to an action, but it does not have to make logical sense. When a primal instinct is triggered, proximity is the key.