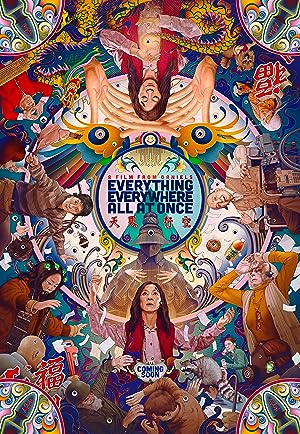

“Everything Everywhere All at Once” (2022) stars Michelle Yeoh as Evelyn, a Chinese immigrant middle aged woman reaching a personal breaking point. She is facing an audit of the family laundry business, her judgmental dad’s visit, her husband’s demands for her time and her American daughter’s emerging independent identity. Evelyn discovers that she may be the only one able to save the multiverse from a Big Bad who is closer than they think.

“Everything Everywhere All at Once” is a love letter to the cast and movies. Any filmmaker who casts Yeoh as the center of the universe has excellent taste. I have been a fan since her early days as a nineties, Hong Kong action hero when she appeared in such early hits as “Super Cop” (1992) and “The Heroic Trio” (1993). When her career moved to America, she was usually a supporting character in modest action roles. She still kicked ass, but the movie industry initially wanted to make her into a sex symbol as a Bond Girl in “Tomorrow Never Dies” (1997). As she got older, she began to lean equally on her acting muscle as much as her physical prowess, especially in films like “Crazy Rich Asians” (2018) as the memorable matriarch. Thanks to the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s Russo Brothers producing “Everything Everywhere All at Once,” the Daniels (Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert) put her back at center stage where she always belonged.

I am less familiar with Ke Huy Quan, who plays Evelyn’s sweet, silly husband, Waymond Wang, but “Everything Everywhere All at Once” appears to honor him too. Casting the legendary Jamie Lee Curtis, the ultimate Final Girl from the “Halloween” franchise, as a supporting character, is a great full circle moment where she gets to play an unstoppable antagonist. James Hong as Evelyn’s father carries the weight of decades of acting experience with grace.

“Everything Everywhere All at Once” uses sci-fi as metaphors for Evelyn’s life. Evelyn is a relatable character as a person being “pulled” in too many directions as symbolized by her jumps to different verses. Even as she casually devastates the people around her, the movie sympathizes with her plight. Her life did not go the way that she imagined, and she is working hard to fail at everything. She is at a crossroads. Does she just say fuck it, stick to her path or find another way to fight against despair?

The Daniels’ film may be a sci-fi action comedy, but it has the sensibility of an independent film that centers people that most of society overlooks or considers only in terms of how they benefit us—defined by their function, not their spirit. They plumb the pathos behind the laundry lady and make her the ultimate person, the best at failure or success, our best or worst. The multiverse becomes a metaphor for our lives, full of potential, hopes and dreams, achievements, and shortcomings. Evelyn landed here—no one’s idea of paradise, a soured American dream. Then the Daniels find a way to flip it and imbue that ordinary failed life as one full of existential despair or a possible paradise depending on how the characters confront their individual and collective crises. As the center of the family, its fighter, her redemption arc holds the potential to save generations and heal souls, but not until she recognizes her awesomeness and appreciates what she has.

Underneath the scatological humor and gonzo action, “Everything Everywhere All at Once” has a core of substance. The film is not weighed down with universe building but focuses on the emotional stakes. The goal is not to save the universe, but to rescue its characters from busyness, connect with themselves and each other and rescue them from despair. It takes the ordinary and simultaneously elevates it and makes it absurd. Waymond is the film’s beating heart and provides a countercultural image of masculinity. Quan plays Waymond not just as a goofy man. Waymond demands not to be dismissed-a silent rebuke to the industry for overlooking the actor and reclaiming and reframing the stereotype of the asexual or desexualized Asian men. He contains multitudes. He is an action star, a smoldering Won Kar-wai leading man and an ordinary man who loves his wife desperate for connection in a way that defies American gender norms, but embodies the best of masculinity. He is the actual Biblical Christian ideal of the man leading through love for his family, demanding more from his marriage, taking on a role that women usually play—carrying the psychological health of the family and the relationship. He provides an opposing way of navigating a meaningless world.

Waymond’s fighting is reminiscent of the most subversive season 5 finale episode, “Conquer” of “The Walking Dead” when Glen chooses life over self-defense. Kindness to enemies is not a weakness, but a counterintuitive act of defiance against a world with no mercy. The idea of fighting the Big Bad with kindness is subversive. “Please be kind, especially when we don’t know what is going on.” I was initially annoyed that he dominated the fight scenes in the beginning because I came for Yeoh, but given the narrative arc, it was essential and unexpected move. He is the anchor for the family in a tug of war between meaning and meaninglessness.

While “Everything Everywhere All at Once” presents a Big Bad as unstoppable as Thanos, the real villain is the threat of nihilism—looking at the world and only experiencing disappointment even when imbued with awesome powers and realized potential. “Vanity, vanity, all is vanity.” It is the classic Solomon problem. Going through the motions of life is exhausting when nothing really matters. While Evelyn fears that her life is a failure, the Big Bad is the epitome of success, which is more devastating in its emptiness and not being able to feel anything. The Big Bad’s origin story sheds light on one cause of these mental wounds, depression. The tragic story is a familiar one, especially for immigrant and first-generation Americans. In the struggle to survive, a chasm appears that pushes everyone away from each other and leaves people feeling unseen. Even if parents believe that pushing a child to excellence is a form of love, the effects can be abusive. The Big Bad is the perfect pupil of a genius scientist, but perfection leads to a broken mind and spirit. How can a breach of care and trust be mended?

“Everything Everywhere All at Once” calls us to be a mess, imperfect, and create space for love and silliness. Waymond’s love is ineffective in the face of the Big Bad because he has limits, but if Evelyn masters the Big Bad’s omnipotence and omniscience, she could be left feeling overwhelmed and hopeless. Evelyn’s challenge is finding the balance. The answer to Solomon’s human futility is accepting it and shifting the tone. “We can do whatever we want. Nothing matters.” The Daniels depict the third eye of enlightenment with Googly eyes. Daniel Kwan suggests, “The film gives us a language to pull out of suicide.”

Even though “Everything Everywhere All at Once” succeeds at fulfilling its admirable goal of healing people when society is at its lowest point to date, it felt a little long to get there. I appreciated the homages to Ari Aster’s “Hereditary” (2018), Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968), “The Matrix” (1999) and classic martial art films. The Daniels leverage Yeoh’s fame by using actual footage from her red-carpet appearance at the opening of “Crazy Rich Asians” (2018). The film never feels like a spoof movie but builds on its cinematic heritage. It takes narrative beats from films like “Mayhem” (2017) and “The Belko Experiment” (2016), which occur in bland, bleak office spaces, to set epic battle scenes in our current quotidian sites of tension and conflict. The contrast is always jarring. The Daniels never miss an opportunity to explore the practical absurdity of human existence. A less grotesque, more light-hearted Terry Gilliam undertone of humor is the cornerstone of this film such as giving an award shaped like a butt plug to an auditor. It is less a commentary on corruption than poking fun at human bodies doing absurd things to gain advantages against opponents.

It is a shame that “Everything Everywhere All at Once” was not released in time for the lunar new year, but it also works as the perfect film for the tax season. Its surreal genre bending will have something for everyone and have people wondering if they somehow chopped onions in the theater. Hopefully it will bring people together and reverse generational curses.