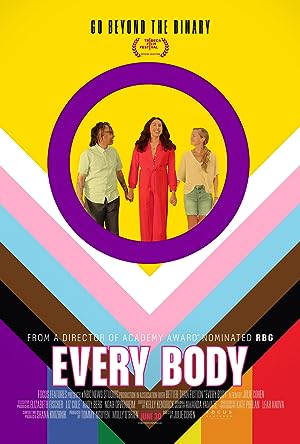

It is fitting that “Every Body” (2023) will be released at the close of Pride month. While many are familiar with LGBTQ, IA2 often appears at the end of some versions of the acronym. The “I” stands for intersex, a term for people born with sex characteristics that do not align with the male/female binary, which can include androgen insensitivity syndrome. For instance, a person may appear to have a vagina, but instead of a uterus, have internal testes. Director Julie Cohen interviews three intersex people: artist and Ph.D student Sean Saifa Wall, political consultant Alicia Roth Weigel and actor and screenwriter River Gallo. Their experiences serve as a jumping off point to explore the history of how the medical community treats intersex people and how the intersex community is pushing for reform in medical treatment, raising awareness and demanding acceptance from the public.

Cohen’s film has an upbeat and optimistic tone. The opening credits are a montage of over-the-top gender reveal parties. Cohen holds her own belated gender reveal backyard garden party for the trio by conducting the interviews outdoors. Every person is introduced with their pronouns, childhood photographs and a slice of life montage to show where they are now. There is a brief montage of popular culture images of “hermaphrodites,” and Cohen depicts intersex people as humans, not freaks. Positive representation matters, especially for intersex people who were tricked into being invisible. The trajectory of “Every Body” is towards success and change.

The middle of “Every Body” features the interviewees watching most of an episode of “Dateline” featuring David Reimer. John Money, a John Hopkins University alleged expert on sex and gender, is cast as the villain. In 1967, Money, treated Reimer, a twin assigned male at birth who was not born intersex. Reimer lost his penis during a circumcision accident at 8 months old. Money instructed Reimer’s parents to consent to Reimer having sex reassignment surgery and raise him as a girl without any information of the accident, but Reimer still identified as male despite his family and the medical professional community’s interventions. Money claimed that he succeeded in making Reimer believe that he was a girl, which laid the foundation for treatment of intersex children. Even though Milton Diamond, an academic sexologist, who was not featured in the documentary, and H. Keith Sigmundson, Reimer’s psychiatrist, got Reimer’s consent to tell his story then debunked Money’s socially and medically constructed and imposed gender identity recommendations, this treatment is still prescribed for intersex people. The film omits Reimer’s allegations that Money sexually abused Reimer and his twin brother.

I was not in a press-only screening. Whenever Money appeared on screen, the audience would hiss and boo at the screen. Reimer’s story elicited audible wincing from the viewers. It was like watching a horror movie except without the fun and laughter because the torture happened in real life. A couple of people could not handle it and walked out.

The Dateline excerpts illustrate the incessant early siege on intersex people, but it has the effect of completely marginalizing the documentary’s subjects. It is effective because society has viscerally programmed people to accept at face value the horror of a man being forced into becoming a woman. When Cohen uses Reimer as an example of the persecution that intersex people endure, she is transferring that innate sympathy for men to people with ambiguous gender and feminine features, but it does kill the momentum of the interviewees’ story. I’ve been thinking about if there was a better way to present the Dateline portion than sitting the trio on the couch then playing the episode.

Perhaps Cohen should have tried to intersperse Dateline clips as if Reimer was being interviewed at the same time as the trio would have worked, but the tone of this documentary and Dateline are so different it would have caused whiplash. Dateline is closer to true crime television genre, and Cohen’s documentary is a human-interest story with activist ambitions. Instead Wall, Weigel and Gallo’s descriptions of their childhood are kept separated. Their accounts sound like a horrific medical and social torture experiment that would shock and appall Pedro Amodovar (“The Skin I Live In”). Kids are gaslit into believing their assigned gender is their only gender, denied the knowledge of their ambiguous gender, forced to endure painful procedures as if they were broken, and shamed into keeping their identity a secret with the threat of ostracization. Later they discover that all the authority figures in their life lied to them so they could fit an image. Weigel describes doctors instructing her as a child to constantly use a dilator (medical dildo) to insure that as an adult, she would be able to have penetrative sex. Doctors cared more about the sexual satisfaction of Weigel’s future lovers than Weigel’s physical and psychological well-being as a child. These treatments sound like sexual child abuse.

The final act of “Every Body” depicts how the interviewees responded to the revelation of their intersex gender and eventually came out. Wall’s Berlin-featured photographic series is a triumphant rebuttal to the voyeuristic, dehumanizing medical photographs of naked underage patients in which he appears “butt naked for the art and the movement.” Weigel has a quick wit and has the best one liners. Gallo may have the most conventional trajectory from awkward theater kid to glamorous actor. There is also a snapshot of how the intersex movement is becoming politically active to stop the abuse.

Cohen usually collaborates with others as she did in “RBG” (2018) and “My Name Is Pauli Murray” (2021). I’m a fan of Cohen’s work because her subject selection shows that she has a good heart and finds amazing human stories to put on the screen, but the lack of collaboration may have weakened the overall pacing of the story. To be fair, her prior movies were biographies of a single person whereas this film is more ambitious and features three people while informing viewers about the history of intersex people.

The closing credits are jubilant and adorable as Cohen and the production team frolic in front of the camera with their pronouns printed on screen. Cohen is deft at showing, not lecturing, how people should act. Maybe gender reveal parties should be delayed until a person is old enough to take charge of their medical decisions, have access to their records and find their voice.

“Every Body” comes at a disturbing time of open global trans genocide, which is rationalized by the (unscientific and ahem, un-Biblical) claim that gender is a binary and easily definable. Intersex people’s existence refutes that antiquated notion; however, the documentary details how the medical community does not respect the bodily autonomy of trans or intersex people. Doctors deny medical treatment to trans people who request it while forcing medical treatment without informed consent on intersex children who are too young to understand their situation. Medical practice privileges how others feel about a person over how the person feels about themselves.

While neither the documentary nor the interviewees explicitly claim that intersex people are experiencing genocide, they are. Genocide is defined as an elevated, intentional, and systemic discrimination and destruction of a type of people. It is not just killing, but preventing the birth or existence of, causing physical and mental harm to, and imposing destructive living conditions on a group of people. “Every Body” is the kind of film that everyone should see so they can get educated, but because it is a preach to the choir film, the viewers who want to see it are probably the ones who are already inclined to side with intersex people.