Because I do not eschew all gender normative behavior, I am into Jane Austen-the books, the movies, the television miniseries, but because I see too many movies and am an adult, if I have to postpone seeing a movie in a theater, I will prioritize other movies and wait to see the Jane Austen film. The Jane Austen film will stay in theaters longer than any other film because of its widespread appeal to women and older audiences who will use the excuse of the film being a period piece and/or explain that they are Anglophiles as a respectable veneer for basically watching a romcom. Because I have seen so many of these films, there is no longer a sense of urgency to get to the theater. It can wait.

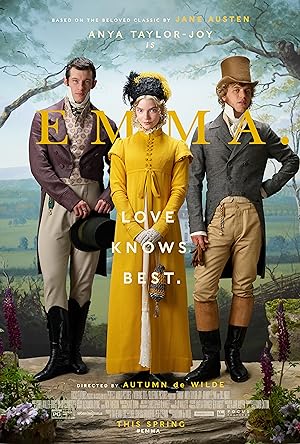

When I saw the preview for Emma., the latest iteration starring Anya Taylor-Joy, I knew that I would see it, but when and where were up for grabs. I initially waited until the second week because I knew that it would be moving to a theater closer to me, a local chain versus a national one. Then I waited until its third week because there were a lot of other good movies competing for my time, and after almost a lifetime of seeing British films, let’s give some love to other countries such as India. Then a global pandemic started, and I was not about to risk my life to see another Jane Austen film so I sadly put it in my queue and waited for it to become available for home viewing. When I eventually got the DVD, I waited to see it after the other DVDs that came with it. The cast looked amazing, there was a distinct, snappy tone, but it felt like a commitment, specifically a two-hour four-minute commitment.

It was at the beginning of the film that I realized it was not Emma, but Emma., which I thought symbolized the emotional turning point in the story when Emma’s name is sarcastically defined as perfection to end a cruel game, but no, I later found out that Autumn de Wilde, a first time feature film director, used it to signify that it is a period piece. Please tell me that she was joking. My explanation is better, but this title is a microcosm of the film’s flaws. It is style over substance, which is not necessarily a mortal blow for a film that is essentially a classic rom com, but is still a problem that puts unnecessary drag on a film that should be absorbing. I should not ever want to leave this world, but only a little past the midpoint, I was checked out and eager for the proceedings to end.

Emma. reflects its titular character’s psychological makeup, which may be intentional. It is eager to be admired for its good traits and intentions, but by bringing attention to them, undermines its goals. There are flashes of cheeky postmodern moments of abruptness, literally and visually metaphorically to bring out the absurdities of each character and society. These scenes work when they make sense in context such as when the titular character opens a carriage window with one finger and the window creaks to reflect her disdain, lack of interest and reluctant sense of obligation to interact with a person seeking her attention. The camera work, acting and sound show more about Emma than any phrase could. She is a god from Mount Olympus deigning to shower the slightest amount of attention on her subject. Other moments are painfully more for the visual punchline than to depict a deeper insight into the character. When the film introduces Bill Nighy, who plays Emma’s father, he leaps off a stair case and onto the stage as it were while rushing forward allegedly having a conversation with his daughter who is rooms behind. It is hilarious and a very appropriate way to introduce Nighy the actor, but perhaps too vigorous for the hypochondriac that he is playing. De Wilde is not the only director who commits this visual sin, but I detest when scenes are directed to be cool and punchy, but actually do not logically work. If a character could not hear another character in another room to respond, then do not have that character respond as soon as she appears as if she could. There are lots of little moments such as that including Mr. Knightley talking to Emma’s back while standing behind the couch that she is sitting on after he comes in. It looks great, infuses a certain amount of action and snap into the dialogue, but subconsciously bothers like the pea under the mattress.

Emma. shamelessly tries to have a couple of Darcy swimming in the lake scenes. If you are not familiar with the BBC miniseries, Pride and Prejudice, it is the precise moment when most people attracted to men fell for Colin Firth after he went swimming in a white shirt and decided to unwittingly enter a wet t-shirt contest (not me, I fell when he got older and started wearing glasses) for Jane. This film ups the antes and gives us interior shots of butts, thighs and legs. Guess which two are going to fall for each other? It worked on an emotional level to show their similarities and to subconsciously have us associate the only two semi-nude characters with each other in flagrante though in those scenes they are apart and behind closed doors, but it is also so not Austen.

Emma. is a highly stylized movie that deliberately takes place during the course of a year, yet the scenery changes very little to reflect the changing seasons, which it deliberately uses to unnecessarily divide the action into chapters. The film works when it acts as a character study of its protagonist, not as a commentary on society. Taylor-Joy is a great actor whom I enjoyed in Thoroughbreds and Split. She manages to deftly show the war between her role’s better angel and her wicked devil alternating between enjoying using her influence and power to arrange things a certain way and showing genuine warmth to people of lesser stations instead of someone who wants to surround herself with lesser people in order to elevate herself. De Wilde and Taylor-Joy manage to create a character that cares little for class divisions and prejudices while enjoying the privileges of both. Her role as the stabilizing, sober force in her family and immediate circle make her seem less delusional to think that she should play an active role in others’ lives. She comes off as a neglected child who responds by becoming the caretaker instead of being bitter, but the negative effect is seeking to be the center of attention elsewhere.

Emma. has a single scene that crackles in the way that Greta Gerwig’s Little Women did when it focused on Amy and the economic plight of women in that period. It occurs during an early fiery exchange between Emma and Mr. Knightley as they discuss the marriage prospects of her friend, Harriet Smith, whom Mia Goth is unrecognizable while playing. Emma clearly feels that women get a raw deal-criticized when they only possess the qualities that men find attractive. It is implied that Emma’s lack of interest in matrimony is because she wants to be her own master and possess whatever qualities she deems fit. She wants to take action, not be acted upon, which imbued the later scene with Mr. Elton with more menace than I had heretofore felt.

Emma. is an indulgent film that could potentially lose the interest of the most devoted Austen lover, but it is not devoid of making a ripple among film adaptations of the popular novelist’s books. It is an uneven film that with a little more grounding could have made as much of a splash as its director intended. With a little more organic direction and less ostentatious frills, it could have shone.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.