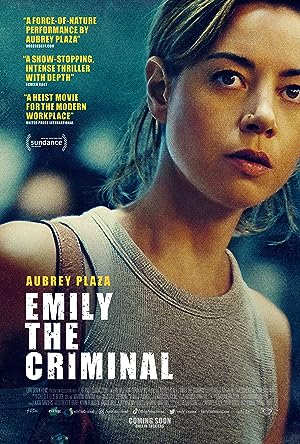

“Emily the Criminal” (2022) stars Aubrey Plaza as the titular character. With a criminal record and mounting debt, Emily is stuck in dead end jobs. When a coworker offers a one-time gig that pays $200 for one hour, she does not hesitate until she discovers that it is illegal. As she gets past her initial qualms, the money becomes too good to pass up despite the intensifying danger. Just when things start to look up, they may be getting worse.

I love Plaza, but I had zero interest in seeing “Emily the Criminal.” Other than her television roles in “Parks and Recreations” and “Legion,” her movies have not lived up to her talents even such critically acclaimed indies as “Safety Not Guaranteed” (2012) and “Ingrid Goes West” (2017). Also there is an elephant in the room that turned me off-the presumptions about the titular character based on her gender and appearance as white or at least white passing (I have no idea how Plaza identifies, but a quick Google search suggests that she is Puerto Rican with Caribbean indigenous and European roots). It plays on the audience’s assumption that white women are not expected to commit crimes whereas women from the global majority must battle the opposite presumption in the US. White women are human beings, and all human beings can commit crimes and are not inherently criminal or pure because of some physical characteristics.

When I read a movie review that compared “Emily the Criminal” to “God’s Country” (2022), the critically acclaimed movie finally got my attention. While I think that “God’s Country” is the superior film, Plaza finally got a chance to disappear into a three-dimensional character that bears no resemblance to April Ludgate. It was easy for me to let the story and its protagonist sweep me away because writer and director John Patton Ford keeps things simple in his feature debut. Plaza and Ford made Emily into a real believable person that we could know and like because of her flaws.

Emily is a person willing to lie, work hard and speak truth to power despite being powerless because she knows that she has already lost the stacked game so at least she wins a pyrrhic victory by calling people with power out on their bullshit—they too are lying, tricking her, taking advantage of her or being unreasonable, but only she is held to a higher standard. She is worthy of taking center stage because while she belongs to the lowest economic class, the gig economy with no rights, she refuses to obey the rules of her caste, obedience, politeness and never showing unpleasant emotions, and is trying to escape. She is an every woman underdog, but is elevated by refusing to let people kick her without consequences. She may not win, but she fights back. I liked that the film was rooted in real economic stakes and reflected the reality that having a criminal background shrinks any slim possibility of upward mobility to almost nothing. So it feels plausible that if she is failing to find legal opportunities for stability. Employers do not see her as a brain, just a body to move things. Being tempted to take risks that could expand her criminal record makes sense though it does widen the ouroboros of her job prospects.

“Emily the Criminal” establishes her world, her hopes and dreams—motivation, a call to adventure then the obstacles to her hopes and dreams. It rinses and repeats with all its supporting characters, who are just as interesting and enticing as the protagonist. I thought it was an interesting choice to cast Megalyn Echikunwoke from “The 4400” as Emily’s best friend, Liz, living the life that Emily wants. It taps into the potential viewer’s cynical anger that resulted in the election of Presidon’t, which is thankfully missing with Emily, who never resents her friend. After one of Emily’s verbally explosive moments jeopardizes Liz, Liz still wants to maintain the friendship despite her cluelessness and obliviousness about how desperate her friend is. There is an unspoken resentment when black people have something as if it takes away from a more deserving white person. While the film is not explicitly saying that, regardless of whether it is intended, it evokes that dynamic of “economic anxiety” that the media likes to use for Presidon’t supporters. Liz is part of the haves and is aspirational for Emily.

Another bit of dream casting is Theo Rossi as Youcef, Emily’s handler and mentor in the criminal life. Rossi may be best known for playing Shades in “Luke Cage,” another smooth criminal with a fondness for explosive and powerful women. His calm demeanor, empathy and solicitousness makes him a figure that is easy for the viewers and Emily to trust. Unlike most of the people in Emily’s life, he cares about her feelings and well-being, and is not indifferent, dismissive or deliberately ignoring her as if she is nothing and does not matter. They find common ground as he shares his hopes and dreams, i.e. his motive for living this life. The lines begin to blur between their worlds, which allows Emily to show sides of herself that would not have been possible without the comfort of money. “I just want to be free and experience things.” Her growing connection to him also reveals a part of her past life that she barely talks about but had a huge influence on her identity—her grandmother. She gets to be a whole person around him and not seem like an idiot for trusting another criminal.

“Emily the Criminal” is not perfect though I am thrilled that it embraced a hard anti-heroine who forces herself to become more comfortable with being violent. Usually films pull punches and try to soften a violent woman. I used to watch “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and thought it was the most feminist thing ever. It took awhile, but people (not I) pointed out how she was objectified, and I could not miss that in this movie. The camera is practically salivating over Emily by lingering on her chest when she decides to not wear a bra or shows her ass when she decides to have public sex. Emily is the protagonist, not the seductress. The camera should be ogling Youcef if the film’s sympathies are with her. By the end of “Emily the Criminal,” I wondered if Ford was inspired to write this film by following a writing prompt to make a femme fatale sympathetic to show that she was not trying to destroy the man that falls for her charms, but genuinely cared about him.

More kudos to casting John Billingsley, whose voice I recognized at the beginning of “Emily the Criminal.” Also casting Gina Gershon as the final boss was a brilliant move, and I wanted the scene to even be longer after all that build up. While Ford pulled punches at the end and perhaps fell a little in love with his protagonist, they are forgivable sins for such a dynamic, character driven movie. I am looking forward to his next film.