This review was originally published on Roarfeminist.org

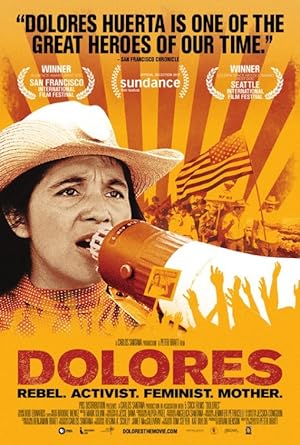

Who are the founding mothers of the United States? What does a revolutionary woman look like? Maybe she looks like your abuelita, but she can still cause men to clutch their pearls and faint in horror at her audacity to tell the truth. Whereas historical figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. were assassinated, allies and enemies are literally trying to erase Dolores Huerta, but she is still alive, fighting and the focus of a ninety-five minute documentary called Dolores.

To some, the idea of paying to see a documentary for entertainment can feel like eating uncooked, unseasoned vegetables for dessert, but Dolores feels like a virtual mentorship on how to live well during this era. At a time when unions, Mexicans and women are explicitly being attacked by our government, a documentary has never felt more urgently germane since I Am Not Your Negro though it has a more conventional and ebullient structure. The film presents her life story in a chronological fashion, primarily focusing on her founding of the United Farm Workers of America and the Delano grape strike, but also explores how her activism organically intersected with other issues such as feminism, cultural pride, environmental activism, immigration. It uses archival footage and interviews with the titular shero, her family, prominent activists and academics.

Dolores poses a central question in two different ways. Would you assimilate and live a comfortable life or be yourself and live a meaningful life? Andrew Hacker defines a comfortable life in Two Nations: Black and White, Separate, Hostile, Unequal by introducing the concept of different sets of immigrants eventually being adopted into whiteness after initially receiving nothing but prejudice. Making the choice to align oneself with the majority during the 1950s and 1960s when it was considerably more difficult, and there were few to no media representations of what a different path may seems more like a reward and less like a betrayal. Now 33% of self-identifying Latino men and 26% of self-identifying Latino women, not including the Latino men and women who only identify as white and no longer acknowledge any association with being Latino, voted for someone who has proudly disrespected them. Huerta then and Dolores now explicitly reject and instead recognize the similarity between the de jure enslavement and civil rights struggle of African Americans and the de facto enslavement and economic justice struggle of Chicanos, particularly undocumented immigrants.

What would you do if someone gave you money? Huerta does what Bernie only preached (relax, I voted for him in the primary)-live a democratically socialist life with the people that she fights alongside, the farm workers, and constantly redistributes whatever money she is given to them. She still put her aged body on the frontlines and does not have to go as far back as marching with King to show her near-death battle scars at the end of a policeman’s baton. These are not easy choices. It is quintessentially human and relatable to keep the money and stay with the majority, but these decisions are noble and heroic ones; however Huerta never gets placed in the pantheon of American heroes like her contemporary and fellow freedom fighter, Cesar Chavez.

Dolores is not simply a soft-focused, vanity documentary, but uses Huerta’s life to examine the specific difficulties faced by women in the vanguard of any movement. Women don’t get to simply be people like men so they do not get to have their flaws or shortcomings later erased and then promoted to perfection (RIP Mandela). At the height of her activism, without explicitly calling her one, she is slut shamed for divorcing twice, having children outside of marriage, not being a stay at home mom to her eleven children—being Catholic and initially pro life did not save her. If the women in Hollywood are annoyed at getting asked questions about their diet and clothes, Huerta truly embodied nonviolence for not flipping tables or seeming slightly angry at being asked if she wanted a spa day while seated next to Chavez. Her children, who are now adults, do give us a glimpse of her style choices: no nose jobs-be proud of your ancestral, Chicano nose! Brown is beautiful. Instead of receiving respect, the Arizona politicians who successfully fight against ethnic studies incorrectly characterize her as Chavez’s sidepiece (she had a relationship with his brother after forming the union), and the men in the union that she founded pushed her out. Even a woman in power who creates an organization is considered a temporary placeholder for a man to take over—one and done. It is a matter of pride, not embarrassment, for a recently fired FOX figure accused of sexual harassment to admit that he didn’t know her.

Dolores’ most salient point is the hate tree. The hate tree has numerous branches: sexism, racism, homophobia (which is not explicitly discussed, but there is footage of her marching in pride parades), xenophobia. They are interrelated so to effectively fight against hate, everyone fighting against one branch from the hate tree must unite with groups fighting against different branches. Even though Huerta started her fight against the unholy union between business and national and state government, she ultimately realized that her battle against prejudice was one that she would have to fight at home with friends and family on multiple fronts. Women may do the work, but they don’t get the credit. Brown people may belong to a union, but whether it is because of their Mexican heritage, linguistic differences or brown skin, other union members such as the Teamsters felt more allegiance with agribusiness than the UFW.

The hate tree denies the label of American hero to Huerta because it also denies someone, regardless of sex, descended from a man who fought on the Union side the label of American. Please note that she does not deny being an American, upholds the nation’s ideals by admonishing people to live according them, but acknowledges, “I found that no matter what I did, I could never be an American. Never.” Doesn’t that sound familiar? When a first generation, draft-dodging, Gold Star family mocking American feels empowered to chide other Americans who have been here for generations, perhaps since the beginning, for the way that they embody our country’s ideals and admonish our nation to do better, where is the lie? American is sadly not defined by many as one’s place of birth, naturalization or allegiance to ideals, but equated to the 1950s invitation to erasure, which Huerta rejected. Put up or shut up. Being different is the crime, not explicit violation of the law.

Dolores and Huerta leaves one lesson to the audience: be a pipe, not a bank. Power should flow through you instead of being hoarded. As a community activist, Huerta showed other brown people, Spanish speakers and women that they too had a voice and deserved a seat at the table. Use your skills and resources to empower others instead of hoarding glory and money, but don’t shirk away from getting credit for your ideas. Huerta is equally unbothered in the face of criticism and praise from would be and actual Presidents. She never changes. The audience does.