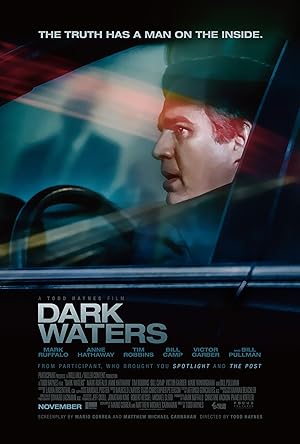

Dark Waters is credited as an adaptation of New York Times Magazine’s “The Lawyer Who Became DuPont’s Worst Nightmare,” written by Nathaniel Rich, but according to Wikipedia, parts of the story were also adapted from HuffPost’s “Welcome to Beautiful Parkersburg, West Virginia,” by Mariah Blake and The Intercept’s “Bad Chemistry” by Sharon Lerner. The movie’s protagonist, Robert Bilott, a partner at a well-established law firm, played by Mark Ruffalo, everyone’s favorite Hulk and progressive, also wrote a memoir, Exposure. So if you don’t have time to read all this material, this movie is for you, but once you do see the movie, you will probably want to read all of it anyway. As soon as I came home, I added The Devil We Know, a documentary about DuPont allegedly exposing humanity to deadly chemicals, to my Netflix queue.

Dark Waters belongs in the same genre of movies as A Civil Action and Erin Brockovich, who is not a lawyer, legal dramas without any sensational moments of triumph, but long slogs of hard work that barely ruffled the feathers of the big bad while exposing the vulnerability of the lawyer and his client. As a lawyer, I usually despise movies about the legal world, but these films are the blessed exception to the rule because they accurately depict what practicing law is like. What distinguishes this film from the others is how Dark Waters is as much a movie about class (and race) as it is a David and Goliath movie about a person facing corporate malfeasance. It is also a horror movie like It Chapter One (never Chapter Two) in which human sacrifice in exchange for prosperity becomes a part of the deal either knowingly or implicitly.

Dark Waters uses coded quotidian moments to depict vulnerability because it is more like The Hound versus The Mountain story rather than David and Goliath because it pits big money against bigger money. The movie is part biography of Bilott and part chronicle of the leading plaintiffs’ story of how they try to get justice against a big corporation, which also carries an inherent problem in the narrative as the latter story eventually overtakes the first, which could feel like a lack of focus for viewers who relate to Bilott more than the changing plaintiffs (one viewer left the theater and never returned) or are less invested in the actual outcome of the case. There are two fears in the movie: the fear of sliding back down the class ladder (class mobility goes both ways) and the fear of literal murder by poisoning with zero consequences.

I have pointed out in prior reviews, specifically Concussion, that films, especially ones with laudable liberal agendas, will use a black character to explicitly say the unpopular thing that the majority may be thinking. So the film expunges any explicit guilt from the complicit majority so audiences can assuage themselves that if they knew better, they would not act like that wrong black character, which creates the hopefully unintended racist effect of further othering black characters when in reality, if only black people were allied on the wrong side of history, bad acts could never continue because the majority would simply move in a different direction, and life would be different. We would live in a utopia, which has not happened.

In Dark Waters, the black character, James Ross, a foil for Bilott, a new partner and the only black one in the scene, is given the job of vociferously defending the law firm’s long standing tradition and sides with DuPont in hopes that the corporation becomes a client in the future. Tim Robbins, who plays Tom Terp, the managing partner, stops Ross’ attacks on Bilott’s proposal to change the firm’s allegiance, “I’m running this meeting.” At this point, the film felt like a documentary. Yes, the firm when confronted with the state of its soul and challenged to change its actions is understandably reluctant to side with murderers no matter how lucrative, but it is also about whiteness deciding who should have power, who gets to have a voice, and even when money and the facts of the firm’s history are at stake, a black voice that sides with the establishment, money and historical precedence must always be quieted so the real voice and image of authority can be retained. The real stakes are about the image of power, which never changes throughout the film. In this case, it is the tallest, white male voice that happens to fall on the right side of history, but only in word, not in spirit.

Dark Waters shows how Terp and others in power gradually push Bilott to the margins of a class that he fought hard to achieve because he chose to hear the call of his past and acknowledge his heritage. Other partners hint at their humble beginnings, but never openly acknowledge them. Bilott, though initially just as horrified when presented with the rough, brusque ghosts of his past, is willing to try and remember. Like It, there is an amnesia that comes with survival and ascendency, but his refusal to forget puts him back on the chopping block. Initially he gets to stay in the boys club, get served by black men in formal attire, hobknob with men in power, including the DuPont contact, played by the magnificent Victor Garber, but by refusing to deny his heritage and abide by their rules of polite society—what to wear, when to talk business—and using common sense strategies offered by women, specifically his secretary, he forever signals to the class that he wants to belong in that he is not one of them. His exile comes soon thereafter. The film shows that part of belonging to that class is not socializing with the help, i.e. women associates, or wives longer than you have to, which he does. The mobility ladder only goes one way, and no one wants to be Lot’s wife. Terp’s abrupt end to his polite exchange with Bilott’s wife shows that attention is only warranted as long as someone more important is not in the room. To the outside world, Bilott is still a partner, but everyone who actually belongs to that world knows that he is an outlier. He moves from being served by black men to entertaining experts in restaurants without an expense account to eating with his family at Arby’s with the hoi polloi. He did not get fired from whiteness, but he definitely got demoted and is only just above those that he chooses to represent, which makes him vulnerable to condemnation from all sides. He no longer belongs in the same bubble of protection and security that he had at the beginning of the film when security would have happily dragged people who bothered him away from his presence. He is a traitor to both sides by trying to do the right thing.

Dark Waters could have used some tightening up. For instance, the paranoid points did not quite work. Was there a credible, real world threat of violence or is a possible side effect of being poisoned that you thought that someone is trying to physically hurt you in addition to poisoning you? The thriller moments seemed extraneous considering how innately horrifying the entire story is and is probably/hopefully fictional. The introduction of Bill Pullman’s character threw me off because it was not clear if he was going to screw up the case so while Harry Dietzler may have played a pivotal role in the real world, the movie failed to convey it and probably should have omitted his character.

While it is not as riveting as Parasite or Motherless Brooklyn, Dark Waters shares a similar visual and narrative bond with these films. It had a very cold, blue palette, but Dark Waters began similarly to Parasite during the opening with the credit and image placement showing how the framing obscures the complete picture of the story. Stay for the end credits to get a glimpse of the real life people who are depicted in this film.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.