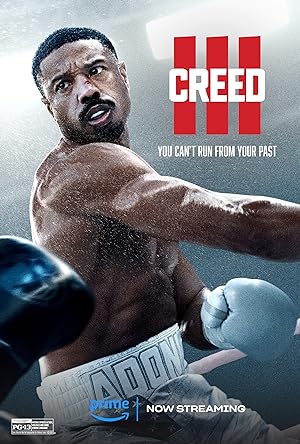

“Creed III” (2003) is the third film in the “Creed” franchise. If there is no Rocky (Sylvester Stallone), is it still a part of the franchise? If the answer is yes, then it is the ninth in the “Rocky” franchise. Adonis “Donnie” Creed (Michael B. Jordan) retires a champion in and outside the ring, but when “Diamond” Damian “Dame” Anderson (Jonathan Majors), a childhood friend, resurfaces, Donnie’s old memories begin to haunt him and threaten to destroy everything that he loves. By facing Damian, Donnie can stop running away from his past and enjoy the present.

After “Creed II” (2018), I began to question whether every film would be closely tied to the “Rocky” films, or would Creed ever reach a point where he is a seasoned professional with his own story without needing Rocky to jump in and save the day with his inspirational words. It worked in “Creed” (2015) to lay the foundation and resurrect the story, but in “Creed II,” Donnie was the least interesting character in his own film. I also hate when a franchise’s first film establishes a professional camaraderie then instead of allowing audiences to enjoy it, breaks them up so they can reconcile at the end.

Y’all Jordan did the thing! “Creed III” is the best one in the franchise. It is not about Rocky anymore or even about Apollo. Donnie finally takes center stage, and the story tackles a hard concept. In “Creed,” Donnie wants to be a boxer and sacrifices a lucrative, safer white-collar career to achieve his dreams. In “Creed II,” the next generation is finishing their fathers’ fight. In this sequel, Donnie gives up his dream at the top of his game and becomes a mix of business and boxing, but audiences are not interested in watching someone be happy. Conflict gives a story momentum, but Jordan also finds a way to make the first act into a portrait of success that never bores but is sleek and gets us invested in Donnie maintaining his place on the mountain. He is the American dream achieved.

“Creed III” is set in Los Angeles and takes no detours to Philly. Jordan’s directorial debut is a love letter to this city. His home, which feels torn from the pages of Architectural Digest, is warm tones, mood lighting, a wall of glass framing the distant city below. Donnie the father plays with his little girl, Amara (Mila Davis-Kent), and nurtures her pugilist ambitions. Donnie the husband encourages his wife, singer turned producer Bianca (Tessa Thompson), in the studio and plays the supportive husband at her label party. Donnie the son wants to take care of his adoptive mother, Mary-Anne (Phylicia Rashad). As a manager and founder of Adonis Creed Athletics, he is the head of a gym and fighting community that fosters respect instead of stoking rivalry with some nice cameos from earlier former antagonists turned collegial colleagues.

In a nice touch, the gym is no longer homogenous, but features women at the sidelines, including coach Ann “Mitt Queen” Najjar and depicts a Mexican boxer, Felix Chavez (real life boxer Jose Benavidez), as Donnie’s successor. Like “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever” (2022), Jordan creates space to praise Mesoamerican culture in the match’s pageantry. It also echoes “Black Panther” (2018) in the way that Donnie associates with women, basks in his kingdom, rejects warning signs, and aims for healing when he reconnects with Damian.

If you have ever seen a movie, you will predict Damian’s scheming as the antagonist, but Jordan and Majors bring out nuance in the conflict as hurt kids trying to find a way to heal, but hurt instead. During the early scenes, Bianca and Donnie gently offer hospitality to Damian. Damian finds common ground with Bianca’s loss of hearing, the loss of a dream, and is baffled, even disgusted, why Donnie would ever give up his dreams. Jordan juxtaposes the class differences through dress, home life and mode of transportation. Everyone knows that bus equals poverty, especially in LA. Majors carries around this thin notebook, and we never find out what is in it, but it is clearly precious to him. He veers from bashful with a nervous laugh to a sneer or an open sign of vulnerability. It is a nice performance that does not turn into a cartoonish villain. After seeing “Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania” (2023), it will surprise no one that Majors is convincing as a gifted, raw boxer. When Damian moves up in the world, Jordan just shows the improvement in his environment and the appearance of an entourage. Because Donnie is the protagonist, we do not get to see more of his meteoric rise or how he badmouths Donnie, but the allusions are sufficient.

Humanity is complex. Damian feels abandoned and betrayed, and Donnie feels guilt, but they also know that these stories which they have told themselves loses sight of a lot of complicating factors that lay outside of their control as children. Damian still feels as if he should be superior to Donnie, and Donnie does not disagree. Donnie is conflicted with what is best for himself and paying respect to a brother. Damian’s accusations echo Donnie’s self-condemnation. So naturally they will beat the shit out of each other to get to a resolution because “Creed III” is still a boxing movie, and some tropes need to be played out. To heal the inner child, audiences are going to need to watch two grown men fight.

“Creed III” is about Donnie having to fight himself by fighting Damian. Through one character’s death, he and Bianca turn to each other to be each other’s confidants, feel emotion and face the past. Even without Damian, Donnie’s connection to his daughter awakens his past because she is the same age that he was when he began to suffer as a child. His encouragement of her dreams has a different significance for him, a way to protect her, than it does for her, a way to emulate him, but they still find common ground in the ring. He was on the path to healing his trauma even if Damian never appeared. His goal is to address the past so he can enjoy the present.

Donnie must train once more, and it is a great sequence. Instead of running up the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s steps, Donnie is running up a famous Hollywood hillside. Prior to the denouement, Jordan’s fight scenes clearly convey the action, and Fred Astaire would be proud. We see where the blow lands and how the blow affects the one hit. In Donnie’s first fight, Jordan uses slow mo to depict Donnie’s thought process and strategy. The final fight is more expressionistic, abstract and a bit choppier in terms of understanding who was winning. It was a switch to chaos cinema and his only first directing indulgence to prioritize conveying the characters’ emotions over their place in fight, but I wish that Jordan struck a balance. It was probably difficult to suspend disbelief that Donnie could beat Damian.

So if people do not like “Creed III,” it will be because there is no Rocky. People of color dominate this film. Because Donnie is more mainstream, he gets to represent the US, wears white as the good guy, and Damian wears black with little ostentation except some red, black, green and yellow lettering while hailing from Crenshaw. One is the approved version of palatable, respectable blackness, and the other is less so. Donnie’s patriotic robe also feels distressed, as if the reds were bleeding and smeared with other visual coloring that seem to echo Damian’s lettering, but not precisely.

I do not recall “Creed III” having any profanity. There is no nudity. Even though there is violence and blood, it is tame. Even though the previews show a jail visit, those scenes were cut from the final cut. There are some nice television segments seamlessly done. I loved that American Sign Language and Spanish appeared in the film with subtitles. I saw the movie in a screening and would happily pay to see it again.