If Experimenter and portions of Werner Herzog’s Into the Abyss had a film baby, it would be Clemency. Alfre Woodward stars as Warden Bernadine Williams who oversees the incarceration of around one thousand men, not including her staff, and some executions, which has begun to take a psychological toll on everyone, but the movie predominantly focuses on her. Unlike Just Mercy, it is not directly taken from a true story, but apparently it was inspired by Troy Davis’ execution. If Just Mercy is the happy side of the coin, Clemency is the flipside that is probably more common.

If your instinctual reaction to Clemency’s premise is outrage, I understand. The idea of privileging the feelings of a guard could sound sociopathic as if the guard is the real victim. We know that using the excuse of following orders to its extreme logic leads to violating Godwin’s law, but Chinonye Chukwu in her sophomore directorial debut (I never saw her first film) succeeds at showing everyone’s pain without losing sight of the real victim. Chukwu’s film reminds me of William Oldroyd’s debut film, Lady Macbeth, in the genius way that it navigates the ever-shifting rules of society depending on race, gender and class and becomes a brilliant case study on powerlessness with the veneer of authority.

Clemency shows and does not tell. It is a brilliant film because I felt as if I knew the protagonist’s life story without any character dumping prose instead of organic dialogue. Warden seems like a position of power, and Bernadine wanted the job to make a difference for men whom society usually victimize (contrast with the treatment of the prisoners and lawyers in Just Mercy), but it is an illusion. The unspoken trap of working within a system to make it better is that you also permit yourself to become briefly the personification, the body and face of the state, even when you disagree with the state’s collective actions. I have mentioned that being a lawyer and wearing a suit is the equivalent of being in power drag. The state does the reverse—it is made out of individuals and benefits from those individuals’ characteristics, appearances and demeanor, but other than as citizens outside their roles as instruments of the agentic state, the individuals’ influence on state action has limits, and when there is a conflict between the individual who has become a tool versus the agentic state, the agentic state will ultimately win and its largess and willingness to be an agent for good depends on those who make and interpret the rules. If those who interpret the rules are blind to experience, ignorant of reality or fail to adhere to the spirit and/or letter of the law, the instruments of the state become hostages whose spectrum of choices range from unquestioning obedience to outright insubordination, which would probably lead to termination and possible financial ruin.

At the bookends of the film, Clemency poses a problem of identity—who is the protagonist: the warden or Bernadine? It is a Bridge Over the River Kwai problem. People are hyperaware that men define themselves their jobs, but so do women. There is an innate sense of pride in doing a good job. For our protagonist, a black woman, to have such power over men, and for most people, her subordinates and prisoners, to respect her authority is no small achievement. Unfortunately in the collective subconscious of most people, black women are supposed to be motherly, nurturing, comforting or a lightning rod, an acceptable outlet to direct their rage. I found it riveting that other women, including one subordinate, did not respond to her authority, but to her as an individual even though she was interacting with them in her professional capacity. Men are not expected as part of the regular job duties to comfort, take sides or give in to anger. The mothers of victims try to take possession of her body, and Bernadine’s ability to successfully divert their efforts indicates her internal struggle, if she feels more like a warden or is experiencing inner turmoil and wants to respond to them as a human being. She cannot win-either she would be unprofessional for responding as a human being or not a human being by sticking to the rules. For most of the movie, she does not justify herself or show her true emotions, but the cracks are there if you are paying attention. She has the power to execute, but not to declare someone innocent or guilty. Everyone has been transformed into a murderer. Their jobs have become theater, and they are real people, not actors. You can tell that the protagonist feels the futility and absurdity of going through the motions, and she recognizes that no one will be grateful, nor should they be, for her decency in the broader context, which outweighs her individual efforts. She accepts the outrage and guilt because staying makes her complicit.

The prisoners are not the only ones dealing with their mortality. Clemency may be as close as an American film can get to dealing with mortality. There is literal mortality, but also metaphorical mortality of hopes, dreams and goals. Most of the characters contemplate retirement, promotions as a way of leaving the job or being taken out of a rotation because the weight of the job, regardless of their willingness to stick it out, is destroying them, or they are no longer capable of carrying out their duties. There is one scene with Crisis on Infinite Earths’ LaMonica Garrett in which one can easily imagine, in a different context with a different warden, there would be less compassion and brutal retribution. Each character is facing failures at the end of their lives. Even though the film talks about God and love, it feels more like Sartre’s hell. “I am Anthony Woods.” No one can be someone else. There is an aloneness that never feels breached even with human contact.

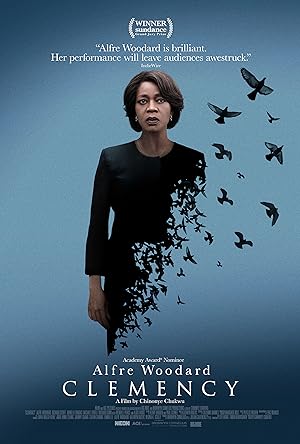

Alfre Woodward is freaking amazing in Clemency, a film filled with outstanding acting performances. Woodward is able to project inner turmoil on her face while reining it in with her professional, matronly physicality. If there is only one reason to watch Luke Cage, it is to watch her performance. Woodward is just soaked in so much truth, power and vulnerability in each of her performances that I do not understand how anyone can be unaware of what an acting powerhouse she is. I am unfamiliar with Aldis Hodge’s work other than Brian Banks, which is dreadful, but he honestly gave the best male performance of the year. I do not care who gets nominated or wins an Oscar or a Golden Globe. Hodge wordlessly destroys and lights up the camera depending on the moment. I really hope that he gets more opportunities to show his range because it would be such a waste for him not to use his gifts to their full potential just because he is a black man, and society believes that only one at a time can get lifted up. Hodge is a thespian and should snatch all of Tobey Maguire’s accolades, money and career. I also do not know Danielle Brooks. Brooks only appears in one scene, and she just encapsulates in her performance the overall tragedy of the film in a monologue that if life was fair, every actor in the world would have recite at auditions to prove whether or not he or she could get the part, and trust me, most actors would not pass. It was so understated, nuanced and strong that I do not understand why she and Florence Pugh are not in all the movies. Life is not fair.

Clemency is an amazing movie, but I know that my fellow moviegoers were bored. “Nothing happens.” I beg to differ. It may not have flashy moments or the emotional beats that we expect to leave us feeling uplifted, but it shows the world in an unflinching way that can be viewed as a cautionary tale of a group of people trying to do the right thing, but still failing and feeling that loss. “I have chosen a life of barely existing.”

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.