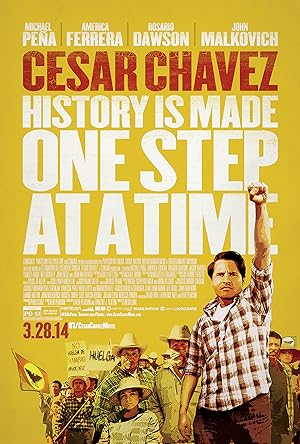

Diego Luna, some people’s favorite rebel from Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, directed, Cesar Chavez. Cesar Chavez, played by Michael Pena, depicts the titular character, his family and friends’ efforts to organize farm workers during the 1960s and 1970s. Cesar Chavez also reveals how the employers resisted this movement, and John Malkovich plays the employer leading the charge, who may or may not have been a more complex character than any real life counterpart.

When Cesar Chavez, the film, opened in 2014, it was not critically acclaimed and derided as a standard, forgettable biopic. For a moment, let’s say it is a standard biopic. Is there really such a glut of biopics for the heroes of the migrant worker movement? Do you find yourself saying, “Oh no, not ANOTHER film about Cesar Chavez!” I’m from the East Coast, and my mother was alive and living in the USA during the culmination of his fight. I can honestly say that even as a rabid movie lover, I have been largely ignorant of his historical role. Also complaints that the titular character is oversimplified seem unfair because Cesar Chavez is depicted as a great organizer, but a flawed family man.

I would also counter that while Cesar Chavez uses the biopic genre framework to structure the story, it deviates in three important ways. First, Cesar Chavez does not just show a mass of angry people against them, but really examines the marriage between all levels of government and business interests. Cesar Chavez then depicts the cultural weapons deployed to discredit and exploit workers: Communists, lazy, “go back to Mexico,” against “law and order,” “self defense,” which is countered by the titular character with references to being Catholic, Bill of Rights, public access to roads, freedom of speech. Cesar Chavez compares and contrasts the 53% white women as unofficial policemen who don’t feel safe when the workers gather together peacefully with the actual violent aggression faced by the female activists who get threatened with guns, arrested and sprayed with pesticides. Cesar Chavez really digs into the hypocrisy of the white imagination of fear and the actual violence deployed against people of color, including moving them across the border from Mexico to America as if it is authorized. Cesar Chavez paints an image of slavery that is reminiscent of the South, but takes place in California. What is extremely depressing is that these tactics have not changed.

Second, Cesar Chavez examines the intersectional issues faced among the activists, specifically between the titular character and his wife, Helen Chavez, played by America Ferrera. Even though women are in the fields and organizing behind the scenes, he frequently balks at the idea of his wife actually putting her body on the front lines and associating with other male activists. Cesar Chavez uses these moments in a humorous way, but reveals the drawbacks of Chavez’s impulse towards respectability politics.

Third, Cesar Chavez reveals the conflict within the movement between using violent and nonviolent tactics. Even Helen Chavez will pick up a pipe and come for you if you mess with her or her children. Cesar Chavez depicts the conflict as cultural, machismo versus Christian nonviolence. One is more instinctual and human than the other. Cesar Chavez basically forces the movement to become Catholic with a hunger strike and literally banishing people from the movement then breaks his fast with Communion.

I randomly decided to watch it within a week after Cesar Chavez Day, 3/31, with my mother, and I can’t think of a more appropriate film to watch at this dangerous time for workers, documented and undocumented immigrants, activists and Catholics in the vein of Dorothy Day, who provide a countercultural Christian reading to the one popularized by the white “evangelical” Protestant. Paired with I Am Not Your Negro, Cesar Chavez effectively compares and contrasts the ideals and realities of American life. Viewers will particularly empathize with Cesar Chavez’s lowest point in the film when the national political landscape changes.

Cesar Chavez is not a perfect movie. I actually did not like the overarching narrative framing device. The film is actually a letter written to Cesar Chavez’s oldest son, which I hate because the titular character has no way of knowing and recounting events that he did not witness.

Cesar Chavez’s cast is pretty outstanding, but Rosario Dawson and John Ortiz are underutilized. Unsurprisingly Malkovich steals the show, is the most interesting character and gets the best lines. He makes everyone equally uncomfortable in that silent, domineering tone. He claims the identity of an immigrant and the privilege of his skin wondering why his brown immigrant counterparts can’t get ahead while he puts roadblocks in their way.

I highly recommend Cesar Chavez for everyone. Cesar Chavez may be a fairly standard biopic, but it is a long overdue one.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.