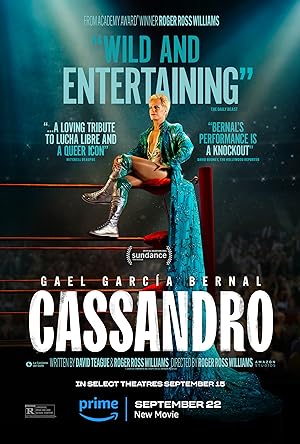

“Cassandro” (2023) is a fictionalized biopic based on Saúl Armendáriz’s transformation into his wrestling persona, Cassandro, the Liberace of Lucha Libre. Lucha Libre’s literally translates into free fight and refers to Mexican professional freestyle wrestling. On foot, Saúl (Gael Garcia Bernal) makes the trip from his hometown in El Paso, Texas to Ciudad Juárez, Mexico to wrestle as the losing, drab-masked runt. He admires exóticos, male luchadors/wrestlers who fight in drag. Exóticos are not always gay though they usually are required to lose and are the target of homophobic heckling. Saul finds the courage to become an exótico and decides to flip the script by winning with the support of his mother, Yocasta (Perla De La Rosa), and his trainer and friend Sabrina (Roberta Colindrez).

Expanding his thirteen minute documentary, The New Yorker Presents: The Man Without a Mask (2016), an adaptation of William Finnegan’s The New Yorker article, The Man Without a Mask (August 25, 2014), documentarian director and screenwriter Roger Ross Williams, an Emmy winner and the first Black director to win an Oscar, makes his feature directorial debut. Williams and Teague transition seamlessly into a drama with a rousing and inspiring story.

Williams, who is gay, set out to make a film that did not play into tragic gay tropes. “Cassandro” is a film about a man who stops bowing to convention. Once he believes that being himself is an option, instead of hiding his sexuality and his feminine side, he openly embraces both and abandons his feeble attempts of trying to fit into heteronormative roles. Like most sports movies, the training montage is key, but Williams merges the sequence with Saúl meditating over a makeover, which makes it feel riveting and fresh. Smaller than the other wrestlers, Saúl steps up his training, shaves his mustache, and begins to cultivate his new feminine persona, an opposite alter ego to his demure real-life self. His mother inspires his reinvention.

Once Saúl becomes Cassandro, his physicality evokes a Marvel superhero’s acrobatic antics and dramatic landings. Saúl’s showmanship fends off attacks by pantomiming one-sided stage flirtations. As his look evolves, his brocaded and colorful costumes embody the matador’s chaquetilla with a long train emerging like a cape from the back. His costume verges on couture—likely unaware of the connection with East Coast drag queens featured in “Paris Is Burning” (1990). The pageantry is more exciting than the highly choreographed, predetermined fights. Once Saúl stops hiding and is free to be himself, he becomes a champion.

Williams pursued Mexican actor Bernal as the lead for over a year, and his hard work paid off. Bernal plays Saúl with such infectious openness in the way that he drinks in his surroundings. Bernal starts by portraying Saúl as a tight and withdrawn character at the margins of the world that he loves. He is content to have a place at the table and glances wistfully at the colorful, unmasked exótico who command the stage. His ambition is never egotistical or off-putting. He looks up and confesses his dreams to a woman professional wrestler. His broad smiling enthusiasm makes him instantly appealing. Even when he wins, he is the underdog in a machismo-oriented world. Williams’ scenes are structured to protect Saúl. It is a delicate choice to wait until Saúl leaves the room before revealing his supporters’ backstabbing, homophobic ridicule and illustrates an understanding for those performers who remain closeted. There is an air of danger for pushing boundaries but have no fear. The real life Armendáriz is alive.

De La Rosa and Bernal’s chemistry as mother and son is the heart of “Cassandro.” Like best friends, they discuss their favorite soap operas, work from home, ride around on his motorcycle or in her car, and establish a routine that feels lived in and earnest. It is them against the world, and they are winning in their fierce admiration and gentle love for each other. Their bond echoes traditional testimonials of famous people trying to achieve money and fame so they can buy a house for their mother. So when she briefly rebukes Saúl for becoming a flamboyant fighter out of concern over his father’s reaction, it stings harder.

Williams’ poignant portrait of Yocasta’s pitfalls portends Saúl’s, including yearning over unattainable, married men who are ashamed of them. Williams and Teague get Freudian with seamless flashbacks to Saúl’s childhood with his dad, Eduardo (Ronald Gonzales-Trujillo), who introduced him to the sport. These flashbacks tie the whole story together in a neat psychological motivation bow without spoon-feeding the armchair psychoanalysis to the audience. Saúl comes to a crossroads of continuing to follow in his mother’s footsteps and cling to the idea of a life that he wants or believing that he deserves more even if it does not feel possible. He is forced to reevaluate the reason for becoming Cassandro if he is not doing it for his parents. There is a brief allusion to Saúl’s indigenous roots in a funeral ceremony then a feather from that ceremony becomes part of Saúl’s pre-wrestling routine, which was a nice subtle way to allude to the nuance of Mexican culture. Saúl can call on more than bullfights and Western emphasis on gender binary.

“Cassandro” loses some visual momentum as it reaches the culmination of his career, fighting the Son of Santo, a champion luchador with a wrestling legacy. Throughout the film, Saúl admires people on television, but during this fight, Williams switches the film quality to appear as if the viewers are watching him on television and later recreates a scene from Son of Santo’s talk show in which the champion interviews Cassandro. These scenes are supposed to be triumphant moments showing he finds acceptance from an icon in a gender normative profession. While Saúl’s personal life may not benefit from his professional achievements, Cassandro makes life easier for younger gay men and their families. Compared to the depth of feeling conveyed in earlier scenes, these snippets of fame feel frigid and fruitless, but carry enough hope and fulfillment that they do not derail an otherwise superb film; however it feel like a bittersweet end.

After watching “Cassandro,” if you want to know more about Armendáriz’s real life story, follow the links to the short and article to discover how Williams and cowriter David Teague’s story differs.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Was Sabrina a fictionalized character? Armendáriz’s parents were married! The community did not view his mother as the other woman. She was not mooning after an unattainable man. Also, Armendáriz had a serious drug problem, which was not only limited to recreational as depicted in “Cassandro” and was suicidal before his big match with the Son of Santo. It is interesting that to deviate from the tragic gay trope, Williams and Teague decided to make Armendáriz’s mother into an unwed single mother in a possibly predominantly Catholic community. So, they exchanged ridiculous societal stigmas. Is this respectability politics for gay men? Is it erasure to airbrush his addiction? Isn’t his ability to overcome it an integral part of an authentic narrative of usurping the tragic gay trope. Also, Armendáriz associated with other openly gay exoticos. He was just the first to win championships. Can someone make a reality show of Armendáriz’s life? Time to check out another documentary, “Cassandro, The Exotico!” (2018).