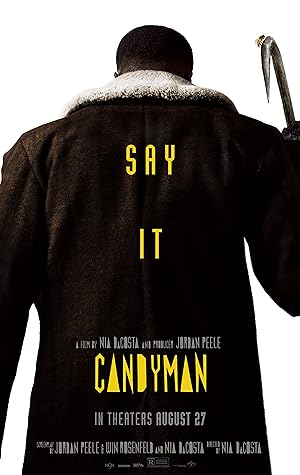

“Candyman” (2021) is a direct sequel to “Candyman” (1992) and focuses on emerging art elite power couple, Brianna (Teyonah Parris), an art gallery director, and her boyfriend, Anthony (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), an emerging artist who hasn’t started working on his next exhibit, a concept that provided fertile ground for psychological horror in “Hereditary” (2018). Unconscious of how each individual past trauma haunts them as they move into a loft on the haunted former site of the Cabrini Green project, their career profile skyrockets as a sudden rash of murders reminiscent of the urban legend dominate the news, the same legend which inspired Anthony’s latest work and pointed to Brianna’s eye for his talent. Nia DaCosta directs her sophomore feature film after the critically acclaimed “Little Woods” (2018) and cowrote the screen play with Get Out’s Jordan Peele and Win Rosenfeld.

“Candyman” is disappointing. It is a beautiful film featuring a talented cast that is bursting with provocative ideas that did not come together as a cohesive whole. DaCosta’s eye embraces the original and acts as a reprise. Her framing of the characters within the landscape is arresting and memorable. This Chicago is recognizable and beautiful to me filled with characters that I relate to and would socialize with if they existed in the real world. A running joke in the film is that most people of color absolutely refuse to say Candyman five times and act like they have seen horror movies except for Anthony.

Like Helen Lyle in the original, Anthony is at a career crossroads desperate to use Candyman to inject life in his career before he becomes what he fears the most, the stereotype of the unemployed black man whom a black woman must financially support. He and Brianna’s consciences are pricked at the idea that they may be the gentrifiers, the villains of the neighborhood. As the bodies pile up, they feel complicit as if blood sacrifices are required to obtain success. Initially Anthony seems eager to do it but becomes more passive in the denouement of the movie. While I normally would be eager for a black woman character to take center stage, it felt as if it robbed Anthony of agency. The central thesis seems to be that people in the art world use trauma to propel themselves but must be careful not to allow it to fully consume them. The meditation on art and trauma largely gets abandoned in the denouement.

A practical and social justice problem dominates “Candyman.” The practical problem is that Tony Todd, the original titular character, is too old to resume his role as Daniel Robitaille, and his take on the character is as iconic as Bela Lugosi’s Dracula and Boris Koloff’s Frankenstein’s monster. So Candyman is no longer purely a romantic, gravelly voiced Boogeyman in death trying to restore the life that lynchers took from him. Candyman becomes a placeholder for every black boy or man lynched through the ages, and this movie offers us numerous stories. “Say His Name,” the name of Anthony’s most famous artwork in his latest exhibit is a clear reference to Sandra Bland. It is an interesting idea in theory except it makes Candyman into a figure of vengeance, which I normally would find satisfying if the original Candyman’s favorite activity was not killing black women and children. Ummmm, huh? So, all the dots do not connect regarding how Candyman can plausibly transition from a spectre who terrorizes a black community to a champion. Also, it inadvertently erases an already underrepresented narrative of lynching of black woman by appropriating that phrase for lynching of black men, which is sadly well publicized and elicits more outrage.

When “Candyman” starts with shadow puppets, Daniel Robitaille’s Candyman’s original promise to Helen Lyle is fulfilled. She is the new Boogeyman granted eternal life. I did not want Helen Lyle to pop up in a mirror in this iteration, but I did not think that it was an accident that the first Candyman simultaneously wanted to ruin Helen’s life by isolating her from her friend, discrediting her career and reputation so she would accept his invitation to die, but perhaps also fulfilled her secret hidden desires as his reincarnated mate for a baby and a devoted lover. Initially the victims in “Candyman” are people that Anthony does not like, which is consistent with the earlier story. Anthony’s reputation improves with the murders, and he is never a suspect. The story starts to fall apart as it tries to explain what is happening to Anthony. If you saw the first movie, you should know who Anthony is.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Anthony is the baby that original Candyman fed with honey and blood from his finger, an evocative image that I had hoped DaCosta would somehow revisit in the sequel. The homicidal, nurturing father meeting his adult son dominated my hopes for this film. For all intents and purposes, Anthony would not become Candyman. He is the spiritual son of Candyman, whom Candyman was going to kill so he could live forever with his reincarnated family.

I loved the idea of a different young boy stuck in his trauma for feeling guilty about his role in the extrajudicial execution of the neighborhood mentally and physically disabled guy in the basement next to the laundry room. His inability to move on is embodied in his career choice—he owns and operates a laundromat. The idea that this boy would become an adult, William Burke (Colman Domingo), and solve it by destroying another black guy, Anthony, seemed like a lot, especially as Anthony passively lets Burke do so because the spirit of Candyman is consuming Anthony’s body thanks to a bee sting and/or razorblade cut from the candy. His skin is looking hive like or maybe burned.

I would have just preferred a transformation, willing or unwilling, without Burke’s help. White people lynching black people creates Candyman, not local black people. If the filmmakers are suggesting that you need a black person to intentionally create the conditions for a lynching to make the secret sauce for a vengeful Candyman, I needed that to be clearer, and considering that by the denouement, Brianna is a final girl whom we are rooting for, and she does not cosign Burke’s actions, it did not work for me. Side note: Burke was the name of Helen’s psychiatrist in the first movie. I love social justice themes in a film, but subtext became text and somehow made the supernatural horror less credible though the horror is grounded in reality. Usually injecting reality into film has the reverse effect.

I hated the decision to turn Anthony into a passive protagonist. Helen Lyle fought Candyman at every step. Anthony should have either gleefully embraced this sudden power or fought against it. Instead, he is no more than a possessed man. We never meet Anthony’s birth father, only his mother so there was a missed opportunity to treat Candyman as a father figure with a legacy that he either wanted to inherit or distinguish himself from. He could have still turned into a figure of vengeance as Helen did in the final scene of the original, but to reverse engineer and rehabilitate Candyman to make a point about extrajudicial killings did not feel as cathartic as the filmmakers probably intended.