Burning’s central character, Jong-su, likes to keep the television on in the background when he is alone even if he isn’t watching it. He is often alone. His TV is usually on a news channel, which discusses high unemployment among young adults. There is a brief clip featuring Presidon’t talking about his border insecurities. I don’t think these clips are random. This young man is near the DMZ, the military zone between North and South Korea. He is not conscious of it, but when people from more affluent, metropolitan areas visit him, they note the propaganda airing over the speakers. Everything has a cumulative effect even when we don’t notice it.

There is an anecdote, which may or may not be true, about Presidon’t’s physique. It reminds people of a hungry ghost, with his small mouth and distended belly that is always hungry and never satisfied. It is a picture of hell through dissatisfaction. Hunger is an important theme in Burning-small hunger for food, great hunger for meaning. Jong-su isn’t even aware that he is hungry until he is starving. As the movie unfolds, he is frequently seen reflexively shoving food in his mouth and drinking without seeming to enjoy it. He is more like a vampire however. In one mirrored scene, he has no reflection. Jong-su is also haunted by his father’s legacy and frequent calls with no one on the other end. His father also had potential, but look where he ended up. Will he become his father?

Jong-su is a child of an angry man, possibly a mad man, but he is laconic and anonymous; however he is less anonymous than he seems. He seems to be at his happiest and his most expressive when he is cleaning up animals’ excrement. If left to navigate the world and remain satisfied with his lot in life, he could live a quiet, peaceful life, but he is never left alone, and that contact makes him hungry. People notice him regularly throughout Burning though there is nothing of note to make him noticeable: a pretty girl shaking what her mama gave her for a going out of business sale, a neighbor lady, everyone in a courtroom, a wealthy young man, women working at a restaurant. The problem with being noticed is that then you have to interact with people, know how you measure up to your idea or absence of your idea of yourself once you are seen, your identity becomes solid, something that can be compared, be found lacking. It can become addictive to matter, to mean something. What would you do to keep being seen? Would you let yourself be exploited? How would you react if you thought that someone took it away from you? What if what people saw within you wasn’t real? Just because you want more doesn’t mean that you will get more from life. I’m seen therefore I am even if how I’m seen isn’t accurate.

The role of women in Burning and Jong-su’s life seems even more precarious than his. When he is soliciting signatures for a petition, a woman says no one is home even though she and a child are indeed at home. He accepts her answer and never considers her as someone who can sign the petition. He is looking for her husband, men, people that matter. The criticism of the men’s treatment of women is at the margins of the film’s actions, but ignored by the main character. Women are expected to provide entertainment while wistfully fantasizing how men in other countries treat women better. When he questions a friend’s coworker, she says there is “no country for women,” i.e. women are wrong no matter what they do. They seem to be more vulnerable to getting into debt. He may be unemployed, but he is at least welcomed at home or has a home. When you love a woman, you tell the closest competing man, but casually treat her like crap then wonder why she stopped talking to you. He sells the last woman in his life to the highest bidder. Women exist to be seen, but aren’t really seen. They are background noise always trying to get his attention. His face rarely registers that he notices them. The biggest surprise is an erotic makeup session in which a man finally gives his complete attention to a woman instead of seeming bored or unaffected.

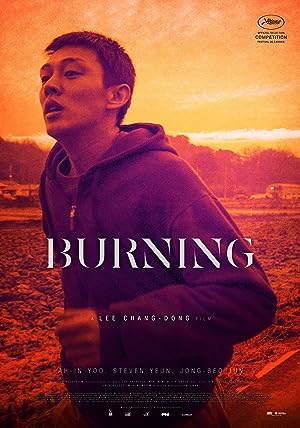

Who really exists? Burning addresses the quarter life crisis in a serious, existential way without being surreal or pretentious. At two hours twenty-eight minutes, it sounds excruciatingly long, but I have no idea what could have been cut out. I came for Steven Yeun, who is best known for playing Glenn on The Walking Dead. I’ve seen him shine in several movies outside of the successful TV series, but this role is the first time Yeun played a character like Ben, a vaguely sinister character in a supporting role that has to be played two ways for the story to work, and it does. Ben and Yong-su’s relationship feels ripped out of a Patricia Highsmith novel. I accidentally found out the ending when I was trying to find out whether or not any animals die in this film (they do not), but the whole movie still worked for me. Not all sociopaths are murderers although some are. Yeun brings a coldness and inscrutableness to his character that gives Yong-su’s suspicions credibility. They’re more interested in each other than the women that are present though the women act as a solid cover, a middleman, an excuse to connect. How do you connect if you are used to seeing relationships with men as competitive for scarce resources, inherently hostile or potentially criminal, then how do you respond to that attention?

Yong-su compares and contrasts himself to Ben’s inscrutable, smooth and socially acceptable way of navigating the world. Ben’s life could have been his if his father had made different choices. Even Americans whose only knowledge of South Korean culture is Psy’s Gangnam Style will pick up on the social and class chasm between the two. Is Ben’s life actually better? Ben is fascinated by Yong-su even jealous of him. In a world without women, can they find common ground? Maybe three isn’t a crowd. Ben clearly ignites something in Yong-su that can only be extinguished in a literally chilling denouement that should surprise most viewers.

Burning is the kind of textured emotional landscape that makes it a suitable contender for South Korea to get an Oscar nomination in the foreign film category. The depiction of disaffected youth from all socioeconomic factors struggling to find meaning in life and connect with each other should be avoided by all costs by anyone who hates ambiguous endings, but I loved Chang-dong Lee’s most recent film, Poetry, and I’m thrilled by his latest entry.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.