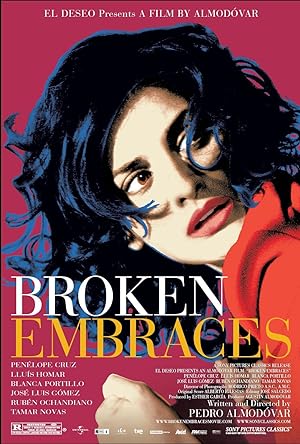

Pedro Almodovar is one of the greatest living film directors, the rightful heir to Hitchcock’s throne with his mix of psychosexual driven dramas and an innovative storyteller who delivers uniquely crafted narratives. When Hulu notified me that his films were going to expire and be removed on June 20, 2017, I decided to watch all his films, including the ones that I already saw. This review is the sixth in a summer series that reflect on his films and contains spoilers.

Broken Embraces is an unsung, should have been sufficiently mainstream enough to become a masterpiece. It answers the question posed early in All About My Mother, “Would you sell yourself to help someone you love?” then pulls a Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge for movies instead of a musical spectacular spectacular with a remixed Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown at its fictional center as the creative baby. Almodovar takes his innovative narrative gifts from Bad Education to subvert tropes such as the high-class call girl torn between others’ security and love. If you aren’t familiar with Almodovar’s work, you may not know that he directed this film because he makes his character proxy, the main creative character, a heterosexual man in a heterosexual relationship, there are no trans characters, and the only gay characters are either stereotypes or villain adjacent.

Broken Embraces is about a blind film director who makes a living by writing scripts with the help of his former producer and her son. When he reads the obituary of a wealthy, notorious man, it stirs up memories and faces from the past, which allows the producer and director to reveal the past to the son and move forward together. Almodovar films usually begin with creation and disorientation so viewers must ask how the opening scene fits into the context of the rest of the film. Unlike his other films, it is obvious that it is a screen test so it is both real and fiction within the context of this film, but the main question is when it is and how is it relevant to the main characters.

Broken Embraces becomes a time machine. We are propelled into the past to see different characters’ point of view during the same period by following the internal thought logic of the story whether it is sparked by reading an obituary to delve into the character mentioned in the news article to see the perspective of the deceased character or if it is the answer to a question posed by a living character to another living character. One character’s memories, which are technically fictional, are treated as bedtime stories. Unlike All About My Mother, on her son’s birthday, the mother tells her son and his father everything at the same time instead of keeping them separated and only revealing the truth when there is no possibility for connection, which enables them to redeem the tragic by strengthening an already existing connection, creating a creative baby, reediting and redeeming a final film and their lives.

Broken Embraces plays with everyone having dual natures and living a secret, hidden life. There is the director/writer, the mistress/actress, the obedient son/the rebellious gay man, the producer/lover, the screenwriter/DJ, the powerful man with everything/nothing. Problems arise only when others are resistant to uniting the two. Every actor in an Almodovar film is amazing, but a special shout out needs to go to Blanca Portilla for playing the producer, Judit. Before she revealed her story at the end, I suspected everything the instant that she appeared. The real fiction within the story is the effort to keep these dual identities apart. Real love can only be achieved when you see and reject what is false, “Don’t smile. The wig is fake enough.” Until Almodovar’s characters are willing to reject an imagined love, they will always remain fractured and shrouded by death.

Broken Embraces has one obvious madman, the possessive and abusive tycoon, but there are others who are equally as violent and driven mad by love, but restrict their hostility to the psychological instead of the physical realm. Judit is a jealous former lover who destroys their creative baby to save an actual one. Ray X is explicitly equated with Peeping Tom, but while tasked to follow his father’s mistress, is actually more obsessed with the director, connecting with his father and finding his identity. Technically the director and the actress are madly and mutually in love so they abandon all caution and self-preservation to be together. The obsessive, all consuming “love” triangle as featured in Law of Desire and Bad Education also appears in this film between Judit, the actress and the director (to win the director’s favor); Judit, the director and the tycoon (to achieve dominance over the film); Ray X, the actress and the director (to get the director’s attention) and Ray X, the actress and the tycoon (to get the tycoon’s approval). The artist’s life is always turbulent that attracts attention whether wanted or not.

Drugs and the medical profession play an important role in Broken Embraces. Without drugs, which are used to financially survive and fully function, the full story would never be told. As in Talk To Her, the medical profession fails to protect or save the majority of the characters from dangerous situations. Instead only a film producer stands between danger and the characters. The medical profession instead becomes an exploitation tool wielded by the tycoon to get characters to do what he wants. Vampires may be marketable, but in real life, they are the devil ready to make a Faustian deal with vulnerable and desperate women. What was odd about this film was how the penultimate crash scene is simply an accident and not a jealous assassination attempt by the tycoon. Did Almodovar think it was too contrived? It felt like a pulled punch after the push. The only person consistently saved is the son.

Broken Embraces is also emblematic of Almodovar’s fascination with missed connection and miscommunication, specifically a character listening to a message as it is being left by another character and deciding whether or not to answer. Missed connections may result in a lifetime of misery for the characters, but it adds texture and another fork in the narrative road, which results in increased pleasure and revelation for the viewers.

Broken Embraces harkens back to Almodovar’s earlier work, Tie Me Up! Time Me Down!, by tackling the idea of a director’s final film and his obsession with the leading lady, but instead of making him an impotent old man with thwarted desires, he makes him unaware of his fate, the loss of his eyes and his love. There are repeated allusions to Antononi’s Blow Up with the idea that the photographer sees less than what is captured on film. As in Bad Education and original The Housemaid, the director/writer gets inspiration for his movies from newspaper stories. There is an explicit visual reference to Voyage to Italy, but instead of being encased in volcanic ash, our lovers are memorialized by Ray X’s film. I’m sure someone could write a thesis by comparing and contrasting the changes of the original Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown versus Girls and Suitcases: terrorists vs. drug dealers, a young model vs. a councilor of social affairs, and a psychologically fragile protagonist vs. a physically disabled protagonist, one of the actors in both versions plays different roles-a sleeping fiancé vs. crazy mother. There are echoes of Hitchcock’s Notorious in this film.

The most poignant and powerfully emotional scene in Broken Embraces is when the writer and producer’s son walk down the steps together. Even in the face of tragedy and death, everything beautiful does not die, and the seeds for redemption, reconciliation and rebirth exist. There is no defeat as long as the story survives.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.