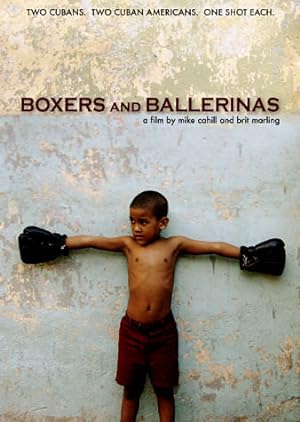

I am a fan of Brit Marling and Mike Cahill’s films, which is the only reason that Boxers and Ballerinas ended up in my queue. It is the first film that they directed together followed by feature films such as Another Earth and I Origins, which they wrote together, but only Cahill directed. Marling also struck out on her own or collaborated with others when she wrote and acted in Sound of My Voice and The East, two films that I enjoyed. I have not been as devoted to following Cahill’s career after their split It is probably for the best that they stopped at I Origins, which is not their best individual or collaborative effort, but was not enough to deter me from seeing how the magic began. Honestly the documentary could have been about anything, but I still would have watched it.

Thanks to Michael Moore, when people think of Cuba, we think of socialized medicine with lust in our hearts, day dreaming about what it would be like to prevent yourself from dying without being crippled by debt, but before that, as Americans, we thought about the horrible dictator, Fidel Castro, and people fleeing the island communist country for Miami. Cuba was well known for cigars, Desi Arnaz and many talented athletes. So the concept behind Boxers and Ballerinas is kind of brilliant. Choose one boxer and ballerina, two gendered professions, from each nation, Cuba and USA, then document their lives to let the viewer decide whose life is actually free, which is what attracted my mom to the movie.

Boxers and Ballerinas is not a conventional documentary. It is an observational documentary with poetic elements. The images rarely match the audio, and while there is a loosely structured narrative, it is not obvious to the casual observer. Even though talking heads expound on the definition of freedom, they never appear on screen. The camera angles were rarely straight on because some of their filming was done surreptitiously. Marling and Cahill dubbed their style “homemade, guerrilla style filmmaking.” I could see detractors deriding this style as endemic to first time filmmakers doing too much. I have been known to get frustrated with such a surplus of eccentric narrative styles, but it worked for me. If a movie isn’t linear, it could lose mom and leave her confused, but she could not stop raving about it and loved it. It is rare for both of us to agree on the quality of a movie, especially since we have such a different range of tastes and movie experiences.

Boxers and Ballerinas is not the kind of documentary that you can multitask while watching. You have to give it your complete, uninterrupted attention and be prepared for the constant dissonance between the audio and the visuals. The Cuban boxer and ballerina are Yordenis Ugas and Annia Recia, and the American boxer and ballerina are Sergio Garcia and Paula Roque. We gets a bird’s eye view of their lives, but not an extensive summary of their lives up to that point. Ugas probably has the most objective success since you can Google him, but the film gives us no insight into his heart whether out of savviness or natural reticence. We do see his hometown and how he is the equivalent of the town’s famous quarterback. Recia goes on the biggest emotional journey—yearning to travel then eager to return home. We get the coolest extended dance sequence near the end of the eighty-four minute documentary intercut with cock fighting. Two birds who can’t fly fighting each other would be a perfect visual metaphor if the Cuban sequences felt more competitive, which they don’t.

Garcia and Roque are unsurprisingly more frank. Boxers and Ballerinas provides the most background on Roque, and her story will provide attentive viewers with the most reward because when it begins, you may not realize that her story has begun because it begins by focusing on the person that made her life as an American possible. Even though Garcia and Roque are proud to be Americans, it is impossible not to notice that in comparison to their Cuban counterparts, the issue of survival stands in the way of their professional goals. Ugas and Recia may not have much, and their aspirations may have limits, i.e. the ceiling is lower, they are still secure enough to focus on what they love. Roque is painfully aware of this limitation since it raises the question of loyalty and tradition versus the potential for more opportunity and fame. Garcia is far more optimistic and brags about how easy it is to be a success in America….just before his father loses his job.

Boxers and Ballerinas only frustrated me because I had no idea whether or not any of the featured four were objectively good. We find out how Roque stands out of eighty people competing for admission into the Washington Ballet, and Ugas successfully competes internationally, but because I’m unfamiliar with the names in the boxing or ballet world, they could be household names, and I’m clueless. I also did not see enough footage of them dancing or fighting to subjectively decide whether they were doing well. We do see a clip of Recia working internationally, and her work seemed closer to a showgirl than a ballerina. I could be completely wrong since while I enjoy watching dancing, I am no expert, but coupled with her eagerness to return home, I suspect that it was not what she was led to believe.

I highly recommend Boxers and Ballerinas for people interested in either profession, Cuba or Marling and Cahill’s films. Trigger warning: one of the voices in the audio is Presidon’t expressing his desire to build a hotel in Cuba. Ugh. He couldn’t even make the house win at his casino in Atlantic City.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.