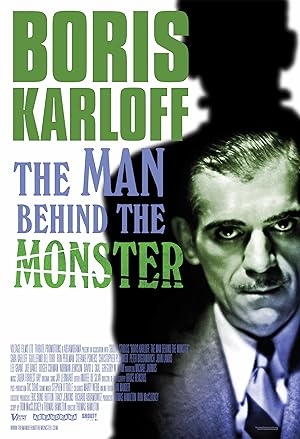

“Boris Karloff: The Man Behind the Monster” (2021) is a ninety-nine minute documentary about the titular actor. Ron MacCloskey, one of the writers and producers of this film, may see this documentary as a sequel to the first film that he wrote and produced, “Karloff and Me” (2006), which parallels Karloff’s life with the writer, who is apparently the largest collector of Karloff and Frankenstein memorabilia. Thomas Hamilton directed, and Paul Ryan, a photographic historian, narrated.

“Boris Karloff: The Man Behind the Monster” consists of film and television clips, montages of archival photographs and interviews. The feature begins with quick references to Karloff’s most famous work. The opening credits consist of a montage of illustrations reminiscent of stills from Karloff’s films and give the film a homemade, amateur feel. These illustrations reappear as virtual backgrounds for some of the interviews. After the credits, the film resumes with his breakthrough role in “The Criminal Code” (1930) before detailing how Karloff got the role and created Frankenstein’s monster. The feature subsequently shows how Karloff became mononymous before delving into his personal history, how he became an actor then summarizing his early film career prior to 1930 through his death, which includes being a union founder of Screen Actors Guild along with fellow monster icon Bela Lugosi, the first onscreen Dracula!

“Boris Karloff: The Man Behind the Monster” is less a biographical documentary than a bunch of talking heads fanboying about Karloff’s work. The talking heads vary in terms of fame. For every moment with famous directors such as Guillermo del Toro and Peter Bogdanovich, famous actors such as Ron Perlman and Christopher Plummer and famous movie reviewers such as Leonard Maltin, the feature also gives you a parade of interviews from less widely known cultural historians, but they are not dispassionate academics. del Toro describes each Karloff film as if it is a religious experience and discusses how “Black Sabbath” (1963) influenced “Cronos” (1993).

If you are looking for details about Karloff’s life, expect to sit through a lot of gushing about Karloff’s movies and wait for his daughter, Sara Karloff, to spill the tea about her daddy, who was of Indian descent and avoided discussing his personal life because of a family history of mental illness, abuse and scandal, which involves his brother being accused of a murder. It is baffling that the film dropped that detail without devoting a few moments to telling the complete story instead of just showing some newspaper clippings. For a man with multiple marriages, the film gives zero Tony Curtis Hollywood Babylon style tabloid dishing. Most of these details seemed tragic rather than nefarious so elaborating would not damage the family’s reputation, but the filmmakers are fans who appear to want to honor Karloff’s private nature.

“Boris Karloff: The Man Behind the Monster” does deliver a portrait of a man who was a passionate actor invested in his career as art more than fame or money. Even work induced injuries and diminishing health could not stop his showmanship. For Karloff, live television was the equivalent of theater, and movies were formulaic, monotonous money makers.

“Boris Karloff: The Man Behind the Monster” is a career retrospective for fans, not critics. I do not mind watching people gush about movies and why they love them, which is why I mostly enjoyed this documentary, but the film assumes that the average viewer is more familiar with Karloff’s career than the average viewer is. Other than any of Karloff’s Frankenstein related films, I am clueless, but receptive so it would have been helpful as they discussed each film to include a sentence about what the film was about instead of assuming that the audience would be able to extrapolate that information from the clip.

Films like “Boris Karloff: The Man Behind the Monster” give viewers an opportunity to learn more about classic films without slogging through a lot of dreck and wasting time. If you see a clip that intrigues you, this film helpfully lists in the corner of the screen the title and release date so you can add it to your watchlist. If you love classic horror, but do not know where to begin other than the classics such as “Dracula” (1931) or “Frankenstein” (1931), this film will give you plenty to choose from. I walked away wanting to see “Black Sabbath,” “The Black Cat” (1934), “The Body Snatcher” (1945), which was already in my queue, “Isle of the Dead” (1945), “Bedlam” (1945), “Targets” (1968), which was also already in my queue.

“Boris Karloff: The Man Behind the Monster” does give lip service to Karloff’s racist films. Before the reveal that Karloff is of Southern Asian descent, it shows Karloff in a variety of “Yellow Peril” roles, i.e. racist depictions of East Asian people. The documentary misses an opportunity to briefly examine this longstanding xenophobia against Asian people. The documentary uses audio from an interview in which Karloff responds to whether there was a Chinese advisor on the set of “The Mask of Fu Manchu” (1932), “It was a shambles. It was simply ridiculous.” While the interviewees admit that this film was racist even for that time, they laugh it off and revel in Karloff’s performance. Here is where the lack of diversity of the interviewees, who are mostly white men, undercuts the credibility of the film. For a film that has been conducting interviews since 2018, it is a serious the failure of imagination that it never occurred to the filmmakers to find a single historian who could speak on this issue without bursting into laughter or barely suppressed glee about how bad the film was, but would take it seriously as damaging to real people and has an impact to this day. Did it occur to anyone to ask Karloff’s daughter how he felt since he hid his Asian heritage to gain acceptance yet played such roles? Did such roles validate his decision to hide his ethnicity or feel unrelated since he was not Chinese?

If you are not into movies, you should probably skip “Boris Karloff: The Man Behind the Monster.” I understand beginning the film with “Frankenstein,” but when the film waits until the middle of the film to describe Karloff’s beginnings then move forward, it does feel as if the film is repeating itself although it is covering new ground during a period briefly touched upon earlier in the film. Taking a chronological, traditional approach would have averted that problem. By the end, though I was enjoying it, it began to feel never ending.

Even though Karloff rejected the idea that his films belonged in the horror genre and preferred to call them thrillers or “shock” films, horror fans who do not think that classic horror is boring will want to add this documentary to their queue to brush up on their film history with the caveat that it does feel less like fan boying and more like fan old manning since the majority of the unknown talking heads fit that demographic whereas horror fans today consist of many women and minorities. It is interesting that in order to be taken seriously in opining about popular culture, you still have to fit a certain demographic otherwise expect zero representation.