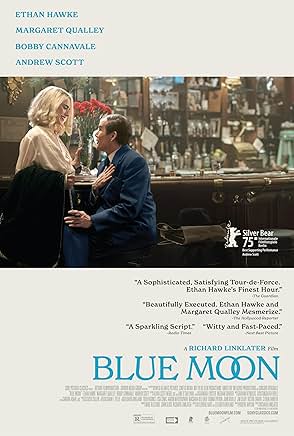

Beginning near the end of lyricist Lorenz Milton Hart’s life, on November 17, 1943, on a rainy night in an alley with a radio broadcast obit playing over it, “Blue Moon” (2025) rewinds to March 31, 1943, seven months earlier, on the opening night of “Oklahoma!” mostly at the Sardi’s after party, to implicitly understand the causes of Hart’s death. Recognizing that everyone has left him behind or only care about him out of a sense of obligation or for what he can do for them, Lorenz (Ethan Hawke) drinks and talks to stave off the inevitable fading into the background and does his best to stay center stage. Writer and lifetime New Jersey resident Robert Kaplow adapted the story from Hart’s correspondence, which Kaplow bought at an estate sale. If you are alert and enjoy fast-paced dialogue with plenty of cultural references, you will enjoy director Richard Linklater’s latest film, but if you are even a little tired, it will only come alive once the writer E. B. White (Patrick Kennedy) and composer Richard Rodgers (Andrew Scott) talk with Lorenz.

Could “Blue Moon” work as a play over a movie? Not as a price point or for the sake of realism, but yes. From the opening scene, it felt like a very nice set, but a set nonetheless. The aesthetic of the era is captured seamlessly except when Elizabeth mentions drinking legal age. Linklater’s style usually feels more open air and lived in. Cinematographer Shane F. Kelly gives the interiors a lived-in feel, but the exteriors feel thin. Thanks to the forced perspective made famous in the “Lord of the Rings” franchise and a hair stylist creating a bald patch, almost six-foot Texan Gentile Hawke plays the foot shorter first generation American Jewish New Yorker, closeted artist as a flamboyant “ambisexual” man. Hawke really throws himself into the role and completely disappears. He resembles a smaller version of John Malkovich; however, his gravelly voice is impossible to disguise.

Hawke plays Hart the way that Kaplow wrote. It is fun to watch Hawke chew the scenery and talk everyone to death. Still, it was not enough to suspend disbelief over the story of Lorenz setting his heart on twenty-year-old Yale college student, Elizabeth Weiland (Margaret Qualley). Elizabeth is a complete work of fiction, but Hart did know a woman with the same name, and oh, if only she is alive or her family connects the dots so we can know more about her. Everyone loves Qualley, but it is her usual schtick: a beautiful, clever woman. If fully closeted, chatting about some girl makes sense, but here, it verges on tiresome. Within the story, Lorenz advises George Roy Hill (David Rawle) to focus on stories about friendships, “Be careful of love stories. Think about friendship stories. That is where the really enduring stuff lives.” It is advice that Kaplow should have taken.

I do not know nearly enough about Hart’s life to fact check the movie, but ever since “The Shape of Water” (2017), I tend to get suspicious of straight people framing a gay man as a tragic, lonely character, and in “Blue Moon,” it is additionally implied that it is because of Hart’s looks and sexuality as much as his alcoholism. Is that fair? Maybe. Maybe not. The whole story is fiction, but have you met short kings or unattractive men? They generally do not remark on it and seem as confident as a super model so if there is insecurity, it is deep, not on the surface. I’ve seen women pay thousands to bail a man out that most would not touch, and these men did not have a good personality or money. Men have been snagging women out of their league ever since they lost a rib, and add talent and money, Hart could be beating women away with a stick. Lorenz feels like a taller, more attractive man’s concept of what it must feel like to be a short, Jewish, gay man, not a real short, Jewish, gay man. For fun, I started googling actors who are four feet ten inches tall like the real-life Hart: Danny DeVito. Leslie Jordan was four feet eleven inches. I am too literal minded, but to buy Lorenz’s fictional sorrow origin story, I had to forget everything that I knew before, and it never happened. Anyone can make a movie about anything, and it is not an exhaustive, comprehensive biopic, but if it was, one factor that would be required is the effect of Hart’s mother death in April, his second heartbreak.

The real reason to see “Blue Moon”: Andrew Scott. He makes Richard Rodgers real and plays the full range of emotions. By playing memorable villains, Scott made himself famous, and he injects a lot of that into his character but is also relatable. Lorenz is clinging to his professional partnership to Rodgers and calls his former collaborator Dick for many reasons. Richard is a cold man because he is protecting himself from getting sucked into the dysfunction of his friend, whom Richard calls Larry. Kaplow writes him as a man asserting his independence and creative vision from the gravitational pull of such a strong personality. Without going big, Scott plays Rodgers’ frustration over seeing a man that he admires destroying himself and knowing that he cannot help him. Once Rodgers’ success is more secure, and he does not have to steel himself against any professional securities by pretending to be more confident than he is, Scott becomes warmer. Scott is so good and seems so effortless that even though Rodgers is only a supporting character, “Blue Moon” feels more alive because of his performance. Scott makes Rodgers seem like a human being existing whereas everyone else in the cast sounds as if they are in a play and aiming for the cheap seats. If that working relationship was compared to a marriage, Rodgers was the wife who begged for her husband to change before filing a divorce then got a glow up. When Larry rejects Rodgers offer to help him recover, it felt as if it was the movie’s natural ending.

Instead, the last act of “Blue Moon” consists of Elizabeth dishing to Lorenz about her lover, and Kaplow may have missed the mark. It felt as if Lorenz was living vicariously through her so if that was the intention, it worked. Otherwise, these scenes feel redundant. Ellizabeth is just another person using Lorenz to meet Rodgers after the pianist, Morty Rifkin (Jonah Lees), a stranger who never does. Booooooo! Elizabeth’s mom is apparently some mover and shaker in the theater world, “The Guild,” so again it felt like the hurly burly evening of the evening was extraneous when the emphasis would have been better put on Elizabeth not understanding people’s true intentions and recalibrating once Lorenz pulls away the veil. “I don’t deserve a friendship like yours.” Again, the friendship angle feels more urgent, especially the uneven playing field in terms of attention and effort.

Everyone wants to play the queer underdog until it is time to be queer. If the first act was shorter, the end could have devoted time to seeing Lorenz charm a man. The ambisexual needed more bi and sexual, not just gay affectation. “Blue Moon” feels incomplete as a story about a man, but as a story of an artist approaching his twilight, it works. It is the connecting point that these three long term collaborators, Linklater, Kaplow and Hawke would relate to, but real creativity feels like Scott’s portrait of Rodgers, seeing a complete person in a snapshot.