This review was originally published on Roarfeminist.org

“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser gate. All those moments will be lost in time…like tears in rain…Time to die.”-Roy Blatty, January 8, 2016, date of birth, November 2019, date of death.

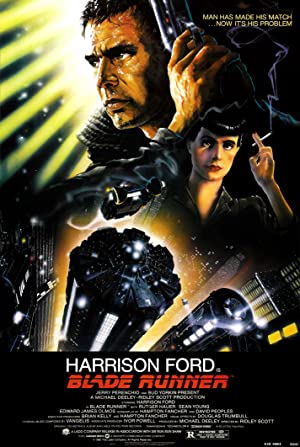

Blade Runner is simply one of the greatest films ever made. There is not a film or television show that is not in some way influenced by its dystopian vision of the future: a polluted, dying world run by one powerful corporation that equates luxury with enslavement of those who are actually superior to them in terms of empathy and the ability to understand the difference between right and wrong. From such horror shows as Ghost in the Shellto such recent hits as It, from its cityscapes to its performances, Ridley Scott’s creation has spawned numerous ripoffs or tributes. For instance, compare Daryl Hannah’s performance to Bill Skarsgard’s scary clown and the similarities arxe eerily similar if you are familiar with both story lines. No flying cars though, which is probably for the best.

If you want to understand Ridley Scott, you have to start with Blade Runner. When you first watch the film, you may think that Harrison Ford, whose profession is the title of the film, is the hero of the film, a special type of police detective, especially if you listen to what all the authority figures such as Tyrell and the police chief say. Replicants are described as machines gone wrong. Deckard is terrified of Rachel, and the film does seem to eye her suspiciously throughout the film. They kill human beings. They are stronger than us. They are not supposed to be here. At times, particularly when Roy confronts his maker and is surrounded by candlelight, the upturned collar of his coat is reminiscent of Dracula. We see them brutally and repeatedly kill human beings. They act strangely: their cadence, their physicality, their motives.

If you really pay attention to Blade Runner, your sympathy will ultimately shift to the replicants. Deckard is not actually good at his job. He is only successful at shooting female replicants, one in the back, which is not even a little heroic and especially after Walter Scott, cannot be reframed in any other way than callous. Roy mocks him for shooting unarmed people, “I thought you were supposed to be good. Aren’t you the good man?” He is rapey, possibly taking advantage of a female replicant’s programming to be obedient. It is more than a little uncomfortable when he looks for her with a gun casually pointed next to her head. Tyrell takes one of his beloved creations and subjects her to cruel emotional abuse without a second thought. When people say a servant is like family, think of how easily Rachel is discarded not because she poses a threat, but because of her difference and her awareness of that difference, which is solely Tyrell’s fault. Even Sebastian and Chew, who appear helpless and benevolent, are proud and seek sympathy for their role in creating the replicants, but take no responsibility for what happened to them thereafter. Roy responds, “If only you could see what I’ve seen with YOUR eyes.” The human beings are the real threats. They take a perverse pleasure in dehumanizing replicants while wanting to make them in their image. The ones in the colonies are proud slaveholders, and the ones still on Earth proudly uphold that system without enjoying the benefits of being a slaveholder. Tyrell is the strangest of all-why does he choose to live alone on a dying world?

Replicants are trained to be slaves to either kill or be raped at the whims of their owners. They can last longer, but human beings purposely design this generation to die at an early age to prevent them from becoming fully human, i.e. emotionally mature, which is delusional considering what we know about them. They love each other, form relationships, display more intelligence than even their creator, who is a genius. After they stage an Amistad-like revolt, they are hunted for daring to return home and ask for more life instead of being treated like toys, objects or creations who solely exist for their creators’ amusement. They kill in self-defense or out of revenge.

Blade Runner is the parallel story of Deckard and Roy, which really emerges in the last half hour, particularly in their romantic relationships. I have always imagined that the revolt began once Roy and Pris developed feelings for each other. They have no desire to imitate their human counterparts and revel in their difference: appearance, inflection, movement, facial expressions. Because Rachel and (arguably) Deckard think that they are human beings, they are programmed either literally or by society to hate who they are or could be, do not hesitate to kill replicants, and their actual relationship is more problematic than Roy and Pris. During the final chase scene, Roy puts Deckard through empathy training: chasing him to make him realize what it feels like to be hunted by people like Deckard; making him feel the pain in his hand by breaking Deckard’s fingers because since the beginning of the film, Roy’s hand has been seizing up; feeling the proximity of death by allowing him to lose his grip and ultimately realizing that his woman will die soon. Roy exclaims, “Quite an experience to live in fear, isn’t it? That’s what it is to be a slave.” Even if Deckard is a human being, he realizes that the difference between Roy and himself are not as much as he initially believed. Death is coming for us all.

Ultimately Scott is angry with God because one day, Scott will die, and he is furious that all his genius will be lost. This obsession with confronting his creator and demanding more life from the Father/the fucker has only become more apparent with his Alien prequels, especially now that the dearly departed Dan O’Bannon is no longer around to ground the franchise. If eyes are the windows of the soul, Roy is Scott’s fictional, cinematic on-screen equivalent as he destroys the soul of his callous creator. Roy taunts, “Fiery the angels fell. Deep thunder rolled around their shoulders burning with the fires of orc.” Roy literally fell to Earth when he descended from the space colonies, a sci-fi Lucifer revolting against the tyranny of a casually cruel creator who cares little for their well-being and has no respect for their innate worth and value as living beings, not simply creations lesser than the creator. Unlike the Bible, in Scott’s world, Lucifer wins, and God is not in the heavens, but in a pyramid already entombed like a god in life and ultimately in death. The rebel will not be mollified with “Well done my good and faithful servant.” An eye for an eye.

There is so much more that can be explored so see or rewatch Blade Runner. My favorite version is the Director’s Cut without the narration. Side note: when Bryant tells Deckard that the replicants escaped, there are three men and three woman. We know that one man is killed before he escaped. Who is the third woman? It is not Rachel. Maybe we’ll find out soon.