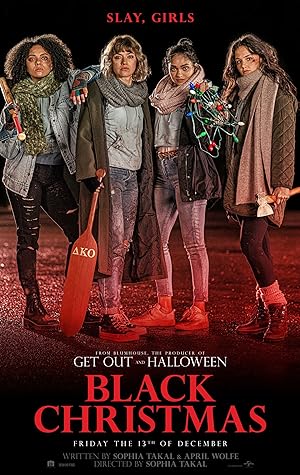

Black Christmas is set on Hawthorne College’s campus right before and during Christmas break as sorors are getting hostile messages from an account sporting the college founder’s name then disappearing. One soror is determined to get to the bottom of it because she already had suspicions about a frat house. Sophia Takal directed it, and Imogen Poots plays the protagonist, Riley.

Takal’s Black Christmas is apparently the second remake of a 1974 horror film so it is the third of its name, and now I have to go down the rabbit hole and watch the other two. I’m unfamiliar with the original film or the remake so I judged this film entirely on its merits. I was interested in this film because I do enjoy holiday themed movies if they strike a discordant tone with the holiday, and a horror Christmas film sounds delicious. Blumhouse Productions are generally my favorite horror house because they are superb at fully utilizing horror to get people to meditate on sociopolitical issues, and the previews for this movie had an overt feminist tilt. I also enjoy financially supporting women directors so even though I am unfamiliar with Takal’s work, I was willing to take a chance on a woman directing horror films, especially during a slow movie week. When I noticed that the showings were going to plummet during the second week, I decided to prioritize it and see it in theaters.

I saw Takal’s Black Christmas as a matinee, and while I did not feel disappointed or angry that I paid to see the movie, I did not get to give the movie as much love as I wanted to give. The story does not quite work once you reach the end then start thinking about the details. The editing of a lot of scenes needed a continuity editor. Takal’s sociopolitical message is so explicit and at the forefront that unlike most horror films, there is not enough room for the viewer to notice and pull out deeper meaning. Takal does not completely trust the viewers to get it so it feels more as if it was ripped from the headlines, and while the horror storyline is related to the meaning, it feels incidental and like an afterthought instead of the best genre to tell this story. It could have also worked as an action movie or a thriller.

The root of Takal’s Black Christmas’ horror story is the supernatural, but it is not well thought out or supernatural enough. It borrows a lot of elements from John Carpenter’s Halloween, but does not quite understand what makes that masterpiece so disturbing. While I appreciate that Takal is trying to make a story that shows how destructive and misogynistic patriarchal power is and use the sororities as a way to show solidarity in sisterhood to fight that power, the movie never seems to understand that power or fully depict how pervasive it is using the horror genre as a tool. The actual depiction of power feels lackluster and unconvincing, and the conspiracy not necessarily as sweeping as it needs to be. I felt that a god should have been explicitly referenced to make the threat seem more sweeping. By the end, it did not even feel as if it could have theoretically had the reach of the Skulls & Bones Society.

Takal’s Black Christmas explicitly addresses the epidemic of rape on college campuses, and in contrast to a documentary like The Hunting Ground, it starts with that heightened awareness and fear then isolates the problem to a specific fraternity whereas the documentary is more terrifying because it shows how every element of campus society contributes to the real life horror without the students even knowing that they are in a horror movie. The villain in this film is obvious, and no offense to Cary Elwes and his colleagues, but not that memorable or impressive. When I did not fully understand the supernatural aspect, I was hoping that it was going to draw on how omnipresent on campus that corrupted power was, how it was triggered to protect itself and how it manifested in various locations, but the actual reveal is less interesting and does not actually explain the first two murder scenes because the killer seems to be able to disappear and reappear in areas where he was not before. I liked that the men were also victims of patriarchy, but it felt as if the movie did not fully elaborate on exploring the full range of culpability, from privilege to complicit to actively reinforcing.

For Takal’s Black Christmas to work, choosing a single protagonist to empathize with rather than making the film more of an ensemble that covers the whole campus was probably a mistake. There is a theme of ants, power in numbers and more strength than appearances would indicate, that is supposed to counter the fraternity, but just like the fraternal brothers are blandly sinister, the sorors, though way more interesting, mostly have an interchangeable feel except for Riley’s two closest friends, Kris and Marty. For the denouement to really pop, it felt like there needed to be more of a gradual build up so that we could notice how a weapon or fighting technique really suited that particular sister and root for her. Instead all we have is Riley and her infliction of violence is not cathartic enough.

Takal’s Black Christmas wisely uses certain weapons familiar to women or imbued with narrative significance to fight, but I am disappointed that the shovel kind of went nowhere nor was it the best kind of shovel to use. It should have been one with a metal scoop instead of a plastic one. Instead it was just vaguely hilarious instead of menacing then it was a dangling thread. Also it should have been a consistent narrative point that when anyone not down with the patriarchy tried to use traditional weapons, it did not work, but women’s weapons would be the only effective tool.

Takal’s Black Christmas also had a Patricia Arquette 2015 Oscars’ speech feel where initially as a viewer, folks are cheering her on, then she goes in the back to do press and says “we fought for you, now you fight for us,” and seconds later, the viewers channel their inner Tyra Banks, “We were rooting for you.” When you are a fish, you do not realize that you are swimming in water, but Takal’s brand of feminism is trying to be intersectional while making the same well-intentioned all thumbs mistakes that Arquette did. Takal gets it in the way that she shows how two women, a fifty-two percenter and a forty-eight percenter who likes to entertain the fifty-two percent are most vulnerable whereas the black girl figures out the threat, but Riley inadvertently becomes the Arquette figure that deflated a scene which should have felt like a “This is Sparta” rallying cry moment.

Also I know that Blumhouse Productions probably does not have Twitter or Facebook Messenger money for Takal’s Black Christmas, but the Yip Yap app did not quite work for me. I wish that there was just a casual line of dialogue about how lame it was that the college used its own app, and each student had to belong to it in order to sign up for classes, services, etc. as part of enrollment which explains why it did not have certain features to block a hostile sender so the founder WAS actually sending the messages.

Takal’s Black Christmas is an entertaining diversion, but it loses its luster when held up to examination, and the horror was not as well thought out as the message, but the message could be just as clueless and endemic of the power structure that it sought to critique. I had a good time, but I was hoping for a great one. Maybe next time.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.