I love old Hollywood movies, and young Charlton Heston was hot so of course I saw the 1959 version of Ben-Hur. I already expected that Timur Bekmambetov’s Ben-Hur would not be as good as 1959 Ben-Hur, but I prefer to live in a world where Bekmambetov can get funding to make films so I decided to see it in the theater.

Ben-Hur is third adaptation of a book, which I have not read. Childhood friends, a Jewish nobleman and a Roman orphan, grow up to become enemies. The Jewish nobleman who was formerly a moderate-someone who was not a violent Zealot against Roman occupation, but also unwilling to completely capitulate to Roman rule, finds himself understandably wanting revenge in a world where revenge is against the law since Rome is the law; thus, the chariot race is his only feasible option. Add an occasional dash of Jesus to suggest another way to resolve the conflict. Which way will prevail?

I am really glad that I saw Ben-Hur in theaters because I got to gauge other viewers’ reactions. Is it normal for audiences to disapprove of Ben-Hur violently lashing out at Romans? Bekmambetov’s Ben-Hur succeeds in ways that his producers, which include Trump supporter, Simon Burnett, and his wife, Roma Downey, who previously worked on such TV miniseries as The Bible, Son of God and A.D.: The Bible Continues, which is the best of all their work, probably did not intend. Bekmambetov’s Ben-Hur parallels America/formerly USSR, now Russia with the Roman Empire and uses the imagery of cop brutality against unarmed, law-abiding citizens to condemn both America’s/Russian foreign policy and any local law enforcement that does not get punished for excessive use of force. Bekmambetov’s Ben-Hur made audiences uncomfortable unlike films like The Hunger Games or Star Wars franchises, where the viewers were able to root for the scrappy underdog using violence in the theater then turn a blind eye to injustice in the streets and castigate peaceful protestors.

Bekmambetov’s Ben-Hur radical approach to the work does not end at eliciting anger from his audience, but he further angers by departing from 1956 Ben-Hur’s vengeful model. Bekmambetov’s Ben-Hur explains that it is rational and just to strike out against the Roman Empire by participating in the chariot race-radicalization of formerly moderate forces is a rational response to state violence. He depicts why all Ben-Hur’s competitors also want to legally beat Rome’s ass, and it has nothing to do with sportsmanship or lofty Olympic dreams. When Ben-Hur wins, he shows that while there is a symbolic victory against Rome, but ultimately only the individual, not the Roman Empire, is wounded. So if every strike against Rome only makes more victims and does not destroy Rome, but enforces and recreates Roman values, how can you win? JESUS!

“They are all Romans.” By participating in the Roman power structure and their rules, even those who are enemies of Rome become Rome by using the hegemonic power of Rome. Cue Snowpiercer-we need to destroy the system, not the people who are a part of the system. The Roman soldier must abandon his post, his allegiance to Rome over his allegiance to love and stop seeking the privileges accorded to a Roman soldier. Through radical forgiveness and reconciliation on both sides and a willingness to opt out of that system, the possibility of living like children in the kingdom of God instead of like warring adults in the empire of Rome becomes a reality and creates a neutral, mental space that does not erase history, but transcends it.

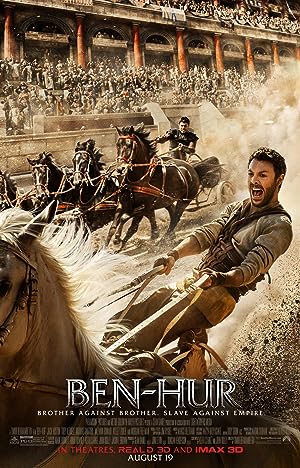

While Bekmambetov’s Ben-Hur is a philosophical treatise and delight, it is not necessarily a solid film. Bekmambetov’s Ben-Hur begins with the “how we got here” narrative technique by opening with a clip from the chariot race, which should always be the climax of the film. Why is the Greek guy blonde? I have a weakness for Jack Huston since Boardwalk Empire, but he is no beefcake Charlton Heston. The best action scene is not the chariot race, but the ship battle when Ben-Hur is a slave. Bekmambetov’s Ben-Hur does not have any of his trademark film flourishes like Night Watch, Day Watch, Wanted or even Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Hunter, which is disappointing. As the seeming successor to the Wachowski sisters, Bekmambetov’s Ben-Hur is a lackluster entry in his body of work.

While Bekmambetov’s Ben-Hur may lack visual verve, I still give him an A for effort as a Russian director interpreting American popular culture and challenging America mythology and white evangelical concept of Christianity as enforcing instead of challenging the status quo.