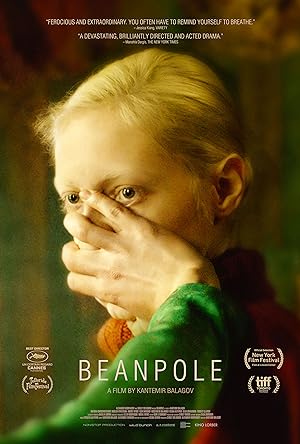

I considered seeing Beanpole in theaters after its opening week because it lasted another week and came to a theater closer to me. I enjoy Russian films, studied World War II and the Battle of Leningrad and am interested in movies about women vets, which are rare, but I was slightly reluctant to see this particular film because the summary was too vague, and it is two hours ten minutes long. Also it had considerable competition so I did not prioritize seeing it. It was only in theaters for two weeks because the pandemic forced theaters to shut down. I got it from Netflix as soon as it became available on DVD, but it has taken months to actually get around to watching it. While it is a beautifully crafted film, I am glad that I did not see it in theaters.

Beanpole is the titular nickname of one of the main characters, Iya. The movie is set in Leningrad, the first fall after the war. (So the war ended during the fall of 1945 so does the film mean that year or the subsequent year’s fall? I am overthinking it.) Eleven minutes pass before we meet the character who provides the real momentum of the movie, Beanpole’s war buddy, and the movie’s main character in my opinion though Iya is a perfect foil for her. Initially the movie really grabbed my attention by gradually revealing details about the characters, and each revelation somehow made an already sad situation worse. We hear her war buddy before we see her, and it takes a long time before we even learn her name, which is why I am reluctant to state it here. The film’s ability to turn the screw is impressive. As we hear more stories about her life, it is hard to figure out what is real and what is fiction. The movie is not just about the two women, but also the people in their orbit.

Beanpole is about how impossible it is for broken characters to return to “peaceful life.” It is literally impossible. Everyone is broken in some fundamental way, and their idea of life outside of war is warped. It felt less as if the solutions to return to normalcy was post World War II than Biblically Old Testament. Did I also discern an Anna Karenina reference, but instead of a train, it was a streetcar? People do spectacularly cruel things to each other, but the characters react to those acts as if they were the equivalent of being blunt and often does not diminish the affection that characters have for each other. In any other context, such behavior would hopefully be a relationship dealbreaker. War has irreparably damaged them. Even if the movie’s story bears zero resemblance to real life, I understand why Balagov would feel that this story would work in this setting because without it, these characters would be sociopaths and unsympathetic. Instead they have the mentality of children in adult bodies.

As Beanpole unfolds, it gradually becomes more sensational in the ways that the film depicts post war life. I preferred the earlier moments which felt more organic and subtle such as our initial introduction to Iya, watching people interact in a communal kitchen or seeing patients try to entertain an unexpected visitor. The deliberate pacing and rationing of revelations lose credibility as they accumulate. As the movie continues, it becomes more melodramatic and predictable. There was one scene which would not necessarily be out of place if a Bond villain gave the speech on a low threat day. I love a bleak movie, but gradually the two main characters’ dynamic started to strain my suspension of disbelief, especially when it involved other people. It felt almost Rube Goldbergian, but also I began to spin ways that the story could deteriorate further and am relieved that the film refrained from taking one character’s desires to even more sensational extremes. For instance, the significance of a Christmas celebration was not lost on me. After awhile, it was too heavy handed for my tastes.

The denouement was unexpected and refreshing, but it left me wanting to know more about the matriarch’s story. While her appearance and surroundings are in stark contrast with the majority of Beanpole, her demeanor held a flinty, perspicacious view that indicated a sober confrontation with brutal reality and perhaps she is the only person who left it stronger. She is so clearly in charge regardless of where she is sitting. She left me wanting to know more. What did she do during the Battle?

Visually Beanpole is gorgeous. I enjoyed the counterintuitive composition of the frames, and the occasional claustrophobia of the camera’s proximity to its subject. The significance of the color palette was a bit obvious and heavy handed, but ultimately soared and was vibrantly sumptuous. The tracking long shots of characters moving in large tableaus and not knowing which character was the focus of the shot created a momentum and helped me to get further invested in the supporting characters and their stories. Balagov definitely has an eye and am thrilled that he did not use black and white as originally planned.

After watching Beanpole, I watched the extra feature, an interview with the director, Kantemir Balagov, and a book, Svetlana Alexievich’s War Does Not Have a Woman’s Face (the English translation title is The Unwomanly Face of War: An Oral History of Women in World War II), inspired his story. I briefly read descriptions and excerpts of the book to see if the movie reflected its source, and it does not seem so, but I plan to read the book to judge thoroughly for myself. Not every movie is made for me. I am not Russian. When a movie primarily defines a woman character by her ability to have children, I always have an issue with the movie regardless of its genre. It was disappointing because I feel as if I am more exposed to images of women as defined by their sexuality in war whereas the book created the impression that it was going to address women who were soldiers then flinched and swerved. Sex should play a role, but it is central to the movie. I feel as if I was misled, especially after learning more about the original source. If the movie was more upfront about the story, I probably would have watched the movie anyway, but I would have different expectations. While it would be severely reductive to suggest that it is the only focus of this movie, it is a dominant theme, and for me, the theme of having children is too reductive of a woman’s experience though I appreciate that children would have a greater significance in a postwar world as a symbol of hope for renewal and a new life. I feel as if there was a lack of alignment between how the movie was promoted and what the movie actually was.

I know that Svetlana Alexievich has more to do than watch Beanpole, but I would love to know what she thinks of the way that Balagov used her work as a launching point to create stories that, according to him, express his feminine side. She is not only a Nobel Prize in Literature winner, but she is a kind of political refugee from Belarus after joining the Coordination Council during protests against corrupt elections.

If World War II left people asking who would survive the war then Beanpole asks who will survive the peace?